Smartphones are opening up a new way to save lives in some U.S. and European cities, where emergency dispatch centers send mobile phone alerts to nearby citizen responders when a person needs cardiopulmonary resuscitation - or CPR - in a public place.

Last September, Karen Garrison learned just how much of a lifesaver the service can be. She was shopping with her children in Spokane, Washington, when her youngest child, baby Nolan, stopped breathing.

"It was such a blur,” she remembers. "Someone yelled, 'Call 911! He's not breathing.' He was blue."

Garrison, who doesn’t know CPR, held her child while the shopkeeper dialed for help.

About a block-and-a-half away, master mechanic Jeff Olson was fixing a car at the Perfection Tire garage when his smartphone squawked to life.

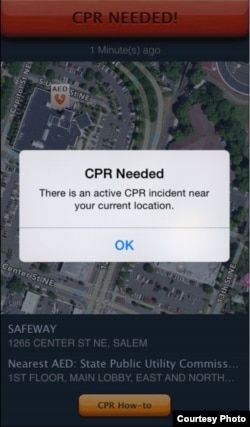

"The phone went off,” he said. “I thought, ‘that's kind of strange.' I looked down and it said, 'CPR needed.' It gave me an address. And I'm going, ‘Wow, that's just a short [distance away]’."

Olson also volunteers with rural ambulance crew, so he knew seconds counted. After washing his hands, he dashed to the scene and took control of the situation.

“I asked her [the mother] what's happening and then scooped up the baby and put him in my arm and started doing some rescue breathing for him," Olson said.

Life-saving smartphone app

Six months earlier, Olson had downloaded a free smartphone app called PulsePoint. The app automatically notifies users when there's a cardiac emergency nearby. It's tied to participating emergency dispatch centers in the U.S. and Canada - and soon Australia, too.

PulsePoint was invented about five years ago by a fire chief in northern California. Many emergency medical teams are based in fire stations.

Spokane Fire Department Assistant Chief Brian Schaeffer explains the idea behind the app is to get trained bystanders to start CPR while medics are still on the way.

"The more responders we can get there that can switch out [do] CPR and keep that person's blood pumping until we have professional responders there, the more likely that person is going to survive," he said.

Earlier this month, the New England Journal of Medicine published the results of a randomized, controlled trial in Stockholm involving volunteers trained in CPR and a mobile phone technology similar to PulsePoint.

That study determined the targeted mobile phone alerts significantly increased the likelihood that cardiac arrest patients received CPR from a bystander.

Schaeffer says that since his department introduced PulsePoint early last year, the app has triggered an alert to citizen responders within 400 meters of an incident about 150 times. A percentage of those made a life-saving difference, although the chief can't say exactly how many.

Good Samaritans emerge in varying ways, he notes, and then often disappear before they can be debriefed and thanked.

"Anybody can be a rescuer. It is that simple. In fact traditionally, we used to teach CPR in fire stations," Schaeffer said. "We don't do that anymore. It's all on the Internet."

In the case of baby Nolan, the nearest fire engine was on another call. So it took more than five minutes for medics to arrive. Citizen responder Jeff Olson and the PulsePoint app got credit for saving the infant's life.

Schaeffer has received questions from community members, concerned that PulsePoint will compromise privacy. He explains that the app shares users' current location with 911 call centers, but cannot track a person over time, or transmit the app user's name. Nor do citizen responders receive the name of a person in distress, only the address at which CPR is urgently needed. The bystander alert software is programmed to exclude cardiac arrest calls from private homes, so those do not trigger a PulsePoint activation.

And Schaeffer stressed, "There is no risk to a Good Samaritan that renders aid," so there is no liability for life-saving actions that are ultimately not successful.

Spreading the word

Jeff Olson did not know the Garrison family before that fateful September day, but now, eight months later, they've become reacquainted under happier circumstances. Baby Nolan has underlying health issues, but has made a full recovery from the respiratory arrest episode. His father, Mike Garrison, now wants everyone at the coffeehouse he owns trained in CPR and signed up with PulsePoint.

"This is the point of the app on your phone," he said. "It's not just Angry Birds [a video game]. It is not just things to waste your life. It's actually... a perfect example of a selfless app that is there to help other people."

PulsePoint's acceptance by U.S. emergency dispatch centers has been uneven. Some departments discovered their dispatch software is incompatible. Others place higher priority on other upgrades.

Similar systems to enlist citizen volunteers to respond to nearby cardiac emergencies have emerged independently in the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden. A new addition to the technology is to broadcast the location of the nearest defibrillator, so a volunteer can potentially get it and bring it to the scene. Those machines deliver a shock to restart heartbeats.