Each day brings new reports of heightened Russian military activity in Syria. For more than four years, Russia has suggested it was open to a political solution to the crisis in Syria, but by expanding military operations there, it has sent a clear signal to the West that dialogue is no longer an option.

Russia’s defense minister reassured the United States its actions are "defensive in nature." For the moment, the U.S. has accepted that explanation. Secretary of State John Kerry told reporters Tuesday that Russia’s military buildup "represents basically force protection."

But some analysts aren't buying Russia’s explanation and cite a variety of reasons why they believe Russia is in Syria for the long haul. They’ll be paying close attention to what Russian President Vladimir has to say in a speech to the United Nations Monday.

Location is everything.

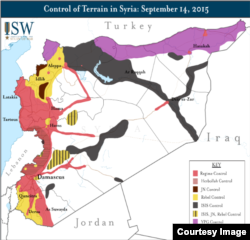

The Syrian government of Bashar Al-Assad controls, at best, 20 percent of the country, according to Christopher Harmer, a senior naval analyst with the Institute for the Study of War’s Middle East Security Project.

"Russia really only needs the coastline and the capital, Damascus. Who cares about the desert to the east," Harmer said.

The key to nearly everything Putin does, said Harmer, lies in remarks he made a decade ago, when he called the collapse of the Soviet Union "the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century."

"Putin wants to reestablish Russia as the second superpower in the world behind the United States. But in order to do that, it has to have a worldwide-deployable navy," said Harmer. "And in order to have a worldwide-deployable navy, you’ve got to have foreign bases."

After the fall of the Soviet Union, Russia lost all of its former foreign military bases, save for Tartus, a small depot on Syria’s Mediterranean coast.

Tartus allows Moscow to maintain a presence in the Mediterranean, giving it access to its sole remaining Middle East ally and allowing it to possibly cultivate new ones.

"Russia wants to maintain a role in the Israeli-Palestinian peace process, so having some influence in the region is important for that," said Dmitry Gorenburg, a Harvard University expert on Russian military reform. "In addition, following the return of the military government in Egypt, they've been trying to develop ties there in terms of both arms sales and political influence."

The Mediterranean also offers Russia access to the Red Sea through the Suez Canal and the Atlantic, via Gibraltar. And it allows Russia to protect critical shipping lanes from the Black Sea.

The Kremlin’s escalation in Syria coincides with the Iran nuclear deal – and normalized relations between Iran and the West. It also follows a visit to Moscow by Iran Quds Force commander Qassem Suleimani.

"Given the changing dynamics in the Middle East, Russia may be trying to increase its influence and form a strategic coalition with Iran," said Kilic Bugra Kanat, an assistant professor of political science at Penn State Behrend.

"And improving the relationship and coordinating actions with Iran on the ground in Syria may actually increase its influence projection capability across the region."

Invested in Syria

Moscow and Damascus established economic relations in the 1950s. When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Damascus still owed Moscow about $12 billion in loans it couldn’t afford to pay back. Russia forgave about three-quarters of the debt. In exchange, Syria agreed to pay off the balance in 10 annual cash payments, to purchase Russian weapons and give Russian companies preferential access to its oil.

The Moscow Times valued Russian exports to Syria in 2010 at more than $1 billion and private investments in Syria’s infrastructure, energy and other industries at about $20 billion.

"So if Assad steps down from power, those contracts would fall through," said Anna Borshchevskaya, a fellow at the Washington Institute who focuses on Russia's policy in the Middle East.

While this isn’t enough to trigger an economic collapse, it could dent an economy suffering from low oil prices and Western sanctions. And that, in turn, could spell trouble for Putin ahead of parliamentary elections in 2016 and a presidential election in 2018.

Putin’s popularity in Russia soared after he annexed Crimea in March 2014. Taking a more active role in Syria could distract the population’s attention away from higher prices and lower living standards.

The view from Moscow

Analysts and policymakers in Moscow are offering the Russian public a different explanation for the uptick in military activity in Syria.

It’s actually the West that is looking to take military action in Syria, Yevgeny Satanovsky, president of the Moscow-based Institute of Middle Eastern Studies, recently told the Moscow Times. Russia, he said, is merely looking to prevent a repetition of what happened in Libya.

"Then-President Dmitry Medvedev trusted the West to handle it [Libya] and we now see a country in ruins,: Satanovsky said.

Putin has long regretted the fact that Russia abstained from the 2011 U.N. Security Council vote enabling a no-fly zone in Libya, which resulted in the ouster of Muammar Gaddafi.

In a separate interview with Sobesednik Online last week, Satanovsky offered another excuse for Russian intervention in Syria.

"The U.S., Saudi Arabia and Qatar are trying to get rid of [Syrian President Bashar] Al-Assad so that with the support of his opponents they can build a pipeline for Qatari gas to southern Europe," Satanovsky said.

Syria as ‘honeypot’

Putin has billed the buildup in Syria as an effort to combat the Islamic State group – with or without U.S. help.

But many scholars are skeptical.

If Putin were merely there to fight ISIS, it wouldn't have sent combat planes or surface-to-air missiles, "considering that neither ISIS nor the opposition [has] an air force," said Kanat.

ISW’s Chris Harmer suggests that Russia actually benefits from ISIS' presence in Syria and Iraq.

"Syria is a ‘honeypot’ for separatists," Harmer said. Among "Chechans, Ingushetians, Dagostanis, even Georgians, there are a lot of ethnic separatists on Russia's southern border who [are] going over to fight with ISIS in Syria, and that makes life much better for Russia."

Russia would be happy, he said, if the fight against ISIS were to continue "more or less indefinitely."

As for the Washington Institute's Borshchevskaya, she cautioned the U.S. not to take the Russian military buildup in Syria calmly "because Putin perceives weakness, and if he does, he just keeps going.

"This is what he’s been doing in the last several years," she said. "He needs to perceive a strong hand and then he’ll stop.”