When American poet Emily Dickinson wrote the lines, "I'm Nobody! Who are you? Are you — Nobody — too? Then there's a pair of us!", she might have been writing about the women and men who tended her kitchen hearth and household grounds in the quiet country town of Amherst, Massachusetts.

Except that the 19th century poet, who yearned for privacy, became a famous "Somebody," while her maids and stablemen, gardeners and laundry workers were forgotten. But those "nobodies" — long lost to history — are about to be recognized for their contributions to American literature with the publication of "Maid as Muse: How Servants Changed Emily Dickinson's Life and Language."

Maid as Muse

Emily Dickinson wrote almost 2,000 poems and countless letters. Her literary style is instantly recognizable — short sentences, partial rhymes and unconventional punctuation.

"Her language is incredibly exciting, even now," says writer Aife Murray. "So, you can't really just say she was a 19th century writer. She is really still sending literary shockwaves. Her language is that fresh, that exciting."

Dickinson's poems often got their start in her kitchen, where she spent a large portion of each day, baking. She would draft poems on the back of recipes, shopping lists, chocolate bar wrappers, pharmacy flyers and wings of envelopes.

"Before she had a maid, she was in there cooking and doing all of the baking," Murray says. "When a maid was hired to permanently work in the kitchen, Dickinson actually remained in the kitchen to write."

Extended family

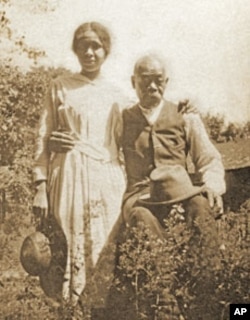

Over the years, Dickinson had hired an ethnically diverse group of servants: African American gardeners, Yankee seamstresses, Native American laborers, stablemen from England, and maids from Ireland.

In her book, "Maid as Muse," Murray explores the relationship between Dickinson and her staff.

"Emily Dickinson isolated herself from her peers, the wealthy leading families of the town as she got older, but the poor community was in and out," Murray says. "The servants' children were running her errands, taking her letters around the neighborhood. She was rewarding them with pieces of cake. The world came to her."

For the last 17 years of her life, Dickinson shared her kitchen with Margaret Maher, an Irish immigrant. Dickinson wrote her poems while cooking with Maher.

She stored them in her maid's trunk, trusting Maher to keep them safe. This everyday interaction, Murray says, changed the way Dickinson felt about poor people, especially those coming from Ireland.

"When she was much younger, she actually made rather hateful comments about Irish immigrants that were pouring into the country, escaping famine conditions in Ireland," she explains. "Yet, at the end of her life, in an incredibly telling gesture, in a funeral that she scripted before her death, she picked six of the family's workmen, laborers, gardeners and stable hands to be her pallbearers. That was a shocking thing to her family and to neighbors."

Lasting influence

Murray says the presence of domestic servants not only allowed Dickinson to flourish as a writer but also influenced her literary voice.

"First of all, having a maid made it possible for her to write," she says. "Her writing really jumps in a huge way when a permanent maid is in the kitchen. She goes from writing no poems to writing almost a poem a week. In terms of language changes, what really surprised me was how she really enfolded some of that language of her writing."

She points to the poem, 'It was not death, for I stood up', as an example.

It was not Death, for I stood up,

And all the Dead, lie down-

It was not Night, for all the Bells

Put out their Tongues, for Noon.

It was not Frost, for on my Flesh

I felt Siroccos- crawl- …

"That poem and that grammatical structure, it is classically the way people in Ireland speak English," says Murray.

The voice of Dickenson's African American servants is also heard in her writings.

Promise This-When You be Dying-

Some shall summon Me-…

"And that way in which she says 'when you be dying', that's so classically the way African Americans structure their sentences, with that interesting use of 'be,'" says Murray.

"Maid as Muse" author Aife Murray says writing her book was a way for her to give credit where credit is due — to the unsung men and women whose language and culture enhanced the work of one of America's best-loved poets.