Americans' confidence in their police has grown in the past year, but law-enforcement advocates and some social scientists worry that may change because of a recent spate of police killings that could deal a blow to public trust.

Public trust in police rebounded this year after declining to a 22-year low last year following a similar string of highly publicized shootings of blacks by white police officers, some of which led to protests around the country, according to the Gallup research firm.

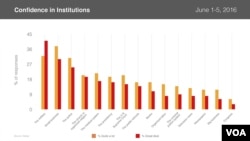

A Gallup survey in June found 56 percent of Americans had "a great deal" or "quite a lot" of confidence in the police, up from 52 percent last year, the lowest number since 1993. By contrast, nine percent expressed confidence in Congress this year and 36 percent in the Presidency.

Frank Newport, a social scientist and editor-in-chief at the Gallup research firm, said that while the changes in public attitudes towards the police are small by historic standards, Americans' trust in major institutions remains troublingly low.

"I’d say, just as a citizen, it's always important that we have confidence in our major institutions because society can crumble if we lose faith in our government, lose faith in our government entities like police, and so forth," Newport said.

In the past week, two African-American men were shot and killed by police officers in Charlotte, North Carolina, and Tulsa, Oklahoma. Protesters have marched in Charlotte every night since Keith Lamont Scott was shot on Tuesday, and Tulsa police officer Betty Shelby was charged with first-degree manslaughter in the shooting death last week of Terence Crutcher.

If claims that Scott was unarmed are proven true, "it is going to further erode the perception of legitimacy of police around the country," said Jonathan Maskaly, an assistant professor of criminology at the University of Texas in Dallas.

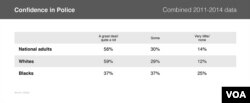

But not all Americans have confidence in their police.

Gallup's combined data for the 2011-2014 period showed that while 59 percent of white Americans had confidence in the police, only 37 percent of African-Americans did.

Newport said trust in the police is already so low in African-American communities that the backlash against the police shooting in Charlotte probably won't have a "dramatic effect" on public attitudes.

Maskaly added that the fact that “only six in ten White Americans have confidence in police isn’t exactly a stellar endorsement of police either.”

Effect of anti-police protests

Even harder to measure is the degree to which Black Lives Matter, the three-year-old movement leading anti-police protests around the country, has influenced attitudes.

Gallup has not gauged Black Lives Matter's impact, but Newport said: "These movements get visibility, and they're publicized, and then some attitudes may fluctuate, but it's very hard for us to say, casually, ‘Aha, that actually caused some change,' that Black Lives Matter had this effect or that effect."

Police advocates blame the group for turning public opinion against law enforcement.

"It's been very, very detrimental" to public confidence in police, said Randy Sutton, national spokesman for Blue Lives Matter, a police advocacy organization established in response to Black Lives Matter. "The same people that are talking about bias and prejudice from police are creating prejudice and bias toward police."

The fact that a large segment of the population, both black and white, doesn't trust the police "worries me tremendously," said Sutton, who served more than three decades with the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department. "Besides worrying me, it frustrates me."

Spillovers

Public confidence measures can be misleading, Maskaly said, adding that a better measurement is public perception of police legitimacy.

With an estimated 17,000 police departments in the United States, the Texas criminology professor said police-community relations vary from precinct to precinct, with some agencies reporting high levels of community trust.

"The other day I was on a panel on community relations in Plano, Texas, and community relations in Plano are invariably higher than 56 percent," Maskaly said. "But if you go to other places, it might be lower than the general population."

What worries Maskaly and other social scientists, as well as police advocates, is that the backlash in Charlotte could spill over and undermine perceptions in communities with no history of police abuse.

"You could see a vicarious experience in other parts of the country simply because the assumption is police in Charlotte [are] doing this, and, therefore, police in other places [are] also doing this," Maskaly said.

The protests in Charlotte may be over the shooting of Scott, but their underlying causes run deeper than Scott's controversial death, Maskaly said.

"Oftentimes, communities — especially members of minority groups — often feel they're not receiving the same treatment as other members of society," Maskaly said. "That's the source of frustration, that society and police treat them differently."

More than 700 people have been killed by police so far this year, but that is a tiny fraction of police interactions with the public. According to the National Institute of Justice, less than 1 percent of interactions result in use of force, and then it is mostly nonlethal.

Community policing

To respond to the crisis over policing in America, policymakers and experts have advocated community policing, under which police are sent into communities to work on problems. But that much-touted practice has not had an impressive track record of making communities safer, said James Nolan, a professor of sociology at West Virginia University.

What is needed instead, Nolan says, is "community building."

Rather than providing incentives for making street-level arrests, as is the current practice in many police departments, police should work with communities to build safer neighborhoods, the sociologist said.

To show how community action can galvanize public attitudes — in this case in a negative direction — Nolan cited the proliferation of "stop snitchin'" campaigns, in which criminals pressure community members not to cooperate with police.

Because a large number of crimes in these neighborhoods don't get prosecuted, "People say, ‘What's the point of even calling the police?' Therefore, it erodes public confidence," Nolan said.

More troubling is that "stop snitchin'" campaigns have "made people not even want to call the police when a crime occurs."