Astronomers say they have discovered evidence of the first intermediate-size black hole, created by the merger of two smaller black holes.

Up to this point, astronomers had observed black holes – super-dense regions of space with gravity so strong light cannot escape them – in only two general sizes.

There are small, or “stellar” black holes, formed when stars collapse into themselves. They range in size from three to four times the mass of our sun to tens of times the mass of our sun.

There are also are supermassive black holes that are millions, maybe billions, of times more massive than our sun. A supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy is believed to be 4 million times the mass of our sun. Intermediate-size black holes had been theorized, but never “observed” by astronomers, until now.

In a study published Wednesday in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, researchers say the observation came in the form of a signal detected in May 2019 by the National Science Foundation’s Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO). The signal was a brief but powerful gravitational wave.

One of the authors of the study, French researcher Nelson Christensen, explains that due to the nature of gravitational waves – literally, ripples in the fabric of space-time – they offer a completely different way to observe the universe, as opposed to the light that different cosmic bodies give out – in other words, what we can see through a telescope.

Christensen says light allows you to see the universe, but gravitational waves allow you to “hear” it. He compares it to a doctor seeing a patient and noting some physical symptoms that appear on the outside, but then placing a stethoscope on the patient’s chest to get a better understanding of what may be wrong.

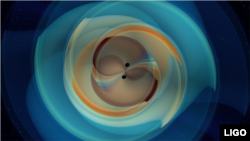

By studying the gravitational wave signal, the team discerned this ripple in the cosmic fabric was likely created by the merger or collision of two black holes, about 85 and 66 times the mass of the sun, respectively. They created a new, intermediate black hole about 142 times the mass of our sun.

Christensen said all this came from a signal that lasted about a tenth of second and resulted from an event that occurred about 7 billion years ago. But he said without that “blip” of a gravitational wave, they never would have known it had happened. He said, "There would be no way to see two black holes spinning around each other and colliding if not for gravitational waves."

Though long theorized, studying gravitational waves is fairly new. Scientists detected gravitational waves for the first time in 2015, using LIGO. Since then, the gravitational-wave detector has listened in to more of these ripples in space-time.

Christensen says each time they turn on the detectors, they “hear” interesting things. "The universe is providing us with all kinds of surprises, and that’s really wonderful.”