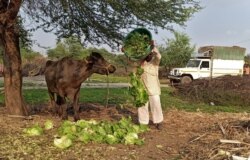

Summer fruits and vegetables have ripened, a bumper crop of wheat is ready for harvest in India, but hobbled by severe labor shortages, transport bottlenecks and plummeting demand due to a nationwide coronavirus lockdown, millions of farmers are staring at huge losses.

The setback caused by the COVID-19 pandemic will plunge the country’s struggling rural economy that supports nearly half its population into further distress, according to farm economists.

In Haryana, a lush farm state in the north, Kamal Yadav was just beginning to pluck a bountiful harvest of cucumbers and bell peppers on a two-hectare plot when the lockdown was announced two weeks ago. “Suddenly there were no buyers. Big retailers, restaurants and hotels all closed down and household demand dipped drastically because many fear that vegetables are handled by too many people.”

Yadav distributes some every day to a local charity that feeds the poor but much of his crop is rotting. “I can’t pluck all of it because I cannot spend on labor for something that will not fetch me any profit,” he says, as he writes off a crop that he expected would bring in about $20,000.

Now he is scrambling to arrange labor that is in short supply to harvest the wheat he grows on eight hectares.

The coronavirus pandemic that prompted the government to announce a strict three-week shutdown starting March 25 coincided with the country’s peak summer farm season, when crops are harvested and sold. It also came at a time when most farmers were set to reap bumper harvests after good monsoons last year.

Although farming has been declared an essential service and agriculture markets are exempted from the lockdown, a shuttered economy has left farmers facing huge challenges.

The supply chain has been badly hit -- buses and train services have been suspended and trucks face hurdles in moving across state borders due to strict checks.

In the western Maharashtra state, Asia’s largest onion trading market in Lasalgaon is struggling to transport the freshly harvested crop across the country or ship it to countries like Malaysia and in the Middle East. The reason: tens of thousands of daily wagers who came from neighboring states fled to their villages in panic in the wake of the unprecedented lockdown.

“We are crippled with shortages of labor that used to unload produce and pack it. Procuring passes that are needed for people to leave their homes for work is a challenge because we use temporary labor,” says Kshitij Jain, an onion trader in Lasalgaon. “Then we are facing shortages of packing material, which came from another state. Truck movement is not smooth.”

Jain says even local laborers are hesitant to step out of their homes amid repeated messages about maintaining a social distance – many are wary of being in crowded farm markets where hundreds usually work close to each other.

Such stories are being echoed by farmers across the country. Grape farmers, whose crops usually fetch $1.50 per kilogram from exporters, are now selling their product for less than half the price in local markets. “I managed to pluck my crop with the help of 10- to 15 college students whom I knew. We all wear masks, use sanitizers and then harvest the grapes,” says Shriram Gawade, who grows grapes on his two-hectare farm near the western city of Pune. “My friends and family all helped me arrange transportation.”

Gawade says with storage facilities in his region already overflowing, he has had no option but to take whatever prices are offered to him.

India is the world’s second largest producer of fruits and vegetables which have taken the greatest hit as prices have plunged.

“When the government announced the lockdown, perhaps they did not visualize that agriculture is not an industry where you pull down the shutters today and restart in a few weeks, “says Devinder Sharma, a food economist. “The crop will ripen, the cow will give milk, harvesting has to be done at a proper time.”

The government is now scrambling to help farmers sell their wheat crop, which is set for record production and is being harvested.

At least two states, Punjab and Haryana, have expanded the number of markets from where it will be picked up to prevent crowding and ensure that social distancing, seen as critical in preventing the spread of the coronavirus, can be maintained.

There is a silver lining. While the rural economy will reel from the losses, India’s food security is unlikely to be affected – the country maintains huge buffer stocks of wheat and rice and its granaries are overflowing with nearly 60 million tons of food grain.

“We are blessed,” says Sharma. “At a time when most countries across the globe are racing to protect food stocks, we have abundant food grains and enough supplies to give to those who need it in the country.”

Those stocks will come in handy at a time when millions of daily wagers are without jobs and will need government support in the months ahead. The government has announced a $22.6 billion package to provide rations such as rice, wheat and lentils and cash transfers to 800 million people; but economists say much more will be needed to alleviate the widespread distress.