Reports one day suggest the respiratory outbreak in China might be slowing, the next brings word of thousands more cases. Even the experts have whiplash in trying to determine if the epidemic is getting worse, or if a backlog of the sick is finally getting counted.

Continuing questions about the new virus are complicating health authorities’ efforts to curtail its spread around the world. And the United States is taking the first steps to check that cases masquerading as the flu won’t be missed, another safeguard on top of travel restrictions and quarantines.

Here’s what you should know about the illness:

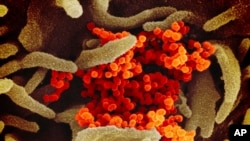

What is the new virus?

It’s a never-before-seen type of coronavirus, a large family of viruses that affect both animals and people. Some types cause the common cold. But two other types have caused severe disease outbreaks before: SARS, or severe acute respiratory syndrome, in late 2002, and MERS, or Middle East respiratory syndrome, which first appeared in 2012.

The World Health Organization officially named the new illness COVID-19, reflecting that it’s a new coronavirus that emerged late last year. Common symptoms include fever, cough and shortness of breath. While serious cases can turn into pneumonia, most patients appear to have a fairly mild illness.

How fast is the outbreak growing?

There’s some confusion about that. China’s tally reached more than 66,000 cases Saturday, a huge increase from earlier in the week. Why? Chinese health authorities say they changed how they are counting. Instead of waiting for a virus test to confirm someone’s diagnosis — there’s a huge testing backlog — they’re now counting patients on the basis of their symptoms and lung X-rays.

The WHO isn’t sure that’s a good idea and wants to make sure people with flu or some other respiratory infection aren’t getting caught in the mix.

Elsewhere, fewer than 600 cases have been reported outside of China — in other parts of Asia, Europe, the U.S. and Canada. The first case in Africa was reported Friday, in Egypt. Most involved travelers from China and people who came into close contact with them.

Is the quarantine working?

China has put 60 million people in its hardest-hit cities under lockdown, an unprecedented response. Without a good count of how many people are sick, and when they got sick, it’s hard to tell if it’s working.

That’s different from typical quarantine measures, which try to target people who may be at risk — those who were in China’s hot zone or who came into contact with another patient anywhere else in the world. That’s a way to buy time for health authorities to prepare if the virus starts to spread more widely.

But how to quarantine large numbers of people is a difficult question. The Diamond Princess cruise ship, which has the largest cluster of infections outside China, was quarantined in Japan with more than 3,500 passengers and crew. Experts have questioned if the close quarters have contributed to the spread. U.S. officials said Saturday it would evacuate its citizens from the ship and bring them to quarantine stations on Air Force bases in California and Texas.

In the U.S., about 600 people evacuated from hard-hit Hubei province in central China are still in quarantine at several military bases, apart from other people on the base but with some room to roam. For 14 days — what scientists believe to be the incubation period — they are checked for symptoms and tested if they show any.

As of Saturday, there were 15 cases in the U.S., including three of the evacuees.

Could the virus be spreading silently in other places?

In the U.S., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is starting a new effort to spot if that happens — by adding coronavirus testing to the network that normally tracks influenza. When a patient sample tests negative for flu, lab workers next will check it for the new virus.

The extra tests will start in public health laboratories in five cities: Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, Chicago and New York. But the surveillance will be expanded around the country in the coming weeks, said CDC’s Dr. Nancy Messonnier.

How does infection spread?

Like typical respiratory viruses, it spreads mostly through droplets from coughs and sneezes. What about surfaces like doorknobs touched by that person blowing his nose? If the next person touches their own mouth, nose or eyes, infection is possible, as with the flu, but specialists don’t think the virus can survive on surfaces for very long. Regular hand-washing is a good way to avoid getting sick from any virus.

What about treatments and vaccines?

The hunt is on for both. Currently, people who are seriously ill get standard pneumonia care including fluids and oxygen. In China, scientists are testing some medicines developed for other viruses to see if they might tamp down this one.

Several research groups are on the trail of possible vaccines, and one being developed by the U.S. National Institutes of Health might begin first-step safety tests in people as early as spring. But specialists stress it would take far longer — best case scenario a year — to ready a vaccine for widespread use.