At an outdoor cafe in the Saudi Arabian capital, 28-year-old Abdullah looks nervous, but says he is happy to chat with two female reporters.

As we sit down at one of the empty tables, the manager comes outside and asks us to leave. Like most places in the popular dining district, it is for men only.

If Saudi religious police drive by, it could be bad for business. The religious police are charged with enforcing rules about modest dress, and keeping unmarried or unrelated men and women from fraternizing.

A nearby restaurant manager ushers us into a separate "family section" - a place where men can sit with their wives, or women can sit together at booths surrounded by curtains. Some elders in Saudi Arabia would have been concerned that the manager allowed it, knowing none of us were related by marriage or blood.

But young people are connecting to the world through social media and growing accustomed to foreign ideas like platonic friends of the opposite sex, says Abdullah. Others in his generation say, even though the country’s youth may be growing more open and educated, they don’t plan to abandon traditions.

‘Controlled by traditions’

“The older generation is controlled by traditions,” Abdullah says, the family section now locked for the evening prayer. At prayer times, restaurants shutter their men-only sections, while men go out to pray. But women stay inside, so we can finish our mocha coffees unnoticed. “We need the freedom,” Abdullah explains.

But some among the older generation fear that “freedom” for 20-somethings means vice like drugs, alcohol or premarital sex. All of which, they say, are advocated by foreigners on social media.

“The problem that faces our youth is what we see as an intellectual and social invasion,” says Sheik Turkey Sultan, titled so for his advanced years and good social standing, not his religious training.

As he lounges in a chair at a traditional men’s clothing shop drinking tea with a Yemeni friend, he concludes that Saudi youth can be exposed to drugs, prostitution and terrorism without even leaving their living rooms, by outsiders online.

The Internet “affects vulnerable youth," he says, who under the influence of online outsiders could "be used for political purposes and personal gain.”

Ending separation of sexes

"Freedom" has a different meaning for Abdullah and his 26-year-old friend Abdulrahman. It means ending the enforced separation of men and women in schools, offices and many public places. This limits women’s access to education, jobs, gyms and parks, Abdulrahman says, who considers segregation of the sexes “a waste of money” and “racism.”

Abdulrahman, wearing a tee shirt and a bulky skull-cap, says that women, who make up half of Saudi society, are missing out on what little entertainment there is in Riyadh, hidden largely behind veils and closed doors.

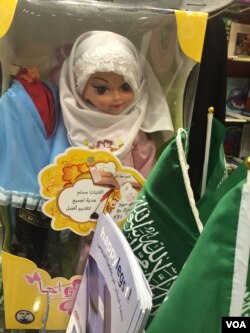

There is a dress code in Riyadh for women: loose robe-dresses called abayas have to be worn in public at all times, but the law does not require veils over faces or scarves covering heads. Yet more often than not women cover up almost completely.

Women are banned from driving in Saudi Arabia. That baffles Abdulrahman and many other young men and women in Riyadh.

“The men are hardly able to have lives here,” Abdulrahman says. “What about the girls?”

At a less covert meeting a few blocks away, in a cozy coffee shop with tinted windows patronized exclusively by women and girls, 23-year-old Asmaa Mohammad, a primary school teacher in a black veil with delicately charcoaled eyelids, says she prefers many old social habits to new ones.

She hopes colleges will one day open more departments to women, but she does not believe men and women should mix in classrooms. Mixed-gender classes are growing more popular, but Asmaa disapproves.

“Even some families now accept that a couple are friends before their marriage,” she explains. “My own mother wants me to go out with my fiance and get to know him before we marry. No, I don’t think that way.”

Secret online romance

Asmaa’s sister, 21-year-old Anjad Mohammad, joins us at the wooden booth while Asmaa slips away to talk on her mobile phone. “She sticks to the traditions,” the younger woman says of her sister, “I like the new ways.”

Even five years ago, it would be strange for two young women to wander around town like they are tonight, she says, stopping in here for a cappuccino and free wifi.

But for Anjad, the good "new ways" do not include what the men down the street say is a new courting ritual among their friends. Abdullah explained earlier that young Saudi men and women avoid arranged marriages with strangers by meeting prospective spouses online, getting to know each other on Facebook and then maneuvering to have their parents “arrange” their marriage, while the couple pretend they have never met.

“Nowadays, girls want to marry someone they know,” Abdullah says. “And if I want to get married by tradition, I can’t first see her face” - unless he and his unofficial, online woman friend meet up before the marriage is officially arranged.

Anjad agrees that female students should be admitted to more schools and that women should be allowed to drive cars, but she says there are various ways to find a suitable mate while also avoiding the taboo of meeting up with strange men. A year ago, she married her childhood sweetheart, a cousin she grew up with.

After once seeing Western-style dating in Dubai, Anjad says, she believes it would expose her generally pious nation to an immeasurable amount of sin.

“I hope we never transform to be like this,” she giggles. “I don’t even want to imagine what would happen.”

Trust is freedom, for some

Later that night, at one of Riyadh’s fanciest shopping malls, droves of women draped in black stream in and out of upscale shops like Gucci, L’Occitane and Mac cosmetics.

A manager explains that shopping malls are the only place in Riyadh with a mixed-gender social scene dominated by women. Since he has many female employees, he’s been called in for questioning by the religious police a dozen times for holding meetings in public with his female colleagues. “Forget them,” he says, frustrated.

At a traditional Arabic cafe plopped onto a shiny white linoleum floor and surrounded by stories of gleaming shops, we meet three girls eating dates with sesame seed sauce, creamy cakes and frozen coffee drinks in plastic cups.

The girls, 15-year-old Bassama, 17-year-old Selma, and their sister, 27-year Amani and her daughter, say the changes in their society, coupled by the maintenance of traditions, keeps them safe - at least from strict parents.

Their parents allow them to go out as many nights as they want, says Selma, as long as they are veiled and refrain from contact with boys.

“Where there is trust,” she explains, “there is freedom.”