As countries scramble to control the coronavirus pandemic with stay-at-home orders, millions of people around the world have turned to the internet to work, study and stay informed.

Monday, global internet volume was up more than 40% since the beginning of the year, according to data analyzed by Ookla, a U.S. company that measures online trends.

With workers, students and journalists turning to the internet to conduct meetings, attend lectures and file assignments, the potential for accounts to be hacked and data to be compromised has also shot up.

Even before the pandemic, hackers had been increasingly targeting members of civil society, including journalists, according to a report by Citizen Lab, a research group based in Canada.

In Africa, governments have used popular platforms to target opposition leaders and sway elections. Experts worry attacks will continue to spike as communications move online.

Mark Ostrowski, head of engineering for the U.S. at the Israeli cybersecurity company Check Point Software Technologies, told VOA an increase in online hacks and scams isn’t unexpected.

Ostrowski’s company researches security vulnerabilities and helps organizations fix them.

As services and apps gain popularity, Ostrowski said, so too do the risks for users, presenting significant risks to privacy, finances and free speech.

Hacking press freedom

When journalists become targets, surveillance can interfere with their ability to do their jobs.

“Surveillance is often used as a tool to intimidate journalists or activists not to speak,” David Kaye, the United Nations’ special rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, told VOA’s English-to-Africa's radio program 'International Edition' earlier this year.

“It’s often used as a way to blackmail people to avoid government criticism,” Kaye said, and “it has a very, very serious chilling effect on all sorts of speakers.”

In his role with the U.N., Kaye has been mandated to gather information related to alleged violations of freedom of expression.

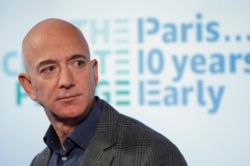

Kaye investigated whether a video file allegedly sent to Amazon founder Jeff Bezos from a phone belonging to Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman installed a program that was used to spy on the billionaire.

Bezos owns The Washington Post, and some experts have said they believe the hacking of his phone was an effort to influence the paper’s coverage of Saudi Arabia.

The surveillance played out over months and involved the surreptitious transfer of data from Bezos’s phone, the Associated Press reported.

Kaye called on the U.S. and other authorities to investigate allegations that the Crown Prince was involved, Reuters reported in January.

Saudi authorities have rejected the allegations. “Recent media reports that suggest the Kingdom is behind a hacking of Mr. Jeff Bezos' phone are absurd. We call for an investigation on these claims so that we can have all the facts out," the Saudi Embassy in Washington said in a January tweet.

Karen Attiah, the global opinions editor at the Post, who recruited Jamal Khashoggi, the journalist murdered in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, said she weighs the risks of messaging platforms when using them in her work.

“I don’t have sensitive conversations, work or otherwise, on WhatsApp,” she told VOA. Attiah said she is cautious when sharing “personal or political information with sources who are at risk from their governments.”

‘Trusting somebody who you shouldn’t be trusting’

Ostrowski’s company works with organizations to alert them of potential loopholes in their software. Tools like WhatsApp, for example, can allow users to share video files. But files can include malignant code that secretly monitors and transmits data.

Most tools offer end-to-end encryption, a kind of technology that ensures communications remain private, making it difficult for third parties, including governments, to eavesdrop on conversations.

But many emerging security problems center around the application itself, not encryption, Ostrowski told VOA.

That means hackers don’t have to break encryption to launch an attack. They merely have to trick the person with whom they’re communicating.

“Because [hackers are] crafting it before it’s sent to the other side, the other side is merely responding to something that’s been crafted, after it’s gone through the encryption,” Ostrowski said.

“You may be trusting somebody who you shouldn’t be trusting,” he added.

Staying safe online takes vigilance, Ostrowski said, especially at moments like the current crisis, when even more aspects of our lives have moved online.

Fortunately, staying alert might go a long way toward keeping us safe.

“A lot of it is common sense,” Ostrowski said. “Who’s going to look after our privacy is you and I.”

This story originated in the Africa Division with reporting contributions from VOA English-to-Africa’s Jackson Mvunganyi in Washington.