This is Part Five of a five-part series on creative African artists

Continue to Parts: 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5

Suddenly the heavens cleared over the heads of five friends in the Rwandan capital of Kigali. Gunmetal gray was replaced by turquoise blue.

“It was a sky like any sky, but it wasn’t,” said Emily Mendelsohn, an American director and writer who at the time was on a Fulbright Fellowship in Uganda, collaborating with East African artists.

For Rwandan actress and poet Natacha Muziramakenga the sky represented “endless possibility.” For American performance artist and poet Elizabeth Spackman the sky made her long for her homeland on the other side of the world.

From that situation, in which each of the five women had different concepts of what that sky over Kigali meant, the seeds for a remarkable piece of theater were sown. It’s called Sky Like Sky.

The creators are Mendelsohn and Spackman, with Muziramakenga and her fellow Rwandans – actress and comedian Martine Umulisa and singer, actress and film producer Solange Umuhire.

“We started forming the play when we talked about what makes us ashamed of our countries, what shame we carry with us and how people judge us because of certain actions by our countries,” Muziramakenga explained, adding, “When you meet people anywhere in the world, they only know one thing about Rwanda – and that thing is the country’s greatest shame.”

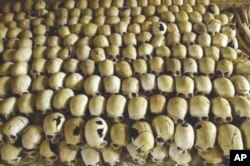

She is, of course, referring to the 1994 genocide, during which extremist militias from the Hutu ethnic group killed about 800,000 people – mostly Tutsis.

Just as Rwandans are burdened by the genocide, so people judge Americans through the prism of various controversial conflicts the United States has been involved in, including in Iraq, said Spackman.

“In our conversations we came to realize that no single people has a monopoly on perpetrating violence,” said Umuhire.

Mendelsohn said a thread running through Sky Like Sky is that the “human capacity for brutality is shared” and is not unique to countries like Rwanda.

Crossing borders

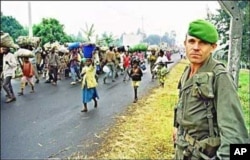

One of the brutal characters in the play is a government official who verbally and physically abuses refugees who are trying to secure documentation to cross a border. “State officials everywhere in the world often abuse their power, and that character could be seen to represent all of them,” said Mendelsohn.

Muziramakenga added, “First and foremost, the experience of crossing borders can be a bit traumatizing sometimes.”

The show is very much concerned with boundaries and borders.

“Because of various reasons, including poverty and conflict, millions of Africans are always crossing borders trying to find better lives,” said Umuhire. She added that their desperation makes them vulnerable to all kinds of mistreatment, especially by police and immigration officers.

“One of the other things that came up again and again (in the play) is (the notion) of power and how…people exercise power,” said Mendelsohn. “Because another way officials demonstrate power is by making people wait unnecessarily, simply because it’s in their power to do this and it makes them feel big.”

Sky Like Sky opens with a group of characters who are obviously extremely bored. Some gaze blankly before them; others twiddle their fingers; others sigh loudly.

Spackman explained, “In that opening scene we’re just all waiting and we don’t even know what we’re waiting for, because so much of the experience of crossing national borders is one of boredom and paperwork and filling out things that are absurd.”

Prostitute vs Policewoman

Muziramakenga emphasized that the show also explores the pain involved in transcending mental borders, “the borders of the mind.”

One scene involves intense interaction between a gruff policewoman and a provocatively dressed sex worker. The policewoman is initially disgusted by the sex worker and considers people involved in prostitution to be sub-human.

The sex worker, in turn, is initially repulsed by the police official’s viciousness. She too fails to see the officer as a human being.

But eventually their prejudices unravel and they realize that they both face many of the same problems, including a desire to be accepted by others as human beings.

“At the end they find that they have things in common. They even get to understand each other (and) they become friends,” said Umuhire. “We wanted also to…humanize people who end (up) in prostitution because we have, like, prejudice on them and we judge them easily, and we never really get to think about why (they ended) up in prostitution.”

Humor and genocide

Umulisa acknowledged that Sky Like Sky is a “dark and heavy” work. Yet the play is also littered with humor. A scene during which Umuhire, as the sex worker, flirts with Muzirakamenga, as the policewoman, and is repeatedly rebuffed by the horrified officer of the law, is particularly funny.

“You don’t have to be serious to talk about serious things,” Muziramakenga insisted. “You could talk about very serious things in a light way. And sometimes (that) highlights the seriousness even better.”

Spackman said Rwandan artists have taught her to “find light in the middle of utter darkness,” and she’s realized that “one of the really serious jobs of art is to create spaces for joy.”

She added, “Rwanda is a place that is hungry for that.”

Umulisa agreed, saying almost all of the theater currently being produced in Rwanda is about the genocide. “We wanted to do something different while still embracing our realities,” she said.

Sky Like Sky avoids addressing the genocide directly; instead, the atrocities and their implications “hover in the background,” said Mendelsohn, and are reflected in the prejudices certain characters demonstrate towards one another.

“The genocide reflected the weakness of the human race, not only the weakness of Rwandans,” said Umulisa, before stressing, “The weight of that weakness, it doesn’t erase or delete the value of our nation or the value of a Rwandan as a human being. For me, Rwanda remains a nation. The genocide, even though it was so powerful, has failed to destroy our nation. And Rwandans have kept their humanity.”

‘Miraculous’ development in Rwanda

Muziramakenga said Rwanda’s progress since the mid-1990’s, when the country was “virtually finished,” has been miraculous. She said, “I don’t know many countries which have experienced genocide and managed to live together and work together and not slaughter each other in revenge.”

Spackman described Rwanda as having an amazing capacity for development and community pride. “There’s a day every month when all communities clean their areas. The first time I arrived in Rwanda I had just been in Nairobi and I was in a car with a man from Burkina Faso and we were just glued to the windows and all we could say is, ‘It is so clean!’”

Muziramakenga said visitors to Rwanda are amazed at how safe the country is, given its history. “The first thing I love about my country is that I can walk at one A.M. – alone – and feel secure.”

She added that she was also proud of Rwanda’s commitment to the advancement of women on a continent that remains overwhelmingly male-dominated. “We’re empowering women, not only just saying things like businesses must have 30 percent women. In families they’re really sensitizing people to really, really empower women. And it’s happening – 56 percent of Parliament is women. We (women) really have a good place in our society and I love it,” said Muziramakenga.

Despite its heavy subject matter, Sky Like Sky ends not on a somber note, but with a song celebrating nations from all corners of the globe and honoring people’s ability to transcend evil.

Ultimately, said Umuhire, Sky Like Sky is a work filled with hope that shows that human beings are often able to stifle their “appetites for brutality.”

“It shows that all people are capable of doing good things. Even Americans and Rwandans,” she laughed.