Until recently, Syrian refugee Eyad Zoulghena only had bad options.

The 22-year-old, forced to quit law school when he fled his homeland in 2012, could choose to keep working in a supermarket in Jordan to feed his parents and four siblings, effectively putting his future on hold. He could risk a dangerous sea journey to seek his luck in Europe. Or he could return to war-ravaged Syria.

Now a first opportunity has opened up for Zoulghena - European Union-funded college scholarships for displaced Syrians in Jordan. The pilot program includes 270 such grants now, with a promise of hundreds more in the coming months.

Zoulghena has applied, along with more than 5,000 other Syrians desperate to resume higher education they could otherwise not afford.

If he doesn't get a scholarship, “you'll see me next summer in Germany,” said Zoulghena, speaking recently at Jordan's Zarqa University where Syrians crammed lecture halls to hear more about the EU grants.

As the Syria conflict drags on, such scholarship programs signal an attempt by international donors to shift from mostly emergency humanitarian aid to long-term programs, including education and job creation in Middle Eastern host countries.

Coming up with ways to get hundreds of thousands of uprooted young Syrians back into schools and colleges, and to find employment for their parents will be central issues at Thursday's annual Syria aid conference, to be held in London.

“The scale of the crisis for children is growing all the time, which is why there are now such fears that Syria is losing a whole generation of its youth”, Peter Salama, the regional director of UNICEF, said in a statement Tuesday.

The bulk of Syrian refugees, close to 4.6 million, still live close to home, mainly in Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey and Iraq.

However, hundreds of thousands of Syrians have headed for Europe over the past year, some driven by increasingly tough conditions in regional host countries. Many say concern for their children's future is pushing them to make the dangerous trip across the Mediterranean.

The often chaotic influx has helped shift European thinking about aid in recent months; Germany's Economic Cooperation Minister, Gerd Mueller, said during a Jordan visit last week that it's “20 times more effective” to improve refugee lives in the region than it is to help them once they get to Europe.

“We want to encourage young people to make a choice here for their future,” said Job Arts, the EU's head of education programs in Jordan. "The whole risk of getting lost at sea and in Europe itself, this is a very difficult situation.”

In addition to college scholarships the EU also supports, in cooperation with the British Council, three-month language courses for 2,800 students, said Arts. Other offers include several hundred grants for vocational training and distance learning.

Still, the situation is bleak.

UNICEF, the U.N. agency for children, estimates that close to 3 million Syrian children are not in school, including 2.1 million inside Syria and more than 700,000 refugee children.

In host countries, some refugee children drop out to work and help struggling families, or because they missed too much school and can't catch up. Others are told there's no room in crowded local schools.

One of the stated goals at the London conference is to get all Syrian refugee children back to school by the end of the 2016/17 school year.

In Jordan, more than half of about 630,000 Syrian refugees are younger than 18, including 228,000 of school age, according to UNICEF.

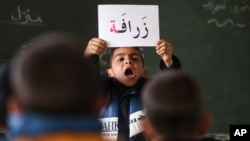

Of those, some 82,000 - or more than one-third - are not in school, the agency said. Trying to fill the gap, UNICEF runs dozens of centers across Jordan, where out-of-school children get some schooling, including the basics in English, math and Arabic.

Even for refugees who are enrolled in school, the way forward - getting into college - is filled with obstacles. Most can't afford to pay Jordanian tuition costs.

In Jordan's U.N.-run Zaatari camp for Syrian refugees, set up in 2012, school initially wasn't a priority for new arrivals. Many thought they would just be staying for a few months or were too traumatized to focus on studies.

This led to low achievement. In 2013, only four out of several dozen high school seniors passed college matriculation exams, or “tawjihi,” camp officials said.

Trying to help, UNICEF partnered with the aid group Relief International to run remedial classes for students of all ages in Zaatari and the smaller Azraq camp.

On a recent morning, more than a dozen Zaatari fifth graders attended remedial math class. Boys stepped up to the blackboard, where a teacher guided them through adding and subtracting five-digit figures.

Alaa al-Qaisi, a Relief International field coordinator, said he has seen gradual improvements.

Participation in remedial classes for high school seniors rose from 60 students in 2014 to 150 in 2015, meaning half the 12th graders are now enrolled, said al-Qaisi.

Students are more motivated because the reality of a long exile has sunk in, which means they “start looking for a future, for a good education,” he said.

The first success stories have also helped.

Eight students who passed the college matriculation exams in the previous round - all participants in the remedial program - received college scholarships, now widely seen as the best way out of a dead-end existence in the camp.

Qassem Hariri, 18, one of the eight, studies Arabic at Yarmouk University on a U.N. scholarship.

Hariri and some of his former school mates said they prefer to stay in Jordan, where they know the language and the culture. Some said they would have left for Europe had it not been for the scholarships.

Amin Nasser, 19, who took the tawjihi exam recently and hopes to study IT, said there is no way he will stay in Zaatari.

“If I don't get a scholarship and I can't go to Europe, I will go back to Syria,” he said.