Principals, superintendents and counselors are filling in as substitutes in classrooms as the surge in coronavirus infections further strains schools that already had been struggling with staffing shortages.

In Cincinnati, dozens of employees from the central office were dispatched this week to schools that were at risk of having to close because of low staffing. The superintendent of Boston schools, Brenda Cassellius, tweeted Wednesday she was filling in for a fifth grade teacher. San Francisco's school system asked any employees with teaching credentials to be available for classroom assignments.

Staff absences and the omicron variant-driven surge have led some big districts including Atlanta, Detroit and Milwaukee to switch temporarily to virtual learning. Where schools are holding the line on in-person learning, getting through the day has required an all-hands-on-deck approach.

"It's absolutely exhausting," said history teacher Deborah Schmidt, who was covering other classes during her planning period at McKinley Classical Leadership Academy in St. Louis. On Thursday, she was covering a physics class.

In a school year when teachers are being asked to help students recover from the pandemic, some say they are dealing with overwhelming stress just trying to keep classes running.

"I had a friend say to me, 'You know, three weeks ago we were locking our doors because of school shootings again, and now we're opening the window for COVID.' It's really all a bit too much," said Meghan Hatch-Geary, an English teacher at Woodland Regional High School in Connecticut. "This year, trying to fix everything, trying to be everything for everyone, is more and more exhausting all the time."

Labor tensions have been highest in Chicago, where classes were canceled after the teachers union voted to refuse in-person instruction, but union leaders in many school systems have been clamoring for more flexibility on virtual learning, additional testing and other protections against the virus.

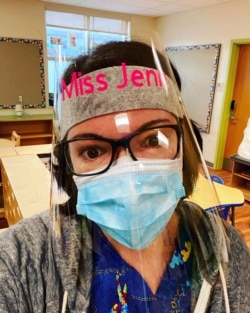

In New Haven, Connecticut, where hundreds of teachers have been out each day this week, administrators have helped to cover classrooms. When her classroom aide did not show up for work Wednesday, special education teacher Jennifer Graves borrowed paraprofessionals from other classrooms for short stretches to get through the day at Dr. Reginald Mayo Early Childhood School — an arrangement that was difficult and confusing for her young students with disabilities.

"It's very difficult to get through my lesson plans when somebody doesn't know your students, when somebody is not used to working with students with disabilities," Graves said. "Some students need sensory inputs, some students need to be spoon-fed. So it's very hard to train someone on the spot."

Even before infection rates took off around the holidays, many districts were struggling to keep up staffing levels, particularly among substitutes and other lower-paid positions. As a result, teachers have been spread thin for months, said Becky Pringle, president of the National Education Association.

"All of these additional burdens and stresses on top of being worried about getting sick, on top of being stressed like all of us are to after a two-year pandemic ... it just compounded to put us in a place that we are now," Pringle said in an interview.

Some administrators have already been helping for months in classrooms and cafeterias to fill in for sick and quarantining staff.

"We're not in love with the circumstances, but we're happy to do the work because the work is making sure that we're here for our kids," said Mike Cornell, superintendent of the Hamburg Central School District in New York, who spent time this fall on cafeteria duty poking straws into juice pouches and peeling lids off chips to fill staffing gaps.

Among the schools that went virtual this week because of staffing shortages was second grade teacher Anna Tarka-DiNunzio's school of roughly 200 students in Pittsburgh. Some taught their students despite being sick with the virus, said Tarka-DiNunzio, who was disappointed to hear some characterize staffing shortages as the result of teachers arbitrarily taking off work.

"It's not just people calling off. It's people who are sick or who have family members who are sick," she said.

The strains on schools this week might have been even tougher if not for large numbers of students being absent themselves. In New Haven, teachers say classes have been only about half full.

Jonathan Berryman, a music teacher, said some of his students haven't shown up for weeks. He worries what that will mean for the performance targets set for students and their teachers.

"Before omicron came along, there was fairly smooth sailing. Now the ship has been rocked," he said. "We get to make midyear adjustments in our evaluation system. And some I'm sure are wondering whether we should even be concerned about that academic progress piece."

Graves, who is in her 12th year of teaching in New Haven, said that she is grateful for administrators who have been helping out in classrooms and the aides who have pitched in, but that her students have struggled with the lack of consistency in staffing.

She also has been frustrated with quickly changing health protocols, and worried about the health of herself and her extended family. Most of her young students are not able to tolerate wearing masks for long stretches, and many have been coughing lately.

"This is the hardest year I've had," she said.