But South Africa then was even more deeply divided along racial lines than it is now. It was also split along sporting lines, with the white minority being passionate followers of rugby, and the black majority worshipping football, otherwise known as soccer.

In most parts of black South Africa, the country’s rugby team, the Springboks, was reviled as a symbol of racial oppression. The Springboks had been funded and adored by successive administrations of the National Party (NP) - the largely Afrikaner political organization that established apartheid in 1948.

But the Springbok captain in 1995, Francois Pienaar, was convinced that winning the Cup could help reconcile black and white South Africans.

The burly blonde Afrikaner wasn’t alone. He found a powerful ally in then-President Nelson Mandela – the revolutionary leader of the African National Congress (ANC) who had been jailed for 27 years by the NP government for fighting against the white supremacist regime.

Pienaar and Mandela formed an unlikely and dramatic partnership that sustained a nation at a particularly fragile time in South Africa’s often tragic history.

The former Springbok captain recalls Mandela phoning him constantly during the 1995 World Cup, asking after the team’s well-being. During the competition, the president also appeared on national TV to assure the Springboks of his support.

Pienaar says Mandela’s backing “meant the world” to him and his team of underdogs. Rugby pundits had written off their chances of winning the trophy, but the Springboks eventually battled through to the final. Their opponents were the New Zealand All Blacks, who at the time were the mightiest force in international rugby. Again, the experts maintained South Africa had no chance of victory.

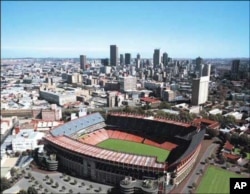

But Mandela disagreed with them, and in the dressing room of the Ellis Park Stadium in Johannesburg, a few hours before kickoff, he told Pienaar so.

“Madiba stood there, wearing a Springbok jersey; he had a Springbok badge over his heart. It was very emotional for me, seeing this man, who had gone through so much, being willing to do this for us,” he recalls.

To this day, Pienaar refers to Mandela affectionately by the liberation hero’s Xhosa clan name, “Madiba.” Yet the rugby player, like most white South African children of his generation and before, had grown up fearing Mandela as a “terrorist.” But, in the space of a few weeks, Pienaar and his team containing just a single black player had come to know Mandela as a “symbol of everything that is good in humanity,” and a man willing to wear the green and gold Springbok regalia that had been created by his former oppressors.

Triumph for the Rainbow Nation

The ex-captain remembers walking out of the changing room and onto the field, “with the sounds of ‘Madiba! Nelson, Nelson, Nelson!’” reverberating around the stadium.

The cheers for Mandela, from a crowd of 65,000 that was almost exclusively white – many who had previously supported his imprisonment – made international headline news. This moment, when South African whites cheered for the ANC leader as much as they did for their beloved rugby team, would come to be a powerful symbol of a changing South Africa.

And when they finally took the field, fired up by Mandela, the Springboks continued this transformation. In a marathon game often described as one of the greatest ever sporting contests, South Africa narrowly beat New Zealand by 15 points to 12, with virtually the last kick of the game.

Critics had called the Springboks “no-hopers,” dismissing any chance the team would do well. But the no-hopers from the multiracial nation that Archbishop Desmond Tutu had described as “God’s rainbow people” had triumphed. A proud and smiling Mandela, still clad in his Springbok rugby jersey, strode onto the field to shake Pienaar’s hand and to present the golden World Cup to him.

“When Madiba handed the trophy to me, I shook his hand, and he said to me, ‘Thank you for what you’ve done for South Africa….’” Pienaar says he was “dumbstruck” when Mandela, who had almost sacrificed his life so that South Africans could be free of racist domination, thanked him – a “mere white rugby player” – for his contribution to the country.

‘Leader’ and ‘Brave One’

Following the historic victory, Mandela maintained contact with Pienaar – even phoning him to congratulate him on the birth of his first son, Jean. “Madiba gave him the Xhosa nickname, Nkokele, which means ‘leader.’ He also told me that Jean would be his godchild,” he says.

A few years later, Mandela invited Pienaar and his family to tea at the former president’s Johannesburg home. The rugby player’s second son, Stefan, was five years old at the time. After the boy begged Mandela to also be his godfather, the Nobel Peace Prize winner hugged him, laughed and declared, “I will call you ‘brave one.’”

Pienaar says, “That just goes to show what kind of a person Madiba is, that he always finds time for all people in life, no matter how small they are. I think absolute humility is his greatest virtue.”

In 2007, in France, the Springboks – this time with new captain John Smit at the helm – again reached the World Cup final. In a videotaped message to the team before the game, Mandela urged them to “play the game hard and honestly, and whatever the outcome – hold your heads high. We are convinced that you will triumph and bring the trophy home.”

The Springboks indeed emerged victorious, beating England to once again win rugby’s most coveted prize.

Pienaar will always be grateful to Mandela for supporting what was then the “white sport” of rugby. But he emphasizes that the freedom fighter should ultimately be remembered more for saving South Africa from what would have been a disastrous civil war.

He says, “Things didn’t go totally wrong in South Africa because we had the most amazing leader, at the right time.”

By supporting rugby, Mandela had suddenly and boldly gained the affection of millions of white South Africans. Analysts agree the strategy probably avoided further tragedy in South Africa. They continue to use it as proof of Mandela’s genius.