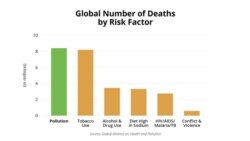

Pollution killed more than 8 million people worldwide in 2017, more than three times the global toll from AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria combined, according to the latest estimates from the Global Alliance on Health and Pollution.

More than 90 percent of the deaths occurred in the developing world, the report says.

But pollution-related deaths remain a neglected and underappreciated issue in most of the world, especially in low- and middle-income countries, the authors add.

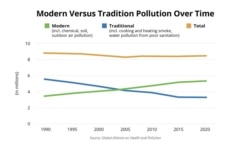

While international efforts are helping bring down the impacts of traditional pollution sources, such as poor sanitation and smoky cook fires, modern pollution from urban and industrial sources is increasing. Authorities are only beginning to pay attention, the authors noted.

The report "point(s) out that a global health crisis is, in fact, still undercounted, still under-addressed [and)] still under-resourced," acting Executive Director Rachael Kupka said.

The research updates a landmark 2017 report in the journal The Lancet by an international commission including university researchers, national health ministries, nongovernmental organizations, the World Bank and the United Nations.

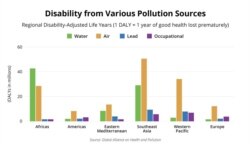

The group looked at the burden of death and disability in four categories: air, water, occupational risks and lead exposure.

India and China had the largest total number of pollution-related deaths, followed by Nigeria, Indonesia and Pakistan. The United States was seventh.

"There's countries from almost every region of the world present in that top 10 list," Kupka said. "We really are all impacted. It doesn't matter where you are."

The death rate as a proportion of the population was highest in Chad, Central African Republic and North Korea. India still ranked high, at number 10.

Air pollution was the largest category, making up 40% of the global death toll.

Pollution raises the risk of heart disease, stroke, cancer, lung disease, and other conditions that can kill as well as disable. The study says pollution accounts for more years of disability worldwide than smoking, alcohol and drug abuse, and wars and violence.

The authors say their estimates are likely an undercount. And they don't include significant pollution sources such as pesticides and mercury.

Kupka says they aim to focus on those issues in the next update in The Lancet, planned for 2021.

The good news, she added, is that pollution controls already exist that can help reduce the impacts. Authorities can adopt and enforce emissions controls for vehicles and smokestacks, provide personal protective gear for workers and require other measures already in place in many countries.

"We see a suite of problems country by country that are not unique," she said. "There are cost-effective things that countries can do, communities can do, cities can do to implement and bring down their burden of disease from pollution."