Russian authorities are seeking greater control of information on the internet, with some who favor tighter restrictions looking to China.

Russia's Safe Internet League, an influential lobby, hosted a first-ever forum Wednesday in Moscow with China's top internet censors, including Fang Binxing, known as the "Father of the Great Firewall of China."

Comments from speakers at the event underscored the desire for authorities to further limit and control information online.

Fang lectured on “cyber sovereignty,” arguing that countries’ borders apply to the online world as well and foreign “interference” should not be tolerated.

China’s cybersecurity and internet policy chief Lu Wei said that online freedom was not a right but a responsibility to be kept in check lest it lead to terrorism, according to a tweet from a Financial Times reporter.

Lu echoed Kremlin rhetoric, saying Western media were waging an “information war” against their countries.

Both Chinese and Russian speakers lamented American companies’ dominance of the internet. Konstantin Malofeev, who is chairman of the Safe Internet League and is linked to both the Kremlin and the Russia-backed rebels in eastern Ukraine, said Russia should learn from China’s internet censorship practices and assert its sovereignty online.

Struggle for control

Russian internet experts said the forum’s timing and high-profile guests demonstrated an urgency in the Kremlin's struggle to control information ahead of parliamentary elections later this year and presidential elections in 2018.

“I think this reflects their level of desperation inside of the Kremlin,” said Andrei Soldatov, co-author of "The Red Web: The Struggle Between Russia's Digital Dictators and the New Online Revolutionaries," who spoke to VOA via Skype. “They have these coming elections. And, it seems they need desperately to find some sort of solution to be absolutely sure that they can control the internet before the elections.”

Russian authorities increased scrutiny of online social media after they proved key to organizing mass 2011-2012 anti-Kremlin protests.

“They thought if you control the television stations, I mean, like the major TV stations, then you’re good. Then you control the public opinion,” independent TV Rain’s digital media chief Ilya Klishin said to VOA. “At that point they found out that even internet news websites and people on the Facebook and Twitter can actually organize 100,000 [-person] rallies [in] downtown Moscow.”

The movement against the Kremlin, sparked by allegations of election-rigging, petered out as arrests and intimidation fractured the opposition. A crackdown on media ensued.

Heavy fines and jail time have been introduced for anyone posting online comments deemed extremism, an incitement to hatred or an insult to revered groups such as Orthodox Christians. Prominent bloggers have been forced to register their real names.

Anton Nosik is a Moscow-based blogger and Russian internet pioneer who, just a day before the forum, was charged with extremism and inciting hatred for posts he made about bombing Syria and comparing President Bashar al-Assad’s government to Nazi Germany. He faces a fine of thousands of dollars and up to four years in prison if found guilty.

Perceived as enemy

Nosik told VOA he thought he was being prosecuted "because I'm perceived as a foreign influence, as an enemy of the state, enemy of the regime — perceived not by law enforcement as such, but rather by those guys who reported me.”

Nosik said that while China’s online censorship has long targeted politically sensitive issues that are well-known to all, such as Tibet and the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, Russia’s internet censorship goals are still developing but fast growing.

He said the Kremlin's desire to censor and control information has sparked a competition among Russian lawmakers to pass increasingly restrictive laws.

“Particular deputies are proposing laws just to make themselves noticed by their superiors and to be included in the lists for the next parliament to be elected later this year,” Nosik said. “So, many laws are proposed that curb internet freedom in very many different ways.”

Prominent bloggers and activists are targeted to send a message, Soldatov said, “because the Russian system, in large part, is based on intimidation and instigating self-censorship among journalists and among users of social networks and bloggers. That's why they use these tactics.”

While intimidation is expected to continue, fully blocking major internet sites or social networks, as China does, is not a likely option for Russia, Klishin said.

“It’s not like in China or even in Turkey, where they had YouTube or Twitter blocked. So far, they never blocked a major social network or web platform like Gmail or YouTube or Twitter," he said. "So, you know, if they would ban Facebook in Russia, then everyone would notice.”

“They found a way how to deal with journalists,” Soldatov said. “But the internet is a completely different thing, because the internet, the content, is generated by users. And [the Ukraine crisis] showed them very clearly that they cannot control social networks even if they control the company which owns social networks.”

Photos contradicted Kremlin

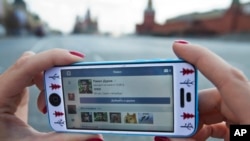

The Kremlin’s denial that it supplied troops to eastern Ukraine was discredited after Russian soldiers were found posting photos of themselves via the social network VKontakte. Its founder, Pavel Durov, sold the company in 2014 and left Russia, he said, because of pressure to turn over data to Russian authorities.

One way Russia is seeking to mimic China’s internet controls is in forcing all foreign internet service providers to base their servers with Russian data inside Russia.

“To put it very simply, the idea of the Russian surveillance is to have direct access to all the information on all servers of all internet service providers and content providers on the Russian soil," Soldatov said. “Which means that the moment, say, Google or Facebook or Twitter land their servers in Russia, all their data, including [encryption] technologies, would be immediately available ... to the Russian security services.”

While Western companies have so far resisted putting their servers in Russia, Chinese companies were praised at the forum Tuesday for having started to comply.

“The Russian security services would know what you buy in China, but of course it's absolutely incomparable with the information that we share on Facebook and Gmail,” Soldatov said. “Because, that [is] essentially private information which might be intercepted by the Russian security services and might be used against, say, activists, opposition leaders and participants of any kind of political movements.”