When Cameroonian medical doctor Conrad Tankou won the top health award at an international innovation competition, he breathed a sigh of relief.

Winning the $25,000 prize at the Next Einstein Forum in Kigali, Rwanda, last week was the culmination of years of struggle.

“Sometimes, I doubted I would get this far,” 30-year-old Tankou said. “We’ve come a long way. It’s the first time this project is actually getting any recognition. So, many people didn’t believe in it in the beginning, and up ‘till now, some people are still doubting.”

WATCH: Next Einstein Forum

Tankou, a general practitioner based in Bamenda in northwestern Cameroon, led a team to invent what he calls GIC Med. It’s a portable digital microscope that connects to a smartphone to remotely scan for cervical cancers for medical analysis. About 7,000 cases of cervical cancer are discovered yearly. The disease is the second most frequent cancer among women in Cameroon.

While creating his technology and seeking support, Tankou said he faced resistance from medical professionals. There was also the challenge of an unreliable internet, which he said is necessary for today’s scientists. Only about 25 percent of Cameroon’s population has Internet access, and the connection is prone to blackouts.

Some of the blackouts are political. The Cameroonian government has periodically shut down the internet in Anglophone regions, including Bamenda, where citizens are accusing the Francophone-dominated government of marginalizing English-speaking people. One blackout last year reportedly lasted a record 93 days.

Tankou said he also had to confront what he described as a “sad” mindset.

“There is mindset here in Africa where we don’t believe in the ability of another African to solve our problems. We have doubts that solutions in Africa can come from an African. We expect solutions to come from the West,” he explained.

Tankou is determined to make his technology available to help save lives. He said the Next Einstein Forum (NEF) was the best platform to showcase his innovation.

Africa has been left behind

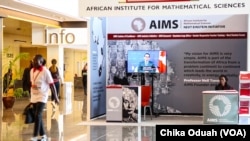

Created by the African Institute for Mathematical Sciences (AIMS) with the underlying belief that “the next Einstein will be African,” NEF brings together the largest gathering of African scientists to discuss innovations in climate change research, health and data technology to solve local problems. The first was held in Dakar, Senegal, in 2016, where nearly 1,000 people convened.

More than 1,600 people gathered in Rwanda last week for the second edition. Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame opened the forum.

"For too long, Africa has allowed itself to be left behind, but that’s starting to change, as we see in the important work on display at this forum," Kagame said in his opening address.

Kagame’s government has heavily pushed education in science-based fields.

According to the World Bank, less than 2 percent of total global scientific research output comes from Africa. Some of the barriers are cultural.

“There’s also this old mentality prevailing in Africa where elders are respected more than youth. So, young people are not always supported. They have to find their own way,” said Joel Gasana, who is in his final year as a medical student at the University of Rwanda.

Gasama received $5,000 from an organization affiliated with the U.S. Agency for International Development. The Nigeria-based Tony Elumelu Foundation awarded him another $5,000 grant.

The mobile app he created to help HIV patients keep up with their treatments lost to Tankou in the competition.

Rachel Sibande, a Malawian scientist who devised a tool to generate electricity from maize (corn), won in the “climate smart” category.

She noted that 90 percent of Malawi’s population is not connected to the national power grid.

Sibande, 32, said Africa is left behind when it comes to scientific research and innovation, due to a lack of funding, lack of opportunities for collaboration, few incentives and an educational system that does not enable students to think critically.

Abdoulaye Diallo, whose artificial intelligence project won in the “deep tech” category, said he did not think he would have been able to develop his technology in his native Guinea. He created it in Canada, where he has access to world-class labs as a university professor. But he admits that many scientists in Africa do not have such opportunities.

Steps of progress

These days, several initiatives are springing up to boost research-based science in Africa. A report jointly issued by the World Bank and Elsevier, the world’s largest publisher of academic journals, revealed that between 2003 and 2012, African researchers more than doubled their production of research in the science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) fields.

At this year’s NEF, Elsevier and AIMS announced the launch of The Scientific African, a first-of-its-kind pan-African, peer-reviewed, open-access publishing journal dedicated to amplifying the global reach and impact of African research. News of the launch has generated positive buzz on social media over the past few days.

Scientists in Africa have long felt they were at a disadvantage simply by being in Africa, but NEF hopes to change that. The next edition will be in Nairobi, Kenya, in 2020.

NEF is setting up a $1 million fund to encourage scientific breakthroughs in Africa.