In his State of the Union address, President Barack Obama devoted most of a limited section on foreign policy to the Middle East but uttered not one word about that region’s most populous and influential nation: Egypt.

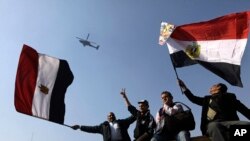

Three years after Obama pressured President Hosni Mubarak to step down in the face of widespread protests and praised the stirrings of democracy in Tahrir Square, the U.S. appears at a loss about what it can do to temper a resurgent military dictatorship in this long-time ally.

Just a day before Obama spoke, Egypt’s top generals blessed the incipient presidential candidacy of Defense Minister Abdel Fatah al-Sissi, who elevated himself from mere general to field marshal. Meanwhile, former President Mohamed Morsi, freely elected in 2012 and toppled in a “coupvolution” last summer, appeared in a sound-proof cage in court during of one of the myriad judicial proceedings against him.

The Obama administration has suspended delivery of F-16s and Apache helicopters to Egypt, but continued other military aid to help the Cairo government fend off al-Qaida-linked militants in the Sinai. The U.S. has also criticized Egypt for outlawing the Muslim Brotherhood and arresting scores of secular opponents including many of the young activists responsible for the initial 2011 revolution.

Assistant Secretary of State Anne Patterson, a former U.S. ambassador to Egypt now looking after U.S. policy toward the entire Middle East, said in her first interview since assuming the post, “It’s certainly no secret that we’re concerned about freedom of the press, freedom of association, all the fundamentals that are being thrown into question right now in Egypt, not to mention the huge economic issues.”

Patterson also expressed concern about upcoming presidential and parliamentary elections, which are likely to offer limited choices. She said that future U.S. aid – some of which requires the Obama administration to certify that Egypt is on a democratic path -- could depend “on the nature of the elections and the environment in which they are held.”

However, bolstered by billions more in assistance from Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states that supported Mubarak and opposed Morsi, Egypt’s current rulers seem impervious to U.S. pressure. In the Egyptian press, America is a scapegoat for Egypt’s dysfunction, not the benefactor and key ally of more than three decades.

Patterson, while she was U.S. ambassador to Egypt from 2011 until last year, was often accused in the Egyptian media of being soft on the Muslim Brotherhood – a charge that the government-controlled press continues to make about the Obama administration. A journalist and former parliamentarian, Mustafa Bakri, went so far last week as to exhort Egyptians to kill Americans. Bakri later retracted the remark but the implications were ominous.

“There has been a rash of hugely anti-American stuff in the press,” Patterson said in the interview with this author for the Al-Monitor website. This ebbs and flows… [But] it’s a really quite dangerous game because you fan up public opinion and then you’re hostage to public opinion.”

It is hard to gauge just how popular al-Sissi really is. Much of the support for him appears to emanate from Egyptian weariness with their roller coaster politics, the weakness of liberal forces, the deteriorating economy and growing insecurity. Car bombs are going off now with frightening regularity in Cairo, the jails are full of Muslim Brothers and secular critics of the government, and tourism and investment remain depressed.

Shibley Telhami, author of a new book on Arab public opinion, “The World through Arab Eyes,” says al-Sissi’s popularity is likely to be ephemeral.

“If al-Sissi gets elected, he’ll have a honeymoon and in six months, he’ll be judged,” Telhami said. “Did he improve the economy, increase jobs?”

According to Telhami, the region has changed too much for al-Sissi to be transformed into Egypt’s next president for life. The explosion of satellite television and social media means that even Egypt’s current crackdown on dissent cannot muffle all opposition voices indefinitely.

“We’ve seen public empowerment on a scale we’ve never witnessed before,” Telhamy says of the Arab awakening that began in Tunisia in late 2010. “It’s not going to go backward, it’s going to go forward. You can’t put the genie back in the bottle.”

With limited means to influence Egypt’s next political steps, Patterson said one focus of her tenure would be to try to deal with the root causes of instability in the region through promoting free trade and economic development zones.

“We’re going to … focus more on economic issues because the genesis of many of these problems is economic,” she said. “It’s essentially demographics plus unemployment plus extremely poor education.”

Patterson noted that U.S.-backed Qualifying Industrial Zones in Egypt had created 300,000 jobs and generated $1 billion in exports and said she hoped the program could be expanded.

She also said that breakthroughs on historically intractable issues such as the Iranian nuclear program and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict could yield big benefits and make lesser conflicts easier to resolve.

If you can move “these big issues off the plate … you have a much better situation throughout the region,” she said.

Three years after Obama pressured President Hosni Mubarak to step down in the face of widespread protests and praised the stirrings of democracy in Tahrir Square, the U.S. appears at a loss about what it can do to temper a resurgent military dictatorship in this long-time ally.

Just a day before Obama spoke, Egypt’s top generals blessed the incipient presidential candidacy of Defense Minister Abdel Fatah al-Sissi, who elevated himself from mere general to field marshal. Meanwhile, former President Mohamed Morsi, freely elected in 2012 and toppled in a “coupvolution” last summer, appeared in a sound-proof cage in court during of one of the myriad judicial proceedings against him.

The Obama administration has suspended delivery of F-16s and Apache helicopters to Egypt, but continued other military aid to help the Cairo government fend off al-Qaida-linked militants in the Sinai. The U.S. has also criticized Egypt for outlawing the Muslim Brotherhood and arresting scores of secular opponents including many of the young activists responsible for the initial 2011 revolution.

Assistant Secretary of State Anne Patterson, a former U.S. ambassador to Egypt now looking after U.S. policy toward the entire Middle East, said in her first interview since assuming the post, “It’s certainly no secret that we’re concerned about freedom of the press, freedom of association, all the fundamentals that are being thrown into question right now in Egypt, not to mention the huge economic issues.”

Patterson also expressed concern about upcoming presidential and parliamentary elections, which are likely to offer limited choices. She said that future U.S. aid – some of which requires the Obama administration to certify that Egypt is on a democratic path -- could depend “on the nature of the elections and the environment in which they are held.”

However, bolstered by billions more in assistance from Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states that supported Mubarak and opposed Morsi, Egypt’s current rulers seem impervious to U.S. pressure. In the Egyptian press, America is a scapegoat for Egypt’s dysfunction, not the benefactor and key ally of more than three decades.

Patterson, while she was U.S. ambassador to Egypt from 2011 until last year, was often accused in the Egyptian media of being soft on the Muslim Brotherhood – a charge that the government-controlled press continues to make about the Obama administration. A journalist and former parliamentarian, Mustafa Bakri, went so far last week as to exhort Egyptians to kill Americans. Bakri later retracted the remark but the implications were ominous.

“There has been a rash of hugely anti-American stuff in the press,” Patterson said in the interview with this author for the Al-Monitor website. This ebbs and flows… [But] it’s a really quite dangerous game because you fan up public opinion and then you’re hostage to public opinion.”

It is hard to gauge just how popular al-Sissi really is. Much of the support for him appears to emanate from Egyptian weariness with their roller coaster politics, the weakness of liberal forces, the deteriorating economy and growing insecurity. Car bombs are going off now with frightening regularity in Cairo, the jails are full of Muslim Brothers and secular critics of the government, and tourism and investment remain depressed.

Shibley Telhami, author of a new book on Arab public opinion, “The World through Arab Eyes,” says al-Sissi’s popularity is likely to be ephemeral.

“If al-Sissi gets elected, he’ll have a honeymoon and in six months, he’ll be judged,” Telhami said. “Did he improve the economy, increase jobs?”

According to Telhami, the region has changed too much for al-Sissi to be transformed into Egypt’s next president for life. The explosion of satellite television and social media means that even Egypt’s current crackdown on dissent cannot muffle all opposition voices indefinitely.

“We’ve seen public empowerment on a scale we’ve never witnessed before,” Telhamy says of the Arab awakening that began in Tunisia in late 2010. “It’s not going to go backward, it’s going to go forward. You can’t put the genie back in the bottle.”

With limited means to influence Egypt’s next political steps, Patterson said one focus of her tenure would be to try to deal with the root causes of instability in the region through promoting free trade and economic development zones.

“We’re going to … focus more on economic issues because the genesis of many of these problems is economic,” she said. “It’s essentially demographics plus unemployment plus extremely poor education.”

Patterson noted that U.S.-backed Qualifying Industrial Zones in Egypt had created 300,000 jobs and generated $1 billion in exports and said she hoped the program could be expanded.

She also said that breakthroughs on historically intractable issues such as the Iranian nuclear program and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict could yield big benefits and make lesser conflicts easier to resolve.

If you can move “these big issues off the plate … you have a much better situation throughout the region,” she said.