When a tsunami races toward shore, the best strategy for survival is to head inland to high ground as quickly as you can. But there are beach towns on coastlines all around the world where it would be impossible to do that, because high ground is out of reach, especially if the roads are buckled or jammed after a great earthquake.

Now one low-lying coastal town in Washington State is copying a strategy used in Japan to survive tsunamis: sheltering in place on a roof-top refuge.

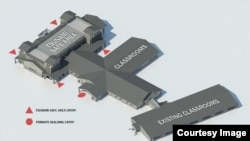

Around this time next year, Ocosta Elementary School in Westport, Washington, will have a new gym with a reinforced roof that can double as a tsunami refuge. This will be the first structure in North America purposely designed for tsunami vertical evacuation.

Standing up to a tsunami

Westport is basically one long sand spit. The elementary and high schools were built on one of highest dune ridges around. But that's only about 8 meters above sea level... and that may not be high enough in the worst case scenario of a magnitude 9.0 full rip of the offshore Cascadia earthquake fault. Models predict the subsequent tsunami would wash over pretty much everything for miles around.

Structural engineer Cale Ash of Degenkolb Engineers in Seattle took that as a design challenge, and outlined the features they built into the new gymnasium.

"The extra features would include the pile foundations, which were made a little bit larger in diameter and also deeper to make sure they could resist any scour, any washing away of the site that would happen from tsunami flow. The building is also designed to resist impact. As the water comes in, it can bring debris like logs and vehicles and other stuff."

Four outside stairways lead to a flat, concrete and steel reinforced roof capable of holding more than 1,000 people. Ash says the rooftop refuge is about 4 meters above the maximum estimated tsunami height.

Choosing vertical evacuation

"Vertical evacuation to me is never the preferable option," says geologist Lori Dengler, an earthquake and tsunami expert at Humboldt State University in California. "If you talk to any emergency manager, they are not going to want to have people isolated on top of a building possibly for days - or maybe even a week or longer."

That said, Dengler understands that sometimes the last choice is the only choice. In places like Westport and Ocean Shores, Washington, and Seaside, Oregon, she says vertical evacuation could offer the only chance of survival and should be considered.

But she stresses that a key issue whenever such an evacuation structure is built is, "is it tall enough?"

After the devastating 2011 tsunami in Japan, Dengler participated in a survey of the disaster zone that examined the performance of vertical evacuation. The Japanese coast is the only place in the world where designated vertical evacuation structures are common. The reconnaissance team heard how this saved many lives, but also noted that more than 100 elevated safe havens were overtopped by the tsunami surges on March 11, 2011.

"If a tsunami turns out to be a little bigger than expected," Dengler observed, people who evacuate inland to high ground, can continue to go up or farther inland. "But once you are on the third or fourth story of a four story building, you can't go any higher."

Creating high ground

Elsewhere, a handful of low-lying communities are planning another kind of tsunami safe haven. In Long Beach, Washington, Humboldt County, California and Padang, Indonesia, residents have proposed tall earthen mounds.

The prototype "tsunami mountain" proposed for the southwestern coast of Sumatra is designed with a park on top that could hold many hundreds of people. Like Westport, many residents in the crowded city of Padang would not be able to evacuate to high ground in the limited time they'll have after a big quake.