More is known about the surface of Mars than the sea floor of our own planet, eighty percent of which is unmapped. That’s changing, though, with the release of a new map based on untapped streams of satellite data.

The new map created by a team at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, is twice as accurate as the version produced by the US Navy 20 years ago.

“The way we’re doing that is to use satellite altimeter, a radar, to map the topography of the ocean surface, said Scripps geophysics professor David Sandwell interviewed by SKYPE.

“But now that seems sort of strange that you would map the topography on the ocean surface where you really want to get at the sea floor. But the ocean surface topography has these bumps and dips due to gravitational effects that mimic what’s on the sea floor.”

The scientists pulled data from two satellites, launched for other purposes. The European Space Agency’s Cryo-2 was in the sky to monitor sea ice and NASA’s Jason-1 studied ocean surface. This data set produced the big picture, which was combined with the much finer resolution images captured from ships equipped with multi-beam sonar. “That enables us to look at smaller scale features and also features that are buried by the sediments in the ocean basins,” said Sandwell.

Major mountains revealed

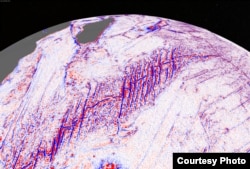

The new map shows the fabric of the seafloor as never seen before with thousands of underwater mountains, ridges where continents had pulled apart, and extinct earthquake activity buried deep under layers of sediment.

At one site where three ridges meet, the Earth’s huge thick tectonic plates appear in exquisite detail. Sandwell said it is called the Indian Ocean Triple Junction, and is one of his favorite spots in the ocean.

“It really displays the theoretical aspects of plate tectonics perfectly. You have three plates, the African plate, and the Indo-Australian plate and the Antarctic plate all connected at this one point in the Center of the Indian Ocean.”

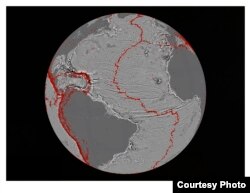

The map exposed continental connections across South America and Africa and showed evidence for seafloor spreading ridges at the Gulf of Mexico, active 150 million years ago now under layers of sediment.

Industry, military, science

Sandwell said the map is a powerful tool for fisheries conservation and for petroleum exploration. “The petroleum industry is interested in how to reconnect the continents, bringing them back together tectonically so you can map the basins on one continental margin in Africa, and use that to establish where a similar basin would be on the other continental margin in South America.”

Locating oil fields

The data also greatly improves estimates of ocean depths critical for safe navigation, military operations and science missions worldwide, Sandwell adds, “This new gravity map really provides a reconnaissance tool for planning ship board surveys. You don’t have to go out with your ship and start looking for something new, we can target that with the gravity and then go out with the ship and do the high resolution survey to really understand these features.”

Sandwell expects many more discoveries to emerge as scientists delve into the dataset. The work is described in the current issue of the journal Science.