When oxygen supplies at Shri Ram Singh Hospital in New Delhi ran critically low a week ago, Dr. Gautam Singh, who runs the facility, hit the road at night to plead for oxygen from suppliers and also put out a desperate appeal on social media. Finally, a local official helped secure some cylinders to help alleviate the crisis.

But after the nightmare of ensuring that his patients are not left gasping for oxygen, Singh has drastically cut back on the number of COVID-19 patients he takes into his facility even as the raging second wave of the pandemic has led to an acute shortage of hospital beds in the city.

“We run the same race daily, we have to beg for oxygen but supplies are still very short. It breaks my heart to turn away people, they come in bad shape, but what can I do?” said Singh in a quivering voice.

“We have the beds but not adequate oxygen and the sad part is we can keep only as many patients as we can support on oxygen as that is the only thing that lets us buy time to save them,” he added.

Although his facility has 50 beds for COVID-19 patients, he said he now treats about 12 or 13 patients.

From smaller hospitals like Singh’s to large ones, the desperate battle to ensure sufficient supplies of oxygen needed to treat COVID-19 patients whose oxygen levels run low is now in its second week.

Sometimes they have lost the battle -- patients have died when oxygen stocks ran critically low.

“This is one of the biggest tragedies I have seen in my life. Patients are dying because we don’t have oxygen,” S.C. L. Gupta, medical director of Batra Hospital in New Delhi told local television channels after 12 patients died on Saturday, when delivery of the lifesaving gas was delayed by 90 minutes. It is one of the city’s most prestigious hospitals.

Some worried hospitals have asked families of patients to bring back-up supplies of oxygen. Ordinary citizens have been running from pillar to post, often standing in lines for hours and sending out urgent pleas to friends and family to get a portable cylinder. People are rotating supplies – those who recover lend oxygen concentrators and cylinders to others in need. Volunteer groups are pitching in by trying to refill empty cylinders at oxygen plants.

The Indian capital is not the only one facing an oxygen crisis – scarcities have also hit other cities and smaller towns as the second wave spreads deeper into the country.

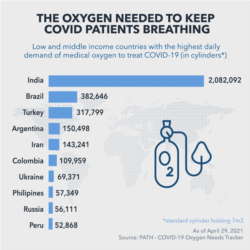

Demand for medical oxygen has spiked significantly amid the second wave in which numbers of daily infections are more than three times the cases reported at the peak of the country’s first wave.

The federal government denies reports of shortages and says the bottleneck is due to transportation from key production centers that lie in eastern and southern India to the worst affected parts of the country.

"There is enough oxygen available in the country," Lav Agarwal, a Health Ministry spokesman, said at a press conference on Monday.

The government is using “oxygen express” trains to transport the lifesaving gas to some of the worst-hit parts of the country – two such trains arrived in New Delhi on Wednesday according to Railway Minister Piyush Goyal. Officials say India has ramped up oxygen production and diverted all industrial oxygen for medical use. Two oxygen plants have also been installed at two of the largest government hospitals in New Delhi.

But the situation on the ground continues to be grim and health experts say surging cases of COVID-19 could only exacerbate the crisis – on Thursday India reported its highest tally of 412, 262 cases so far.

Courts have stepped in to direct the government to address the oxygen crisis -- the Supreme Court has told the federal government to ensure that the capital city gets its full quota of 700 tons of oxygen and asked how it plans to deal with a third wave, which scientists have said is “inevitable.”

Some judges have made strong comments -- on Tuesday, the Delhi High Court that has been hearing urgent appeals by hospitals wanting oxygen told officials, "You can put your head in sand like an ostrich. We will not," and asked “Are you living in ivory towers?”

On the same day a high court in Uttar Pradesh, one of the worst affected states in North India, said that "death of COVID-19 patients just for non-supplying of oxygen to the hospitals is a criminal act and not less than a genocide by those who have been entrusted the task to ensure continuous procurement and supply chain of the liquid medical oxygen."

Public health experts blame the situation on a lack of sufficient planning and complacency that the country would not be hit by a second wave after cases in a first wave were brought down to less than 15,000 earlier this year.

“Some of these challenges were identified but not followed through after the first wave of the pandemic began to subside,” points out Chandrakant Lahariya, a public policy and health expert in New Delhi. “For example, plans were made to set up oxygen generation plants in 160 districts but most of those have not come up. The standard approach is that when the crisis is at hand you identify the problem, but soon after it is forgotten.”

The government announced last month it will set up 500 oxygen production plants across the country.

For doctors like Singh, it is a hard time but he is not giving up the fight. “Patients are going from door to door desperate for help. Hopefully we will again be able to serve more people as soon as supplies stabilize. Officials say the situation will improve,” he said.