Mass migration and the COVID-19 pandemic have contributed to the worldwide spread of female genital mutilation, or FGM, executed on girls from infancy to puberty, say aid organizations.

Perpetrators cross borders to perform FGM in countries such as Chad, Liberia, Mali, Sierra Leone, Somalia and Sudan, where there is no legislation against the practice, according to research by Community of Practice on FGM, (CoP-FGM) an international network.

The practice dates back more than 2,000 years and is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the partial or total removal of external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital tissues, including suturing the genitalia. Among the four levels of FGM, some are banned in some countries, while other types remain legal.

“In many cases, families are aware that FGM carries a physical and mental health risk, but they have girls undergo FGM to increase their marriageability or as a way of safeguarding their chastity,” said Nankali Maksud, senior adviser of Prevention of Harmful Practices at UNICEF.

“While communities cite reasons such as religion, culture or hygiene for practicing FGM, the practice is a human rights violation and an expression of power and control over girls' and women's bodies and sexuality,” she said.

Despite bans, practice continues

FGM continues as a cultural practice to ensure a female’s virginity and decrease her sexuality so she may be more controlled, according to Maksud.

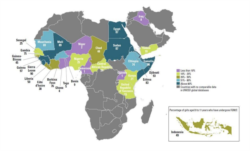

WHO estimates that 200 million girls and women alive today have undergone FGM. It has been documented in 30 countries, mostly in Africa, the Middle East and Asia, but growing migration due to war and economic adversity has increased the number of girls and women subjected to FGM.

“If a country bans FGM, they’ll usually ban a particular practice of it, so people will just do something else,” said Dena Igusti, 24, an artist and activist from New York who underwent FGM in 2006. “If that doesn’t work, they’ll go to a country that’s outwardly against it, like Western countries. But because there isn’t a focus on it, and there is this denial that it happens here, they get away with it.”

In early January, the United States tightened its ban on FGM nationally, and it is explicitly banned in 39 states. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that more than 500,000 women and girls have undergone or are at risk of undergoing FGM in the U.S.

In all member states of the European Union, FGM is criminalized. But six African nations — Chad, Liberia, Mali, Sierra Leone, Somalia and Sudan — have no laws against FGM, CoP-FGM says.

While FGM is banned in the EU, Britain and the United States, it still occurs in these areas. The private nature of the practice and the silencing of victims or their hesitation to come forward continue to make FGM challenging to track.

“Because it’s being brought to other places, the thought of it as something that happens in a faraway country doesn’t matter, because if you know someone who can do it, they’ll do it,” Igusti said. “There isn't protection here. There are legal protections, but it doesn't really matter.”

Some parents travel back to their home countries to administer FGM to their children. Igusti underwent FGM while in Indonesia visiting family.

“When it happened, it was kind of out of nowhere,” Igusti said. “My aunt said that we were going to the supermarket, but it was a completely different route. It happened in a way that was painful. I couldn’t walk for a couple of days, and I had gauze stuck in me.

“There’s the physical pain of it, but there’s also the threats of what can happen afterwards. For me, it was always the threat of getting cut again.”

Anecdotal evidence shows that when families migrate outside practicing communities, the pressure to conform still compels them to cut their daughters in secret or take them back home, Maksud said.

“Discriminatory gender norms, poverty, low levels of education, lack of access to services, poor governance and humanitarian crises may all still lead to girls being cut, even following migration,” she said.

Intervention by international organizations to end FGM has been disrupted by COVID-19 lockdowns and travel restrictions, the U.N. Children's Fund reported in February. Over the next decade, 2 million additional women and girls may undergo this procedure as a result of halted outreach and school closures, the report said.

“Before the pandemic, there were educational programs,” said Ann-Marie Wilson, founder and executive director of 28 Too Many, an anti-FGM advocacy group. “Either the funding has stopped for some of the programs, the people delivering the programs have gone away, or the girls aren’t able to access it anymore because of school closures.”

Without checks on girls in schools, many have been sent out to work, married off by their parents or sent to work in the sex industry, said Wilson.

Wilson said her organization and others like it have had difficulty continuing their FGM intervention programs during the pandemic because of a lack of funding. The group received most of its funds through in-person events. In the first quarter of 2021, 28 Too Many’s income was down by a quarter, according to Wilson.

“We’d like to make sure that we do make it through this pandemic and carry on to the future, expanding our work and seeing it into the future,” Wilson said. “We want to work until there is nobody left who has FGM and is vulnerable.”

UNICEF adapted its FGM intervention programs to accommodate social distancing during the pandemic by switching to digital media platforms, conducting door-to-door campaigns and conducting community dialogues, according to Maksud.

In 2019, the U.N. called for action to eliminate FGM globally by 2030. But with intervention tactics halted by the COVID-19 pandemic, this goal may be out of reach.

“Even before COVID-19 upended progress, the Sustainable Development Goals’ target of ending female genital mutilation by 2030 was an ambitious commitment,” said the report, written by UNICEF Executive Director Henrietta Fore and Natalia Kanem, executive director of the U.N. Population Fund (UNFPA). “Far from dampening our ambition, however, the pandemic has sharpened our resolve to protect the 4 million girls and women who are at risk of female genital mutilation each year.”