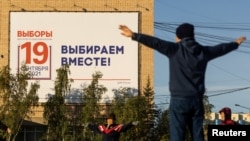

Russia’s parliamentary elections in less than two weeks' time are shaping up to be the least free since Vladimir Putin came to power 21 years ago, warn opposition leaders and independent election observers.

Polling data suggests that just 26% of Russians are ready to vote for the ruling United Russia Party in parliamentary elections on September 19 — its lowest rating since 2008.

Nonetheless few Putin opponents doubt United Russia will win the elections handsomely, thanks to ballot-rigging, the silencing of Putin critics, the barring of independent candidates, voter intimidation and cash handouts to voters.

“The thinly veiled bribery of voters, all sorts of manipulations, mobilizing administrative [resources] and persecution of the critics of the regime — these are the election tactics of Putin and his party in 2021,” according to Fyodor Krashennikov, an opposition political commentator.

Krashennikov recently left Russia for Europe, joining an exodus of opposition figures who say they’re being chased out by a crackdown on dissent, which has seen dozens of independent media outlets and civic groups forced to shut after being designated “foreign agents” or extremist organizations in a ramping up of repression up ahead of the elections.

Alexei Navalny, the most well-known Putin critic, has been in jail since January on old fraud charges, which he and some Western governments see as politically motivated. His nationwide political organization, accused by the Kremlin of being extremist, has been dismantled. Other Putin critics have been blocked from standing as candidates for the Russian Duma, including former lawmaker Dmitry Gudkov, who fled Russia in June fearing he would face criminal charges if he didn’t.

‘A hardcore autocracy’

“Since I left Russia in 2014, it is absolutely shocking how many businesspeople, academics, journalists, politicians, lawyers, NGOs leaders I used to know there who are now dead, in prison, or in exile. Simply shocking,” Michael McFaul, a former US ambassador to Russia, tweeted Tuesday.

“You never know who they are coming for next,” says Maria Snegovaya, a visiting scholar at America’s George Washington University.

She argued in a recent podcast discussion hosted by the Atlantic Council, a New York-based think tank, that 2021 will mark the year when Russia shifted into becoming “a hardcore autocracy.” She believes the mounting crackdown on dissent — which has escalated since the near-fatal poisoning last year of Alexei Navalny and protests against his jailing — is a Kremlin reaction to rising unhappiness with Putin’s government.

“Discontent runs across the political spectrum and there are way fewer supporters of the regime,” she says. Although she cautions that the anti-Putin opposition is fragmented in terms of political affiliation and shouldn’t be seen automatically as translating into support for liberal democratic ideas.

Russians will vote in elections held between September 17-19 for the State Duma -- the lower house of the Russian Parliament — as well as for several regional heads and municipal governments.

State-owned or state-controlled Russian media outlets have been dismissing claims about a rigged poll, saying it is a Western-inspired campaign to discredit Russia's elections and that fake news will soar as voting day approaches.

A group of Kremlin-friendly experts, the Independent Public Monitoring, predicted in a report Wednesday that over the next few days there will be a rise in fake news stories about public-sector workers being compelled or bribed into voting for United Russia.

“There will be extensive speculation about allegedly unequal rules of electioneering, as well as the persecution of opposition candidates,” the authors of the report told TASS, the Russian state-owned news agency.

“In their opinion, provocations and information attacks will enjoy concerted support from Western journalists, politicians and government officials. When the election campaign is over, the West will refuse to recognize the legitimacy of the new State Duma and make vigorous attempts to trigger protests inside Russia,” TASS reported.

But an opinion poll published Wednesday by the state funded VTsIOM pollster suggested 14 percent of all employees working at industrial plants in Russia have been pressured by their bosses to register to vote and more than half of respondents to the survey said their managers had raised the elections with them.

European Union officials say that the sudden wave of Russia state-owned media reports about a Western conspiracy is a preemptive exercise to try to tarnish any criticism of the Kremlin. “By inventing sinister ‘Western’ plots and provocations, the pro-Kremlin media and pundits willfully ignore and obscure the dark reality on the ground: reprisals against critics and elimination of political opposition with methods that range from cold-blooded to bizarre, censorship and restriction of media freedoms,” according to the EU’s External Action Service.

Bizarre tactics have included running spoiler candidates against the few remaining independent candidates in a bid to sow confusion. In St. Petersburg, Boris Vishnevsky, a member of the liberal opposition Yabloko party and a longtime Kremlin critic, complained Sunday that two of his opponents for a seat in the St. Petersburg Legislative Assembly have adopted his name and altered their appearance to look like him in order to reduce his votes.

“At each election for many years now we say that these were the dirtiest and most dishonest elections ever, and then at the next ones we repeat the same phrase,” Vishnevsky said.

Election observers

The absence of election monitors is also alarming opposition politicians. Last month, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, OSCE, announced it will not send observers to Russia’s elections for the first time in nearly three decades because of “major limitations" imposed by Russian authorities on the mission.

“We very much regret that our observation of the forthcoming elections in Russia will not be possible,” said Matteo Mecacci of the OSCE in an August statement. “But the ability to independently determine the number of observers necessary for us to observe effectively and credibly is essential to all international observation. The insistence of the Russian authorities on limiting the number of observers we could send without any clear pandemic-related restrictions has unfortunately made today’s step unavoidable,” he added.

Russia’s main nationwide vote monitoring group, Golos, was also labeled a month ahead of the parliamentary elections as a ‘foreign agent’ by the Kremlin and although it has vowed to continue its work there are fears it could be prohibited from conducting election monitoring.

Vote monitors fear that there will be even more opportunities to rig election results without their presence. They also note that the authorities in six major regions and in Moscow have been encouraging Russians to vote online. Electronic voting in Russia has increased in recent years but in 2020 in a plebiscite on constitutional amendment, serious anomalies emerged in the online voting in Moscow and Nizhny Novgorod Oblast with more people voting than were registered, in one precinct by 217%.

Residents of Donetsk and Luhansk, the Moscow-backed breakaway oblasts in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine, are also being allowed — and urged — by Russian authorities to vote in these elections. More than 600,000 residents of the oblasts hold Russian passports, and they are seen by the Kremlin as “additional reserves of loyal voters,” according to Russian commentator Konstantin Skorkin.

It is the first time they will be allowed to vote in Duma elections. Last year, Russian passport-holders in Donetsk and Luhansk were permitted to vote in the plebiscite amending the Russian constitution to allow Putin to run again for two more presidential terms. They were bused over the border and voted in the Russian region of Rostov, but only 14,000 did so.

This time they will be able to vote online.