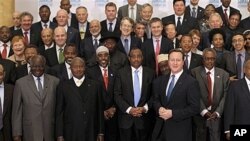

A conference in London on the future of Somalia has brought together an impressive range of leaders from around the world and from Somalia's own abundant roster of political administrations. But average Somalis say some important voices have been left out of the conversation.

The British Foreign Office has set out an ambitious agenda for the London Conference: getting 40 countries to agree on a way forward for a country that has been without a central government for 20 years.

There have been many past efforts, including the Ugandan-mediated Kampala Accord and the U.N.-backed Djibouti peace process as well as negotiations in Nairobi that established the Transitional Federal Government (TFG).

Abdi Samad, an independent political analyst in Nairobi, is optimistic that the London conference will be more successful, because it brings together more divergent parties.

“What I'm saying is, they invited [TFG President] Sheikh Sharif, they invited Puntland, they invited Somaliland, they were not part of the Somali peace process [but] today they bring [them] on board," he says. "With the combination of so many factors, I hope I can see a light at the end of the tunnel."

Representatives of the breakaway Somali region of Somaliland, and the semi-autonomous Puntland and Galmudug regions, are all attending the conference.

While still technically a part of Somalia, all three regions have established their own governments and made strong gestures toward independence, rankling members of the TFG that want to maintain a united Somalia.

But another, more powerful force tearing the country part - the militant Islamist group al-Shabab and its allies - remains unrepresented.

Mohammed Ali Mohamud, a businessman with interests in Puntland and once a prominent vice minister in a previous transitional government, says it is a mistake to leave the Islamists out.

"The people, they are dealing with are one side of the problem," says Mohamud. "So if you don't deal with the whole problem - with all the factions fighting there - then you are only siding with one section and nobody knows what the [other] section will produce."

It would be impossible to get many of the stakeholders in London to sit down with al-Shabab; the United States considers the al-Qaida-linked group a terrorist organization, while Kenya is in the midst of a military operation to crush the militants in southern Somalia. U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has said the U.S. supports all Somalis who denounce violence, but that Washington is "adamantly opposed" to negotiating with al-Shabab.

But Mohamud says Somalia's Muslim partners should be more willing.

"Those who are thinking they are fighting because of Islamic value, you know, Turkey and Qatar or whoever, they can counter-balance," he says. "They say you are Muslim, we are Muslim, let's talk and stop fighting."

A communique from the conference, leaked earlier on Somali websites, recognizes the emergence of new "actors" in Somalia, specifically Turkey and Qatar.

Without a central government, Somalis are often caught up in constant competition between local administrations, militias and even foreign armies vying for control.

For example, the tiny, dusty town of Tabda: Not far from the Kenyan border, Tabda is part of the semi-autonomous region of Azania. Previously under the control of al-Shabab before TFG forces and Kenyan troops repelled the militants, the town is now guarded by a TFG-allied militia.

Here in Tabda, Ibrahim Mahamoud Mohamed, a village elder at the age of 38, says all the people really want is peace.

"Even those militias in the bushes can also be brought into the negotiations," he says. "It is important to know that nothing can be solved through fighting."

But for Mohamed and many others in Tabda and similar towns, food remains scarce, health care is provided by aid workers, violence is a constant threat and London is very, very far away.

Some Somalis Say Critical Voices Absent in London

- By Gabe Joselow