Almost all American presidents have faced a crisis while in office, whether it’s a political scandal, natural disaster, economic calamity or terrorism. But not all have the misfortune of having to deal with epidemics and pandemics. Here are some of them and how historians view their performance.

Woodrow Wilson – Spanish flu

President Woodrow Wilson faced the influenza pandemic of 1918-19 that killed 20 million to 50 million people around the world while the United States was fighting in World War I.

“Even though President Trump has talked about being at war with the pandemic, in the case of Wilson and the Spanish flu, the United States really was at war,” said Thomas Schwartz, professor of history at Vanderbilt University.

The war was the reason Wilson’s administration downplayed the crisis, from the moment the outbreak began until it eventually killed 675,000 Americans.

“Woodrow Wilson never made a public statement of any kind about the pandemic,” said John M. Barry, professor at the Tulane University School of Public Health and author of The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History.

“It was an indication of Wilson’s intense focus on the war – that was all he cared about,” Barry said.

Like Britain, France and Germany, the U.S. kept the outbreak secret because it didn’t want to show weakness to the enemy. At the height of the outbreak, Wilson sent troops abroad packed into ships that were “cauldrons of virus transfers,” said Max Skidmore, political science professor at the University of Missouri-Kansas City and author of Presidents, Pandemics and Politics.

Eventually a quarter of all Americans became infected, including several who worked at the White House. Many historians believe Wilson himself fell ill. Barry said that during negotiations ahead of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles in Paris, Wilson had “103, 104 fever, violent coughs, and other symptoms that were unique to the 1918 virus.”

As states and cities began to order what we now know as social distancing – closing businesses and schools, banning public gatherings – Wilson’s administration continued to downplay the pandemic. Spain, a neutral party in the war, was the only country that reported casualty numbers accurately, hence the name Spanish flu, even though the flu did not originate there.

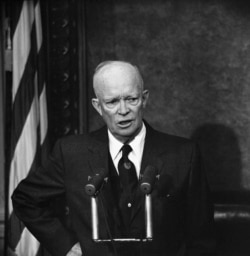

Dwight Eisenhower – Asian flu

The H2N2 virus was first reported in Singapore in February 1957 and reached the United States that summer.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower was aware of the impending pandemic, Skidmore said, but he initially refused to start a nationwide government-supported vaccination program. “He had faith in the ability of free-market vaccines to take care of the impending crisis,” Skidmore said. “And as a result, the death rate was perhaps about doubled what it might have been otherwise.”

In August 1957, Eisenhower asked Congress for $500,000 in funding and authorization to shift an additional $2 million, if needed, to fight the outbreak. He set a goal of 60 million doses of vaccines, enough to vaccinate a third of the population, around 171 million at that time. By early November, about 40 million doses had been given, and the pandemic began losing steam.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated the number of deaths from H2N2 at 1.1 million worldwide and 116,000 in the United States.

Gerald Ford – Swine flu

Leaders are often faulted for downplaying crises, but Gerald Ford was accused by some of overreacting.

Not long after a soldier died of a new form of flu in February 1976, the U.S. secretary of health, education and welfare announced that the virus could turn into an epidemic by fall.

Scientists at the CDC thought it could be even deadlier than the 1918 flu strain. To avoid an epidemic, the CDC said at least 80 percent of the U.S. population would need to be vaccinated, leading Ford to sign emergency legislation for the National Swine Flu Immunization Program, in mid-April. Within a few months, close to 50 million Americans were vaccinated.

Ford took action quickly, but issues with the vaccine caused more problems in the end, Vanderbilt’s Schwartz said. Hundreds of people came down with Guillain-Barre syndrome, a rare neurological disorder, after getting the flu shot.

“Ironically,” Skidmore said, “it was the sophistication of the government's own monitoring system that led them to identify those cases and associate them with the vaccine.”

While Ford demonstrated the government’s efficiency in marshaling resources, his massive vaccination program, on top of other political blunders, contributed to Ronald Reagan’s attempt to wrest the Republican nomination from Ford in 1976. Ford lost to Democrat Jimmy Carter later that year.

“The general consensus is that he was overreacting,” said Skidmore, who nevertheless lauded the president’s better-safe-than-sorry approach. “He seemed to be convinced, and I think correctly so in retrospect, that it would be far better to have a vaccine and no pandemic, then to have a pandemic and no vaccine.”

By the time immunizations began in October, a large outbreak had failed to emerge, and swine flu became known as the pandemic that never was. The experience contributed to the hesitance of some Americans to embrace vaccines, even now.

Ronald Reagan – the AIDS crisis

The Reagan administration has been criticized for not taking AIDS seriously and for allowing the stigmatization of gay men in America. Audio recordings of press conferences in the early ‘80s reveal President Ronald Reagan's press secretary joking with journalists about the epidemic using the term "gay plague."

Reagan’s approach was “certainly not a model for future presidents,” Schwartz said. Part of this is because in the early phase of the outbreak, most of the victims were either homosexuals or drug addicts, groups outside Reagan’s conservative coalition.

Despite American gay men showing signs of what would later be called AIDS as early as 1978, Reagan did not publicly use the word “AIDS” until September 17, 1985, well into his second term.

“Reagan simply failed to recognize the severity of the AIDS epidemic,” Skidmore said. Reagan also believed that government was the problem, not the solution, so his predisposition was to diminish its role even in crises, Skidmore added.

In April 1987, Reagan declared AIDS “public health enemy No. 1.” He allocated $766 million for AIDS research and education, to be increased to $1 billion in fiscal 1988. But he advised sexual abstinence instead of methods of protection.

“Let's be honest with ourselves,” Reagan said. “AIDS information cannot be what some call 'value neutral.' After all, when it comes to preventing AIDS, don't medicine and morality teach the same lessons?”

By the end of Reagan’s presidency in 1989, the United States had suffered 89,343 AIDS-related deaths.

George W. Bush – AIDS crisis and SARS

President George W. Bush has received applause from both Republicans and Democrats for the commitment he made to help fight HIV/AIDS globally and particularly in Africa.

His success contrasted with the mixed legacy of his father, George H.W. Bush. During his time in office, the elder Bush signed two important pieces of legislation — the Americans with Disabilities Act, which protected people with HIV and AIDS from discrimination, and the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency Act, which provided funding for AIDS treatment. But some see a lack of urgency on the part of the administration and criticize Bush for refusing to change a policy that blocked people with HIV from entering the United States.

In 2003, the George W. Bush administration created the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), an initiative to address the global epidemic.

“PEPFAR was probably one of the best things in his presidency,” Barry said. “It got pretty much universal applause.”

Since its inception, PEPFAR has provided more than $80 billion for HIV/AIDS treatment, prevention and research, making it the largest global health program in history focused on a single disease. It is widely credited with having helped save millions of lives, primarily in sub-Saharan Africa.

In April 2003, after an outbreak in Asia, Bush signed an executive order adding severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) to a list of communicable diseases that can lead to people being involuntarily quarantined. Eventually more than 8,000 people worldwide became sick with SARS, and 774 died during the 2003 outbreak. In the United States, only eight people had laboratory evidence of the infection.

In 2005, the Bush administration created the National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza, which called for the federal government to maintain and distribute a national stockpile of medical supplies in the event of an outbreak, and an infrastructure for future presidents to learn from and build upon in dealing with their own pandemics.

Barack Obama – H1N1, Zika and Ebola

A few months into President Barack Obama’s first term in 2009, reports started coming in about H1N1, or swine influenza, which was detected first in the United States and spread quickly around the world.

According to the CDC, the first case was reported April 15, 2009. The Obama administration assembled a team and declared H1N1 a public health emergency on April 26, six weeks before it was declared a pandemic and before any deaths had been recorded in the U.S.

The Obama administration “geared up as soon as the virus surfaced,” Barry said. “They were 100% all in, both in terms of scientific research and trying to generate vaccines and in public health measures.”

Six months after that initial declaration, with more than 1,000 American lives lost, Obama declared swine flu a national emergency.

The CDC estimated that from April 2009 to April 2010, there were 60.8 million cases of swine flu and 12,469 deaths from it in the United States. The World Health Organization declared an end to the pandemic on August 10, 2010.

Four years later, Obama faced another crisis – the 2014-16 Ebola outbreak that killed more than 11,000 people in West Africa.

Obama activated the CDC Emergency Operations Center in July 2014 to help coordinate technical assistance, including deploying personnel to West Africa to assist with response efforts. The CDC trained almost 25,000 health care workers in West Africa on infection prevention and control practices.

Only 11 people were treated for the virus in the U.S. Yet some Republicans criticized Obama for not instituting travel bans from countries where the Ebola outbreak was pervasive.

Obama fought a different virus on the home front – Zika, a virus transmitted by mosquitoes. The 2015 Zika outbreak was first recorded in Brazil, and by 2016 about 40,000 cases were reported in the U.S. The Obama administration requested $1.9 billion in emergency federal funding to fight the virus in February 2016, $1.1 billion of which was approved by Congress that September.

In 2015, Obama's national security adviser, Susan Rice, created the Global Health Security and Biodefense unit, a team responsible for pandemic preparedness under the National Security Council, a forum of White House personnel that advises the president on national security and foreign policy matters.

In May 2018, during the presidency of Donald Trump, the Global Health Security and Biodefense unit was disbanded. Its leader left the administration, and some of its members were merged into other units within NSC.

Lessons learned

Historians say that in the face of public health crises, presidents who are informed, focused, organized and transparent are most likely to be successful.

Skidmore, of the University of Missouri-Kansas City, said American presidents can learn from their predecessors, particularly in establishing strong coordination between the federal government and states, and ensuring the private sector is fully engaged. Skidmore said the Obama administration greatly benefited from George W. Bush’s National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza, a plan that spanned every department of the federal government, every state and broad swaths of the private sector to stockpile antiviral medications and provide scientists resources to develop vaccines.

Schwartz, of Vanderbilt, and Barry, of Tulane, said that leaders must be optimistic and provide hope. But more important, they must be transparent, both to prevent unfounded information from spreading and to create the credibility that will encourage people to follow guidelines instead of being skeptical of their government.