In the Johannesburg city center, Lucy Khumalo, a businesswoman, hurries out of a minibus taxi, slams the door behind her and rushes along the overcrowded sidewalks to her office. As she walks briskly, she says, “I understand the Zimbabweans’ situation, but enough is enough.”

Khumalo stops suddenly, dabs at sweat on her face with a paper towel and brushes her pink dress with the back of her hand. She continues, “I mean really, we can’t have the whole world coming to our country when our economy is not good.” And she sweeps into the lobby of the building where she works.

On the streets of South Africa, it’s not difficult to find people willing to voice criticism of the presence of Zimbabwean migrants in South Africa. Usually, the comments take the form of vehement outbursts such as “they are stealing our jobs” and “they are milking our country dry” and “they are committing crime” and “they are marrying our women so that they can stay here forever.”

On a city center pavement, Innocent Ntola rummages in a big white cooler box filled with ice and cans of soft drinks. As he tries to sell these to passersby, he exclaims, “Wherever these Zimbabweans go, they are making babies, filling our country up with Zimbabwean babies! Who must feed all these people? Zimbabwe is for Zimbabweans, South Africa is for South Africans! I will be very happy when they all go home!”

The Zimbabwean dilemma

Elinor Sisulu, a Zimbabwean academic who lives in South Africa, says she understands South Africans’ “bad feelings” about her compatriots. She explains, “It’s easy for the middle classes and international community to be morally outraged and to condemn this xenophobia. But they aren’t the ones living in filthy squatter camps with no water and electricity. They aren’t the ones who are sitting at home all day without work. It’s South Africa’s poor who are hosting all these immigrants, and it’s putting them under even more pressure and leading to tremendous ill feeling.”

A new policy from the South African government says only Zimbabweans who are working, studying or owning businesses in the country can remain here. They must apply for the new residence permits by December 31 or face deportation. Analysts of the new law say it may lead to the expulsions of many thousands of Zimbabweans next year.

The new rules pertaining to migrants have trained the spotlight firmly on what’s become known as “The Zimbabwean Dilemma” in South Africa. For the past decade, as Zimbabwe has experienced wave after wave of political violence and economic failure, its citizens have been flocking across the border to Africa’s most powerful economy in search of safety and better lives for themselves and to earn money for relatives in their homeland.

Much of the migration has been illegal, with the International Organization for Migration estimating there are currently up to two million Zimbabweans in South Africa without legal residence documents. Some NGOs say the actual number is far higher.

South African farmers benefit from Zimbabwean chaos

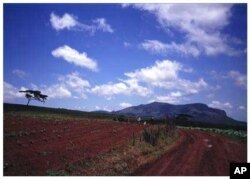

While many South Africans have welcomed their government’s stricter stance on foreign migrants, one very important sector of the country’s economy is extremely concerned about it. South Africa’s agricultural industry employs thousands of Zimbabweans. Many of them are illegal immigrants, working on isolated farms all over the country, out of sight of the authorities.

The Zimbabwean laborers have flooded South Africa because agriculture in their homeland has imploded. White, commercial farmers who were once Zimbabwe’s biggest employers have been murdered; others brutally attacked and driven from their country, their land confiscated by “war veterans” and government officials under President Robert Mugabe’s controversial “land reform” program.

David Cooper – not his real name – says he and many of his fellow South African farmers have “ironically” benefited from the chaos north of the border.

“Well, because of the collapse of organized agriculture in Zimbabwe, we’ve had this massive overflow from Zimbabwe into South Africa of highly skilled farm workers and managers, with many of them having vast experience on big tobacco farms, big maize farms and so on. So all the Zimbabwean agricultural skills have been transferred to South Africa,” he explains.

Cooper is one of South Africa’s top farmers. He’s a leading member of an agricultural association with thousands of members and as such is in regular contact with many of his country’s farmers. He supplies produce to South Africa’s supermarket chains.

“To run an operation like this requires quite a lot of labor. All the weeding is done by hand, all the planting, all the reaping, the packing; the whole lot, all done by hand. I’ve had great difficulty in getting South African people willing to work on a farm,” he says.

This, says Cooper, despite the fact that millions of South Africans are unemployed, and he pays salaries that are far above the state-prescribed minimum wage for farm laborers of about 1,300 rand (US$ 190) per month.

“Every now and again a South African comes here and dips his toes in the water, but after about two or three days of hard work I never see him again,” Cooper comments. When the farmer did employ South Africans – up until about four years ago – he says his farm was “plundered” several times and his life threatened. He holds his former South African workers responsible for these crimes.

“They just never seemed to work. They always seem to be involved in something else, like politics. I caught a few of them breaking into my house.” He says because of these problems he felt “forced” to begin employing Zimbabweans. “(This) was against my nature – because when (Nelson) Mandela was released (in 1990), he said to all of us (farmers), ‘Please create as many jobs (for South Africans) as you can.’ But I feel that I’m a bit of a charlatan, because now I’m creating jobs for Robert Mugabe’s people.”

Breaking the law

Cooper now employs 30 Zimbabwean men and women. He says they’re a “pleasure” to work with. “They are wonderful laborers. They’re very well educated. They have excellent manners. I don’t feel – ever – any threat from them. They have a good sense of humor and fun, and they enjoy their lives.”

But the Zimbabweans Cooper’s employing are working illegally on his farm. They don’t have work permits. They, and the farmer, are breaking the law. But Cooper’s unapologetic.

He explains, “Some of my employees are women with young children. When they come knocking on my door, crying and hungry and begging for work so they can live until the next day, I don’t ask them for papers to prove that they’re here legally. I’m not a bureaucrat or a policeman; I’m a farmer with a human heart. I’m also a farmer who needs good workers.”

But some NGOs and government officials accuse farmers like Cooper of abusing the illegal Zimbabwean workers. They say farmers pay the Zimbabweans “slave wages” and that the migrants have few rights – they can’t belong to labor unions; they can’t complain to any authority about ill-treatment at the hands of farmers, as they’d be revealing their illegal status if they did so.

“Look, there are undoubtedly some South African farmers who are exploiting the Zimbabweans. I myself could easily exploit them!” Cooper exclaims. “I could get Zimbabweans to work for me for 400 rand (US$ 60) a month if I wanted to. But they wouldn’t work properly. And what a stupid thing that would be.”

Then he points to one of his Zimbabwean laborers working nearby, and says, “I am not going to ask this lady to identify herself but she can confirm to you that when people start (working) here, they start at the minimum wage. They get paid fairly. If I think they’re worth more, then I’ll pay them more. And I do.”

Cooper emphasizes all the farmers he knows are “just grateful to have the Zimbabweans here, and they pay them a decent wage.”

Tortured with barbed wire

Cooper’s manager is a Zimbabwean. He has a degree from one of the world’s best universities. The farmer sighs, “He should be my boss. He’s one of the most intelligent people I’ve ever met. He should have a top job in Zimbabwean agriculture.”

But, in 2000, while employed on a farm in Zimbabwe, Cooper’s manager joined the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC). One day, a group of “war veterans” aligned with Mr. Mugabe’s ZANU-PF party “kidnapped” him.

“He was tied down and beaten across his back with barbed wire, so that he spent three months in hospital. His whole back is just one mass of scar tissue,” Cooper says. “He still has a lot of problems because of that severe torture.”

Despite the obvious human rights violations Cooper’s manager has suffered, and despite his numerous applications for asylum, the South African authorities have yet to grant him refugee status. Because of his exceptional qualifications, Cooper’s manager has also applied a number of times for a “special skills” residence permit but has been rejected every time.

An exasperated Cooper asks, “Is it any wonder then that so many Zimbabweans choose to remain underground and not to enter this new documentation process? They’re just totally cynical about any regulations formulated by both the South African and the Zimbabwean governments.”

Take their chances

The farmer says his Zimbabwean workers have chosen not to try to obtain the new temporary residence permits. One of the requirements to apply for the documents is that applicants must possess valid Zimbabwean passports.

“Some of my people don’t have passports,” says Cooper. “They ran away from Zimbabwe because they were considered enemies of Mugabe. Now it’s expected of them to march into a Zimbabwe government office and apply for a passport from their enemies? Ridiculous.”

The South African government has made it clear that applying for the new permits, even if one conforms to all the necessary requirements, is no guarantee of success. “My people are afraid of being rejected and then prosecuted for working for me illegally,” says Cooper. “At least if they choose to stay here with me, they remain out of sight, they have jobs and an income, and I’ll continue helping them to get their money to their families back in Zimbabwe.”

The farmer says his workers will also continue to “take their chances” with the police. “In the past, local police have detained them, and all the police did was ask for bribe money…. (The worker then) gives them 50 or 100 bucks and they say, ‘Right, off you go,’” the farmer explains.

Warning to authorities

South Africa’s police chief, General Bheki Cele, has made frequent statements to the effect that he’s dedicated to ending corruption in the police force. But Cooper maintains most South African police officers aren’t interested in enforcing the law regarding illegal migrants, but rather in “milking these poor people.”

He says, “In this district we have had break-ins, farmers have been attacked, our implements have been stolen – and the police don’t investigate. I had 33 burglaries in five months at one stage and the police never investigated one. Yet they would invade my farm whenever they wanted to demand bribe money from my workers.”

Cooper says this behavior by the police ended recently when he and other “furious” farmers from the district visited their local police station, vented their anger at the station commander and demanded an end to the police harassment.

“I told them they must start investigating real crimes, not Mickey Mouse ones. I’m not scared of the police; they don’t come on to my property (anymore). They know they’re not welcome,” he emphasizes.

But Cooper is, after all, breaking the law by employing migrants without work permits. The farmer, though, remains defiant, commenting, “I am the king on this farm; nobody else. And if I choose to employ people illegally, that’s my business….”

Cooper warns the authorities of “negative fallout” if they deport thousands of Zimbabwean farm workers. “This government must think before it expels Zimbabweans en masse. This country cannot afford to lose them. If it does, food production here will decline dramatically,” he predicts.

Cooper says of the many farmers he advises and is in contact with, many “rely almost completely” on Zimbabwean labor. He warns, “If we removed the Zimbabweans from South Africa now, the gross national agricultural product I would say would probably drop in half, immediately.”

In reaction, South Africa’s chief of immigration, deputy director general of Home Affairs Jackie McKay, says, “Obviously Zimbabwean farm workers are benefiting some South African farmers, but I can’t comment about what effect their absence would have on agriculture or the economy. All I can say is that we urge all Zimbabwean farm workers in South Africa to enter the documentation process so that they can work legally.”