The bells are tolling in the villages of the north Italian region of Lombardy, registering yet another coronavirus death.

North Italy has suffered epidemics before, albeit much more deadly contagions in the 17th and 18th centuries, which left more than 300,000 dead. But Italians never thought they would encounter again a contagion powerful enough to test their country to its limits.

Opinion polls suggest that more than 60% of Italians approve of the government lockdown. But cooped up in their homes for a second week, Italians are wondering how many more times the bells will toll sounare a morto (song of death). And how long the country will remain at a standstill because of a virus that first appeared nearly 9,000 kilometers away in a Chinese city most had never heard of.

The Italian government, like its pre-industrial forerunners, has turned to the use of quarantines, first used by Venice in the 14th century to protect itself from plague epidemics.

Quarantining was at the heart of a disease-abatement strategy that included isolation, sanitary cordons and extreme social regulation of the population. Without a vaccine — or as yet effective pharmaceutical therapy for those who suffer severe illness — there’s not much else to do, as Italy’s neighbors and the United States are also discovering.

Hand-painted banners with the slogan, “Everything will be alright,” have started to appear in Italian cities. But many worry about the likely duration of the war against an invisible killer, and what the long-term consequences will be for their livelihoods and their country.

They aren’t the only ones in Europe asking the same questions.

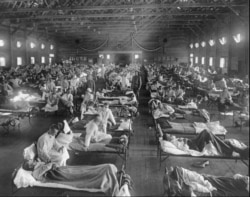

As scary, surreal and disruptive as it is now, the long-term political and economic consequences of the biggest public health challenge the continent has faced since the 1918 Spanish flu are likely to be huge.

Aside from quarantining, the past also has some possible lessons for Europe about how infectious diseases can leave a long-term imprint, say historians. They say plagues and pestilence have reshaped countries before, changing politics, contributing to instability, retarding economic development and altering social relations.

“Plague caused a shock to the economy of the Italian peninsula that might have been key in starting its relative decline compared with the emerging northern European countries,” noted Italian historian Guido Alfani in an academic paper on the impact of the 17th century plague.

In England, the long-term effects of the medieval Black Death were devastating and far-reaching, according to historian Tom James, with “agriculture, religion, economics and even social class affected. Medieval Britain was irreversibly changed,” he wrote in a 2017 commentary for the BBC. Historians say it reordered England’s social order by hastening the end of feudalism.

The Spanish flu epidemic, which killed tens of millions of people worldwide, including 500,000 Americans, affected the course of history — it may have contributed to the Western allies winning World War I, say some historians. German General Erich Ludendorff thought so, arguing years later that influenza had robbed him of victory.

And it even affected the peace, argued British journalist Laura Spinney in her 2017 book “Pale Rider,” which studied the Spanish flu. Among other things, Spinney said the flu may have contributed to the massive stroke U.S. President Woodrow Wilson suffered as he was recovering from the viral infection.

“That stroke left an indelible mark both on Wilson (leaving him paralyzed on the left side of his body) and on global politics,” Spinney wrote. An ailing U.S. president was unable to persuade Congress to join the League of Nations.

Historians and risk analysts caution that as no one knows how COVID-19 will play out — what the death toll or economic costs will be, or how well or badly individual governments may perform — they are sure it will leave an indelible mark.

Much of the impact of past contagions was due to demographic crises left in their wake — high death tolls caused social dislocation and labor shortages. Even worst-case scenarios suggest the coronavirus won’t cause a demographic crisis. But shutting down economies will have long-term ramifications, possibly a recession or depression, and will likely spawn political change.

“While the health challenges and economic consequences are potentially devastating, the political consequences are harder to foresee but might be the most long-lasting,” said John Scott, head of sustainability risk at the Zurich Insurance Group.

“Voters may not be kind to politicians who fail in their basic duty to protect citizens,” he said in a note for the World Economic Forum.

For all of Europe’s political leaders and ruling parties, regardless of ideology, the pandemic and its economic fallout risks driving them from office if they’re seen to have bungled.

Many have already been forced into policy reversals. Britain’s prime minister, Boris Johnson, who outlined Monday the biggest set of changes in the daily lives of Britons since World War II, has made large U-turns in the space of days.

This week, he made his biggest reversal following new modeling by disease experts at London’s Imperial College, which suggested that without a national shutdown the death toll would exceed 250,000.

In Europe, member states have been breaking with Brussels over border controls. European Union officials insisted that national governments should not close borders or stop the free movement of people within the so-called Schengen zone.

Last week, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen warned that “each member state needs to live up to its full responsibility, and the EU as a whole needs to be determined, coordinated and united.”

Her advice has been ignored, with countries across the continent closing their borders.

Some believe that the Schengen system of borderless travel will never be fully restored after the virus has been suppressed or run its course.

Luca Zaia, governor of the Veneto region, one of Italy’s worst-hit areas, told reporters that Europe’s borderless zone was “disappearing as we speak.”

“Schengen no longer exists,” he said. "It will be remembered only in the history books.”

He and others believe as the crisis deepens, member states will take other unilateral actions, setting the stage for a patchwork of national policies that will erode European unity and set back the cause of European federalism.

The Economist magazine also suggested last week that the coronavirus will play more to the agenda of populists, who decry globalization and have lamented the weakening of nation states.

But other observers say COVID-19 could have the reverse effect by trigging an uptick in multilateralism and greater cross-border solidarity, much as the Spanish flu prompted the ushering in of public health care systems and the first international agencies to combat disease.

How the fight goes against the virus is one thing. Another is how Europe copes with the likely economic slump that follows, and a debt crisis that might be triggered, analysts say.

That, too, will reshape national and continental politics, much as the 2008 financial crash shattered the grip of mainstream parties on European politics.