Members of the patient advocacy group the Treatment Action Campaign are spending a lot of time at funerals in the Free State these days.

“People are dying because the provincial health department is failing to give them the ARVs,” says Thabo Nkwe, a fieldworker for the organization, which lobbies government to give the medicine to all HIV-infected people who need it.

The TAC has collected statements from HIV-infected people in the Free State who blame the provincial health department for their worsening conditions. “People haven’t been given drugs, so they’re getting sicker and sicker. They’re dying,” says Nkwe.

Until recently, nurses said they were rationing the pills, afraid that they’ll run out before new funding arrives.

A provincial health official responds

The South African government has promised to provide ARVs at certain state hospitals and clinics to HIV-infected people with immune systems that are dangerously weak, and vulnerable to opportunistic infections.

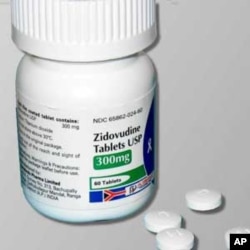

Doctors measure the strength of the immune system by counting the quantity of CD4 cells in the body. Someone with a CD4 count of below 200 has a severely compromised immune system and is in danger of getting an infection and dying. Doctors usually prescribe anti-retrovirals to try to improve the CD4 count.

Yet, in various parts of the Free State, people with CD4 counts of below 50 are being refused antiretroviral treatment at state medical institutions.

In an interview with VOA, the Free State health minister, Sisi Mabe, said there are “no problems at all” with the province’s response to HIV/AIDS.

With regard to access to anti-retrovirals, Mabe told VOA it is “dangerous” to prescribe them immediately. She said people with such weak immune systems needed to undergo “rehabilitation” through “nutritional therapy” before being given ARVs, failing which they’d develop “negative reactions” to the drugs.

She also said it took “only a matter of weeks” for patients to receive ARVs, but eventually acknowledged that it could take up to three months.

The Johanna Mohajane tragedy

Activists complain that some never get them.

Johanna Mohajane, a 40-year-old HIV-infected woman died recently at the National District Hospital in Bloemfontein, the capital of the Free State. Medical records show Mohajane had tuberculosis and meningitis – two common consequences of untreated HIV infection. The documents show also that state medical staff did not give Mohajane ARVs. Her family blames Mabe’s department for her death.

Mabe said she’d investigate this case, as well as other similar cases VOA brought to her attention. But, more than a month later, the people involved say neither the minister nor any of her staff has contacted them.

A source at the National District Hospital did, however, inform VOA that Mabe’s office had contacted the facility’s chief, demanding an explanation of the death of Johanna Mohajane. “We are investigating the case as we speak,” the source said.

Charges of mismanagement

In July 2009, the Free State health minister disclosed that her department had 230 million rands (US$ 31 million) available to it, and that most of this money would be spent on purchasing ARVs for the province. The minister says the money was spent on exactly this, “which is why we have enough stock now.” But the TAC charges the ministry has misspent money.

The TAC’s Sello Mokhalipi says he attended one of several gala dinners and special events sponsored by the ministry, and he characterized these richly-catered affairs as a waste of resources which should be spent on the sick. Mabe responded by saying, “Since I was an MEC (minister) in this department, I have never seen any party organized by the department. We don’t have such things. We have even cut costs on catering, when we have meetings.”

Opposition parties have also criticized Mabe for accepting a luxury Mercedes Benz vehicle bought by the government with taxpayers’ money, while there’s not enough money for ARVs in the Free State.

In a reaction that has angered health activists and HIV-positive people who can’t access ARVs in South Africa, Mabe described her government’s purchase of a fleet of cars worth almost 20 million rands as a “saving.”

She told VOA, “It’s a saving because it was buying in bulk. And in everything if you buy in bulk, there’s always a discount and there’s always less money that you spend than buying things (singly). That’s our take on the matter.”

Mabe says people in the Free State, including the poor and those who urgently need ARVs, are “fine” with her driving a limousine.

The national government responds

Several HIV experts, and even South Africa’s national health minister, Dr. Aaron Motsoaledi, have reacted publicly to Mabe’s comments.

They said her views on the need for nutritional therapy before starting on anti-retrovirals is not scientifically correct. They said HIV-infected people with low CD4 counts needed to begin taking ARVs as soon as possible, if their lives were to be saved.

Motsoaledi said he had spoken with Mabe about her comments to VOA about “the need to avert “negative reactions” to ARVs by first giving patients “nutritional therapy.” “She denies she ever said that; she says she was misunderstood,” the national minister said – despite the VOA recording of her comments.

Nevertheless, Motsoaledi said he’d informed Mabe that “the question of whether somebody is reacting (negatively) to ARVs must be left to doctors; it can’t be an issue determined by politicians.”

Motsoaledi acknowledged drug shortages and rationing, which Mabe denied.

“I don’t know why she (Mabe) said this,” Motsoaledi said. “There is definitely acceptance on our part that there are problems regarding distribution of ARVs…in the whole country, not only in the Free State.”

Motsoaledi has moved quickly to address the problems. He sent senior officials, including his deputy, to the Free State, and they confirmed much of what VOA found. He has met with the managers of all South African state medical facilities to instruct them that under no circumstances should nurses ration ARVs, and to instill in them the importance of proper management of the country’s ARV stocks.

But, he said he has no control over how provincial health departments, which are under the authority of provincial governments, spend their budgets.

“All I am able to do is recommend strongly that the money gets used to improve health services in the country; my responsibility ends there,” he told VOA.

Motsoaledi says no medical facilities will run out of the medicines in the near future. “We are determined to make these problems part of our past,” he said.

But South African health workers agree that challenges will remain. The government says it will provide ARVs to 900,000 people by March next year, but health experts assert this figure is likely to be closer to 300,000 because – even with the necessary medicine stocks – South Africa doesn’t have enough trained public sector doctors and nurses to dispense this quantity of drugs, and to instruct people to take the pills properly.

MAKE YOUR OPINION HEARD IN AFRICA

We'd like to hear what you have to say. Let us know what you think of this report and other news and features on our website. E-mail your views about what is happening in Africa to: africa@voanews.com or fill out the form below.

You may also telephone us and leave a message. In the US, call: (202) 205-9942. After you hear the VOA greeting, press the number "30" and leave your message for potential use it our daily broadcasts.