As Egypt holds its first free presidential election, the future of its already fragile 33-year peace treaty with Israel again emerges as a hot topic of international foreign policy concerns. Among the issues central to the treaty is the future of the poverty-stricken and politically unstable Sinai Peninsula - a swath of land that has figured prominently in the two countries’ often-bumpy relations.

Since the fall of president Hosni Mubarak and the precipitous decline of Egypt’s domestic security operations, portions of the Sinai Peninsula have turned from poorly controlled to downright lawless. From among the more than 30 Bedouin tribes of the Sinai, some entrepreneurial armed gangs, working alongside Islamic militants, have transformed border areas of the northern governate into a haven for the smuggling of drugs, refugees from Africa, and weapons for extremists threatening the security of Egypt’s neighbor, Israel.

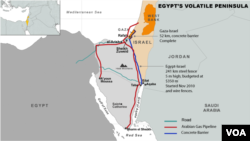

The peninsula’s value has increased as Egypt’s growing natural gas industry sends the resource over Sinai pipelines to a regional market east of the peninsula. But local Bedouins - a historically disenfranchised population - have protested official discrimination and economic marginalization. Bedouins cannot legally own land in the Sinai; the government estimates only 13 percent of northern Bedouins are employed, and most of them see local jobs going to newcomers from the Nile Valley.

In the three decades since Egypt regained control over the Sinai from Israel, local populations and their needs have been largely ignored by the government in Cairo. But the issue of the Sinai did not go unnoticed in Egypt’s current presidential race. Candidates from across the country’s political spectrum campaigned in the Sinai over recent weeks, promising crowds of Bedouins economic development and increased security.

Observers say that if Egypt’s next president - be it the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi or the former air force commander and short-term prime minister, Ahmed Shafiq, who prevailed in the first round of voting - doesn’t act decisively to develop and restore order in the Sinai, Israel could take matters into its own hands. The Jewish state has already drawn a stark line in the sand with construction of a 150-mile-long electrified steel fence with a layer of razor wire on top to keep African refugees, Egyptians and Arab extremists out. Recently, Israel called in additional troops to make sure the fence does its job.

Tensions escalated in August of last year when armed gunmen with explosives crossed into Israeli territory from the Sinai and killed eight Israelis and wounded 30. Israeli defense forces killed five Egyptian border guards as they hunted down the attackers. Responding to the deaths of the five guards, hundreds of Egyptians staged violent protests at the Israeli Embassy in Cairo, tearing down a security wall and ransacking embassy offices. Embassy staff escaped unharmed.

The 'bomb' factor

Ehud Yarri, a veteran Israeli journalist, discussed the Sinai as a new frontier of conflict recently at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy and called the peninsula a “ticking bomb.”

The Washington Institute’s Egypt expert, Eric Trager later phrased it a bit differently.

“Sinai is not a ticking bomb,” he said. “It is a bomb that keeps going off.” Trager said he thought the events that led to the ransacking of the Israeli embassy were leading to open conflict, but that the two governments “dialed back” the rhetoric and established commissions to examine the causes of the attacks.

Since the beginning of this year - as in years past - life in the Sinai has proven dangerous. Since late January gangs identified as armed Bedouins have kidnapped 24 Chinese workers from a cement plant near al-Arish; two American, three Korean and two Brazilian tourists all were taken hostage in attempts to force Egyptian police to release imprisoned Bedouins. All captives were let go unharmed within a day or two. Bedouins have also kidnapped 19 Egyptian border guards and 10 infantrymen from the Multinational Force and Observers’ (MFO) Fiji contingent.

“Bedouins are reported to have burned several police stations near the Gaza and Israeli borders in the northern governate and 14 separate times unidentified terrorists have blown up portions of a natural gas line near al-Arish in the Sinai that supplies Egyptian fuel - a potential replacement for the diminishing Gulf of Suez oil supply - to Israel and several other Middle Eastern countries.

The principal security threat among Bedouins is a group now led by Saleem Abu Lafi and based in the Wadi Amr area and the Halal Mountains, south of Sheikh Zuweid, said Normand St. Pierre. St. Pierre is a retired U.S. army colonel who was involved with MFO operations in the Sinai. He referred to the Bedouin gangs as well-armed smugglers who operate tunnels beneath eastern borders and “rent the tunnels by the hour.”

St. Pierre described the vast majority of the Sinai’s population of Bedouins as businessmen, fishermen and camel herders, and a largely nomadic population whose tribal leaders settle their own affairs. Egypt’s own forces stationed in the central and western portions of the Sinai have tended to leave the Bedouins alone. After series of violent incidents, however, Egyptian police rounded up and jailed hundreds of Bedouins as suspects.

Economic development: farming, tourism or smuggling?

“The Bedouin believe they have been left out of the region’s tourism and minerals-based economic boom, as employers do not hire Bedouin, preferring to bring in Egyptians from the Nile Valley,” writes Dona Stewart, a fellow at the Center for Advanced Defense Studies and adjunct faculty at the National Defense University’s Near East South Asia Center for Strategic Studies.

“Such economic marginalization, according to the Bedouin, is a primary reason they have turned to smuggling. Weapons, drugs, fuel and African migrants are all trafficked through the area, and those who control this trade have access to significant cash and weapons. Indeed, the Egyptian government’s presence in the Sinai and its relations with the Bedouin have always been security-led.”

Yet there are profits to be made in the Sinai. “Egypt’s tourism industry is a major pillar of the national economy, earning revenues of $10.8 billion in 2009,“ said Stewart, but local Bedouin do not see the profit in the enterprise, and tourism revenues have plummeted with recent violence.

When he was president of Egypt, Anwar Sadat proposed to recruit thousands of Nile Valley residents to cross the Suez and pioneer in the under-populated regions of the Sinai. It never happened. The Al Salaam Canal, a 28-year project to bring water to arid regions of the peninsula, was never finished.

In recent years, officials and businessmen in Sinai’s north have proposed many economic development projects designed to turn Bedouins into farmers: major agricultural projects instead of more cement plants, lengthening the canal to irrigate the central desert for growing cantaloupe, tomatoes and olives, and increased investment in processing plants for the region’s olives and Sinai sand that is shipped to Turkey to make glass. Some members of Egypt’s new parliament now talk about a “grand plan” for the region.

Running for president in the Sinai

Egypt watchers in Washington paid close attention to some of Egypt’s presidential hopefuls as they crossed into the Sinai in recent weeks looking for votes. All made vague promises of economic development and increased security.

A campaign in the Sinai by the second top vote-getter in the first round of elections, Mubarak era prime minister Ahmed Shafiq, has not been reported, but there is evidence that he did reasonably well in the Sinai voting.

Egypt’s Independent newspaper reported on a live blog on of election day that the voting in al-Arish, although low in terms of turn-out, favored Shafiq over Amr Moussa, a former Mubarak foreign minister. Both had run on law-and-order platforms presumably attracting Bedouin voters concerned about the need for improved personal security.

When top vote-getter, Muslim Brotherhood candidate Mohamed Morsi, recently spent two days in the Sinai, he offered generalizations on the themes of development and security. But he presented no tangible plan for how his group would try to address either, said the Washington Center’s Trager.

Morsi did tell voters he would establish a large agricultural development project in the Sinai.

“I think the Brotherhood, like any party running for election, doesn’t have a good idea about how to do it, how much it would cost,” said Trager, who spent two months in Cairo talking to the several of the Muslim Brotherhood’s newly elected members of parliament, and to party leaders.

Experts agree that creating jobs for the Bedouins will take years to accomplish, but dealing with the multitude of security threats will likely demand immediate attention.

Trager asked Brotherhood members whether, after decades of anti-Israeli rhetoric, Egypt faced a military confrontation with Israel over Sinai events, or whether would they be able to “dial it back” and talk to their Israeli counterparts to avoid a conflict.

“In our discussion, what they then concluded was that there is a real need to prevent a crisis by having a stability and development plan for the Sinai, but the actual contours of that plan are extremely vague,” said Trager. “But they do understand that the Sinai will create a major headache for them if it is a source of conflict with Israel. They are genuinely interested in doing something about it,” he added.

Trager said whether Morsi wins or loses in the run-off vote, “What we all know is that the Brotherhood has the best election-day operation, they have the numbers and the top-down organization. Even if he loses, the Brotherhood still controls parliament and will be a player for the ongoing power struggle.”

Security in the Sinai after the election

“I’m quite concerned that this is an area that Mubarak ignored for the last 10 years,” said Steven Cook of the Council on Foreign Relations in a recent panel discussion on the Egyptian elections. Cook said no one know what could happen, if there were a repeat of the August, 2011, cross-border incident.

“It is growing increasingly difficult for the Egyptians to impose their will [in the Sinai],” Cook said. “If Israel decided to use any of the battalions recently authorized to patrol the borders during the Egyptian elections, Egypt has very little capacity to gain control over that territory.”

In the discussion no Egyptian presidential candidates were identified as prepared to deal with such a scenario.

But one thing appears clear - whoever prevails in the second round and becomes president, be it Morsi or Shafiq, will have to do something to address Sinai’s pressing economic troubles and its security vacuum.

Since the fall of president Hosni Mubarak and the precipitous decline of Egypt’s domestic security operations, portions of the Sinai Peninsula have turned from poorly controlled to downright lawless. From among the more than 30 Bedouin tribes of the Sinai, some entrepreneurial armed gangs, working alongside Islamic militants, have transformed border areas of the northern governate into a haven for the smuggling of drugs, refugees from Africa, and weapons for extremists threatening the security of Egypt’s neighbor, Israel.

The peninsula’s value has increased as Egypt’s growing natural gas industry sends the resource over Sinai pipelines to a regional market east of the peninsula. But local Bedouins - a historically disenfranchised population - have protested official discrimination and economic marginalization. Bedouins cannot legally own land in the Sinai; the government estimates only 13 percent of northern Bedouins are employed, and most of them see local jobs going to newcomers from the Nile Valley.

In the three decades since Egypt regained control over the Sinai from Israel, local populations and their needs have been largely ignored by the government in Cairo. But the issue of the Sinai did not go unnoticed in Egypt’s current presidential race. Candidates from across the country’s political spectrum campaigned in the Sinai over recent weeks, promising crowds of Bedouins economic development and increased security.

Observers say that if Egypt’s next president - be it the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi or the former air force commander and short-term prime minister, Ahmed Shafiq, who prevailed in the first round of voting - doesn’t act decisively to develop and restore order in the Sinai, Israel could take matters into its own hands. The Jewish state has already drawn a stark line in the sand with construction of a 150-mile-long electrified steel fence with a layer of razor wire on top to keep African refugees, Egyptians and Arab extremists out. Recently, Israel called in additional troops to make sure the fence does its job.

Tensions escalated in August of last year when armed gunmen with explosives crossed into Israeli territory from the Sinai and killed eight Israelis and wounded 30. Israeli defense forces killed five Egyptian border guards as they hunted down the attackers. Responding to the deaths of the five guards, hundreds of Egyptians staged violent protests at the Israeli Embassy in Cairo, tearing down a security wall and ransacking embassy offices. Embassy staff escaped unharmed.

The 'bomb' factor

Ehud Yarri, a veteran Israeli journalist, discussed the Sinai as a new frontier of conflict recently at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy and called the peninsula a “ticking bomb.”

The Washington Institute’s Egypt expert, Eric Trager later phrased it a bit differently.

“Sinai is not a ticking bomb,” he said. “It is a bomb that keeps going off.” Trager said he thought the events that led to the ransacking of the Israeli embassy were leading to open conflict, but that the two governments “dialed back” the rhetoric and established commissions to examine the causes of the attacks.

Since the beginning of this year - as in years past - life in the Sinai has proven dangerous. Since late January gangs identified as armed Bedouins have kidnapped 24 Chinese workers from a cement plant near al-Arish; two American, three Korean and two Brazilian tourists all were taken hostage in attempts to force Egyptian police to release imprisoned Bedouins. All captives were let go unharmed within a day or two. Bedouins have also kidnapped 19 Egyptian border guards and 10 infantrymen from the Multinational Force and Observers’ (MFO) Fiji contingent.

“Bedouins are reported to have burned several police stations near the Gaza and Israeli borders in the northern governate and 14 separate times unidentified terrorists have blown up portions of a natural gas line near al-Arish in the Sinai that supplies Egyptian fuel - a potential replacement for the diminishing Gulf of Suez oil supply - to Israel and several other Middle Eastern countries.

The principal security threat among Bedouins is a group now led by Saleem Abu Lafi and based in the Wadi Amr area and the Halal Mountains, south of Sheikh Zuweid, said Normand St. Pierre. St. Pierre is a retired U.S. army colonel who was involved with MFO operations in the Sinai. He referred to the Bedouin gangs as well-armed smugglers who operate tunnels beneath eastern borders and “rent the tunnels by the hour.”

St. Pierre described the vast majority of the Sinai’s population of Bedouins as businessmen, fishermen and camel herders, and a largely nomadic population whose tribal leaders settle their own affairs. Egypt’s own forces stationed in the central and western portions of the Sinai have tended to leave the Bedouins alone. After series of violent incidents, however, Egyptian police rounded up and jailed hundreds of Bedouins as suspects.

Economic development: farming, tourism or smuggling?

“The Bedouin believe they have been left out of the region’s tourism and minerals-based economic boom, as employers do not hire Bedouin, preferring to bring in Egyptians from the Nile Valley,” writes Dona Stewart, a fellow at the Center for Advanced Defense Studies and adjunct faculty at the National Defense University’s Near East South Asia Center for Strategic Studies.

“Such economic marginalization, according to the Bedouin, is a primary reason they have turned to smuggling. Weapons, drugs, fuel and African migrants are all trafficked through the area, and those who control this trade have access to significant cash and weapons. Indeed, the Egyptian government’s presence in the Sinai and its relations with the Bedouin have always been security-led.”

Yet there are profits to be made in the Sinai. “Egypt’s tourism industry is a major pillar of the national economy, earning revenues of $10.8 billion in 2009,“ said Stewart, but local Bedouin do not see the profit in the enterprise, and tourism revenues have plummeted with recent violence.

When he was president of Egypt, Anwar Sadat proposed to recruit thousands of Nile Valley residents to cross the Suez and pioneer in the under-populated regions of the Sinai. It never happened. The Al Salaam Canal, a 28-year project to bring water to arid regions of the peninsula, was never finished.

In recent years, officials and businessmen in Sinai’s north have proposed many economic development projects designed to turn Bedouins into farmers: major agricultural projects instead of more cement plants, lengthening the canal to irrigate the central desert for growing cantaloupe, tomatoes and olives, and increased investment in processing plants for the region’s olives and Sinai sand that is shipped to Turkey to make glass. Some members of Egypt’s new parliament now talk about a “grand plan” for the region.

Running for president in the Sinai

Egypt watchers in Washington paid close attention to some of Egypt’s presidential hopefuls as they crossed into the Sinai in recent weeks looking for votes. All made vague promises of economic development and increased security.

A campaign in the Sinai by the second top vote-getter in the first round of elections, Mubarak era prime minister Ahmed Shafiq, has not been reported, but there is evidence that he did reasonably well in the Sinai voting.

Egypt’s Independent newspaper reported on a live blog on of election day that the voting in al-Arish, although low in terms of turn-out, favored Shafiq over Amr Moussa, a former Mubarak foreign minister. Both had run on law-and-order platforms presumably attracting Bedouin voters concerned about the need for improved personal security.

When top vote-getter, Muslim Brotherhood candidate Mohamed Morsi, recently spent two days in the Sinai, he offered generalizations on the themes of development and security. But he presented no tangible plan for how his group would try to address either, said the Washington Center’s Trager.

Morsi did tell voters he would establish a large agricultural development project in the Sinai.

“I think the Brotherhood, like any party running for election, doesn’t have a good idea about how to do it, how much it would cost,” said Trager, who spent two months in Cairo talking to the several of the Muslim Brotherhood’s newly elected members of parliament, and to party leaders.

Experts agree that creating jobs for the Bedouins will take years to accomplish, but dealing with the multitude of security threats will likely demand immediate attention.

Trager asked Brotherhood members whether, after decades of anti-Israeli rhetoric, Egypt faced a military confrontation with Israel over Sinai events, or whether would they be able to “dial it back” and talk to their Israeli counterparts to avoid a conflict.

“In our discussion, what they then concluded was that there is a real need to prevent a crisis by having a stability and development plan for the Sinai, but the actual contours of that plan are extremely vague,” said Trager. “But they do understand that the Sinai will create a major headache for them if it is a source of conflict with Israel. They are genuinely interested in doing something about it,” he added.

Trager said whether Morsi wins or loses in the run-off vote, “What we all know is that the Brotherhood has the best election-day operation, they have the numbers and the top-down organization. Even if he loses, the Brotherhood still controls parliament and will be a player for the ongoing power struggle.”

Security in the Sinai after the election

“I’m quite concerned that this is an area that Mubarak ignored for the last 10 years,” said Steven Cook of the Council on Foreign Relations in a recent panel discussion on the Egyptian elections. Cook said no one know what could happen, if there were a repeat of the August, 2011, cross-border incident.

“It is growing increasingly difficult for the Egyptians to impose their will [in the Sinai],” Cook said. “If Israel decided to use any of the battalions recently authorized to patrol the borders during the Egyptian elections, Egypt has very little capacity to gain control over that territory.”

In the discussion no Egyptian presidential candidates were identified as prepared to deal with such a scenario.

But one thing appears clear - whoever prevails in the second round and becomes president, be it Morsi or Shafiq, will have to do something to address Sinai’s pressing economic troubles and its security vacuum.