In the pre-Internet era, spies faced more challenges than now when trying to infiltrate Western political circles in order to gather information, identify potential recruits, enlist the assistance of sympathizers and mount active operations, like meddling in a foreign country’s election.

Now they have the benefit of Facebook and LinkedIn and other social-media networking sites to expand their contacts, say former and current U.S. and British intelligence officials.

Western governments accuse Russian intelligence services of exploiting widely for propaganda purposes social media platforms, where they can plant “fake news,” deepen political discord in adversary states and mount influence campaigns in a bid to shape Western public opinion. But Russian spies — as opposed to trolls — are using networking sites also in highly sophisticated ways to work their way into Western political circles.

Maria Butina, the latest Russian female alleged spy who U.S. prosecutors believe they have unmasked, is an object lesson in how social media can assist covert influence operations — and not solely as propaganda platforms aimed at swaying or warping public opinion, says a U.S. counter-intelligence official who asked not to be identified for this article.

In the pre-internet era Russian influence-peddlers had to make do with trawling for "targets" at think tank and embassy events, political conferences and trade fairs. But now they can combine the physical and virtual. “Butina was using old tradecraft, turning up at political events, making contacts and then befriending them on Facebook or LinkedIn and vice versa. Social media platforms are useful in mapping out friendship networks and opening doors,” he adds.

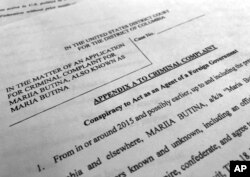

Butina, 29, was charged last week with acting as an agent for the Kremlin in the United States. The Justice Department alleges she was in regular contact with Russian intelligence services. She has been indicted for conspiracy to operate on behalf of the Russian government and failing to register as a foreign agent.

She has not been formally charged with espionage — most likely as her role was not to steal state and military secrets but to insinuate her way into U.S. political circles in ways useful for Russia’s foreign-policy aims, including deepening partisanship in Western countries and opening up avenues of influence.

Federal prosecutors accuse Butina of conspiring with two American citizens, one of whom she cohabited with, and a top Russian official to influence U.S. policy toward Russia by infiltrating the National Rifle Association gun rights group and other conservative special interest groups potentially influential on the Trump administration.

U.S. prosecutors allege in a memorandum filed in support of a request for Butina to be held in detention while she awaits trial that the Russian gun-rights activist “maintained contact information for individuals identified as employees of the Russian FSB.” Additionally, prosecutors claim FBI surveillance observed Butina having a private meal with a Russian diplomat whom the U.S. government expelled in March 2018 for suspicion of being a Russian intelligence officer.

From court papers filed by U.S. prosecutors last week it remains unclear whether her operation was initiated by Russia’s Federal Security Service, or FSB, or whether it was conceived by her patron, Alexander Torshin, a Russian central banker, as a way to boost himself within the Kremlin administration, with the FSB only getting involved subsequently.

A former British counter-intelligence officer says that’s a distinction without much meaning in a Kremlin administration seeded with so-called siloviki, Russian intelligence officers who have formally left the security agencies but are considered still active by Western intelligence officials. Many occupy high-ranking positions in the government of Russian leader Vladimir Putin, himself a former KGB officer.

Among the more traditional tradecraft techniques Butina allegedly used was offering sex to cozy up to U.S. politicians and lobbyists; in one case, according to U.S. prosecutors, to try to secure a job with an American special interest organization she had targeted. She lived with a Republican political operative twice her age. He has been identified in U.S. media as lobbyist Paul Erickson. She chafed, though, at the cohabitation, and, according to prosecutors she treated the relationship “as simply a necessary aspect of her activities.”

Butina has pled not guilty. Her lawyer, Robert Driscoll, says all she was doing was trying to help improve relations between the United States and Vladimir Putin’s Russia. And he denies she’s a spy, telling CNN Friday that much of the case against her was “taken completely out of context.”

Butina, who came to the United States in 2014 on a student visa, founded a pro-gun group in Russia called Right to Bear Arms and used gun activism in what U.S. prosecutors allege was a “calculated, patient” plan directed by Torshin to infiltrate the NRA and conservative special interest groups to make inroads into American political circles. Social media platforms were highly useful in the endeavor as she cut a swathe through U.S. conservative politics, boasting on her Facebook page of meetings with, among others, former Republican presidential candidates Rick Santorum and Scott Walker, the current Wisconsin governor.

In one e-mail to Butina, disclosed in court papers, Torshin praised her efforts, comparing them to Kremlin agent Anna Chapman, another flame-haired Russian who gained international notoriety after her 2010 arrest in the United States. Chapman and a handful of other Russians were deported to Russia in July 2010, as part of a prisoner exchange. “You have upstaged Anna Chapman,” Torshin declared.

Journalist Michael Isikoff at Yahoo News had a front seat view of Butina’s methods. He co-authored with David Corn the book “Russian Roulette: The Inside Story Of Putin's War On America And The Election Of Donald Trump” and had been tracking Butina’s activities.

He said she and Torshin had been making efforts to influence American conservative political organizations. He told the American public broadcaster NPR in an interview:

“As we reported in the book — David Corn and I — there's a Republican lobbyist who remembers being approached by her at a CPAC conference — Conservative Political Action Conference — and just being struck by how solicitous she was, how she wanted to stay in touch with him and become his Facebook friend. And this is a somewhat elderly gentleman, balding, wasn't used to this kind of attention from a young, attractive Russian woman.”

Hiding in plain sight on the internet, using overtly social media networking platforms holds risks, too. Being active on Facebook increases the chance of exposure, prompting the attention of counter-intelligence watchers, as well as journalists. In an e-mail exchange with VOA, Isikoff noted, he “friended’ her [on Facebook] in order to get in touch so I could interview her.”

And a U.S. counter-intelligence official says Butina drew attention to herself as much by her social media activity as her physical activities. So much so that she was called to testify earlier this year by the Senate Intelligence Committee, during which, according to CNN she disclosed her gun activism received funding from Russian billionaire Konstantin Nikolaev, another Kremlin-tied oligarch.

The Butina case is adding to an unfolding picture of a sophisticated and disruptive covert Russian influence campaign in the United States and the West, with the Kremlin targeting both sides of the political spectrum, say Western officials. In Soviet times, Moscow focused on far-left parties and nuclear-disarmament groups, but as a 2014 report by the Budapest-based think tank Political Capital noted, the Kremlin in recent years has become more sophisticated, courting overtly and covertly groups on the populist right of the Western political spectrum as well as the left.

The politically ambidextrous nature now of Russian intelligence and influence campaigns was dramatically captured during the 10th anniversary celebrations of the Kremlin-funded RT broadcaster in December 2015, when Green Party presidential candidate Jill Stein was an invitee to a gala dinner. She sat at the same table as President Putin — along with Gen. Mike Flynn, who served briefly as President Donald Trump’s national security adviser, before pleading guilty to lying to the FBI about contacts he had with Russian officials during Trump's presidential transition.