Throughout the scraggliest parts of the American West, in fields where jackrabbits keep company with rattlesnakes, you see symbols of an earlier era of prosperity.

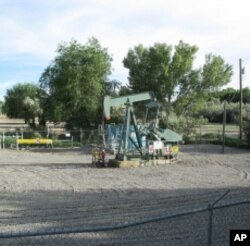

Often rusted, but sometimes new and shiny, they look like tireless grasshoppers, bobbing up and down, up and down, up and down across the landscape. Sometimes you'll see a lone one in an unlikely place, such as the parking lot of a shopping mall, the middle of a wheatfield, or out by the clothesline in someone's backyard.

They go tha-thump, tha-thump, tha-thump, day and night.

These are motor-driven oil pumps, whose proper name is hydraulic pumping unit. Most people call them pumpjacks, horseheads or - our favorite - nodding donkeys because they look like a pack animal, lazily reaching down for a snatch of grass and then raising its head again.

Pumpjacks are not an explorer's device. They show up long after someone else has prodded the earth and struck oil, long after pent-up natural gas has pushed the oil to the surface in a great geyser, and long after someone capped the gusher and began to harvest the oil. In states like Oklahoma and Texas, where decaying, 100-million-year-old plant and animal debris had turned to oil under the compressed rock, fortunes were made and huge companies founded off this liquid black gold.

But when the natural gas is gone, and big platform rigs have finished sucking out the easy-to-reach oil, landowners set out pumpjacks to tap the oil that still oozes through the rocks below - like the moisture you can find in a sponge that's been squeezed.

With one or a few of these horseheads a-pumping, pulling oil into retaining tanks to await shipment to market, families can collect enough barrels of oil to make some extra money.

Pumpjacks can rise and dip day after day without ceasing. But most U.S. states force their owners to stagger the hours of pumping, for fear the vast fields below will be depleted. So don't be fooled if you see an old nodding donkey standing idle, rusting in the sun. It could just be waiting its turn.