The recent cyberattack on Colonial Pipeline, the operator of the largest petroleum pipeline in the U.S., shows how internet criminals are increasingly targeting companies and organizations for ransom in what officials and experts term a growing national security threat.

These hackers penetrate victims’ computer systems with a form of malware that encrypts the files, then they demand payments to release the data. In 2013, a ransomware attack typically targeted a person’s desktop or laptop, with users paying $100 to $150 in ransom to regain access to their files, according to Michael Daniel, president and CEO of Cyber Threat Alliance.

“It was a fairly minimal affair,” said Daniel, who served as cybersecurity coordinator on the National Security Council under U.S. President Barack Obama, at the RSA Cybersecurity Conference this week.

In recent years, ransomware has become a big criminal enterprise. Last year, victim organizations in North America and Europe paid an average of more than $312,000 in ransom, up from $115,000 in 2019, according to a recent report by the cybersecurity firm Palo Alto Networks. The highest ransom paid doubled to $10 million last year while the highest ransom demand grew to $30 million, according to Palo Alto Networks.

“Those are some very significant amounts of money,” Daniel said. “And it’s not just individuals being targeted but things like school systems.”

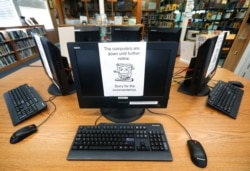

Last year, some of the largest school districts in the U.S., including Clark County Public Schools in Nevada, Fairfax County Public Schools in Virginia and Baltimore County Public Schools in Maryland, suffered ransomware attacks.

The attacks have continued to surge this year, as cybercriminals who once specialized in other types of online fraud have gotten into the lucrative criminal activity. According to a May 12 report by Check Point Research, ransomware attacks increased by 102% this year compared with the beginning of 2020, with health care and utilities the most common target sectors.

Last week, the southern U.S. city of Tulsa, Oklahoma, fell victim to a ransomware attack that rendered the city’s websites inaccessible after officials refused to pay a ransom.

In the span of eight years, ransomware has moved from being an “economic nuisance” to a national security threat, Daniel said.

“This is not putting just an economic burden on society but imposing a real public health and safety threat, and essentially a national security threat,” Daniel said.

Colonial Pipeline Co. CEO Joseph Blount confirmed on Wednesday that he had authorized a ransom payment of $4.4 million on May 7 just hours after a cyberattack took the company’s computer systems offline, disrupting petroleum supplies along the East Coast of the United States.

Colonial’s payment wasn’t the largest ransom paid by a single organization. Last year, Garmin, the maker of the popular fitness tracker, reportedly paid a record $10 million in ransom.

In September, cybersecurity firm CrowdStrike found a ransom demand for a whopping $1.4 billion, according to Executive Vice President Adam Meyers.

While Blount, the Colonial Pipeline CEO, defended his decision to pay a ransom as “the right thing to do for the country,” law enforcement officials and cybersecurity experts say such hefty payments embolden cyber criminals to carrying out more attacks.

“Cybercriminals know they can make money with ransomware and are continuing to get bolder with their demands,” according to a recent report by Palo Alto Networks.

Moreover, researchers at cybersecurity firm Sophos warn that paying a ransom doesn’t pay off. Just 8% of organizations that pay a ransom get back all their encrypted data, according to a new Sophos report based on a global survey of 5,400 IT professionals.

Ransomware victims often pay in cryptocurrencies. A recent analysis found that ransomware victims paid a total of $406 million in cryptocurrencies last year, up 341% from the previous year.

But ransomware is not just about money, say cybersecurity experts and law enforcement officials.

“It is about mayhem,” U.S. Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco said at the Munich Cyber Security Conference last month.

“When the victim is a hospital, we’re talking life and death,” Monaco said. “When the victim is a critical infrastructure, we’re talking the main avenues (for) how we power our grid, how we get our water supply, you name it.”

Last month, the U.S. Justice Department created a task force to develop strategies to combat ransomware.

“This is something we’re acutely focused on,” Monaco said.

In a report to the Biden administration last month, an industry-backed task force called for a more aggressive response to ransomware.

“It will take nothing less than our total collective effort to mitigate the ransomware scourge,” the task force wrote.

In a typical ransomware attack, hackers lock a user's or company's data, offering keys to unlock the files in exchange for a ransom.

But over the past year, hackers have adopted a new extortion tactic. Instead of simply encrypting a user's files for extortion, cyber actors "exfiltrate" data, threatening to leak or destroy it unless a ransom is paid.

Using dedicated leak sites, the hackers then release the data slowly in an effort "to increase pressure on the victim organization to pay the extortion, rather than posting all of the exfiltrated data at once."

In March, cybercriminals used this method when they encrypted a large Florida public school district’s servers and stole more than 1 terabyte of sensitive data, demanding $40 million in return.

“If this data is published you will be subject to huge court and government fines,” the Conti cybercrime gang warned a Broward County Public Schools official.

The district refused to pay.

Cybersecurity experts have a term for this tactic: double extortion. The method gained popularity during the COVID-19 pandemic as cyber criminals used it to extort hospitals and other critical service providers.

“They’re looking to increase the cost to the victim,” Meyers said at the RSA conference.

Recent attacks show cyber criminals are upping their game. In October, hackers struck Finnish psychotherapy service Vastaamo, stealing the data of 400 employees and about 40,000 patients. The hackers not only demanded a ransom from Vastaamo but also smaller payments from individual patients.

This was the first notable case of a disturbing new trend in ransomware attacks, according to researchers at Check Point.

“It seems that even when riding the wave of success, threat groups are in constant quest for more innovative and more fruitful business models,” the researchers wrote.