For the past few years, Russia’s disinformation apparatus has seemed unstoppable.

With the adept planting of falsehoods and red herrings on social media platforms by troll factories, and then amplified by Russia’s official news outlets such as RT, the Kremlin time and again has been able to confuse issues, obfuscate facts and define false narratives, manipulating audiences which might be receptive, say Western officials and independent analysts.

They have often expressed frustration at how Russian disinformation has gained traction, managing to roil the 2016 race for the U.S. presidency, worsen political divisions in Europe during the 2015-16 refugee crisis and in Syria shaping a narrative linking opponents of Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad, as well as the first-responders the White Helmets, with jihadists and the Islamic State terror group.

But as Russia’s armed forces have been caught wrong-footed on the battlefield in Ukraine by a smaller, agile and more motivated opponent, so, too, its propaganda operation has seemed flat-footed. The storylines promulgated by the Kremlin as it seeks to shift blame for its own actions on to others, and to cast its invasion as defensive in nature, have struggled to gain the traction Russian propagandists might have expected, they say.

CIA Director Bill Burns told a U.S. congressional committee last week that in his view Russian President Vladimir Putin is “losing the information war” over Ukraine. He is not the only one who sees it that way.

“Vladimir Putin has long enjoyed a reputation as a master of information warfare. Over the past decade, his weaponization of social media and aggressive promotion of fake narratives have proven pivotal,” notes Anders Aslund, a senior fellow at the Stockholm Free World Forum, a foreign policy think tank in Sweden but Aslund assesses “it is already clear that the information war has been decisively lost” by Russia.

Aslund and other observers say that despite Russia’s turning to its sophisticated disinformation playbook the international community has rallied overwhelmingly to support Ukraine, judging Russia’s invasion in good versus evil terms, and has imposed unprecedented economic sanctions. Major global brands and companies have scrambled to cut ties with Russia, and humanitarian donations to Ukraine from institutions and individuals around the world have soared. Martin Griffiths, the U.N.’s emergency relief coordinator, noted Monday how his office alone has received aid donations from 143 countries.

So why has Russia’s well-practiced disinformation machine failed to muddy the waters as so often in the recent past when it has had success in confounding facts with fictions? Maybe the reason is simple, says Tetiana Popova, a public-relations expert and a former Ukrainian deputy Minister of Information. “The best counter propaganda is truth,” she told VOA.

Efforts thwarted

The on-ground presence of a large international press corps and the speed and alertness of Ukraine’s own formidable and experienced information warriors, who have been quick to seize on Russian statements to demonstrate their falsity, have thwarted Russian propagandists’ efforts to control the narrative of the war. Ukraine’s information warriors have often out-paced their Russian rivals, she and other observers say.

Russian disinformation has increasingly been scorned across the world and labeled Orwellian. When Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov on March 10 rejected the prodigious visual evidence and eye-witness testimony demonstrating Russian forces have been targeting Ukrainian civilians, his comments were met with widespread astonishment — as was his surprising contention Russia had not attacked Ukraine at all.

Michael Willard, a former managing director in Russia and Ukraine of the global PR company Burson-Marsteller, believes Putin and his top officials have been “clumsy” and “ham-fisted with their communications tactics.” “Modern communication has shrunk the globe. News eventually slips out,” he says.

The distortions, including from the get-go that Putin was merely launching a “special military operation” and not mounting an invasion, have been too large for Russia’s infamous disinformation machine to finesse, he and other PR and marketing experts say. Open-source investigators and freelance geo-locators, such as Bellingcat, a journalist consortium founded by British blogger Eliot Higgins, have made it even harder for Russian propagandists to shape a half-convincing narrative for audiences most likely to be receptive.

Last week, after Russian shelled a maternity hospital in the besieged port-town of Mariupol, in which three people including a child were killed immediately and 17 people injured, a coordinated effort by Russian embassies around the world, supported by Kremlin-controlled troll factories, sought to establish the story that the hospital had been turned into a military base by Ukrainian-nationalists. “The truth is that the maternity hospital has not worked since the beginning of Russia's special operation in Ukraine,” tweeted Russia’s embassy in Israel. “The doctors were dispersed by militants of the Azov nationalist battalion,” it added.

But the photograph Russian embassies posted to show where Ukrainian militiamen were based was geolocated by investigators affiliated with Bellingcat as being ten kilometers from the maternity hospital. RT, the Kremlin-controlled television channel, devoted a whole segment Monday attacking Bellingcat and NGOs such as Amnesty International for what it accused of disinformation in their documentation of the shelling of apartment buildings and humanitarian corridors for civilians to flee as well as the use in residential areas of cluster bombs, air-dropped or ground-launched explosives that release or ejects smaller submunitions.

Ordinary Ukrainians have been keen to document the war, using their cell phones to record bombardments and their destructive consequences.

Russia’s information war campaign has also faced other major setbacks with social-media giants Facebook and Twitter taking steps to remove Russian and Belarusian disinformation from their platforms and to dismantle suspicious networks seeking to manipulate algorithms to push inauthentically a pro-Russian narrative. And Russian’s disinformation campaign has been severely hampered by the European Union’s ban on Russian state-controlled media outlets RT and Sputnik broadcasting to the 27-nation bloc.

'Manipulation ecosystem'

The EU's top diplomat Josep Borrell told EU lawmakers after the ban was announced: “They are not independent media, they are assets, they are weapons, in the Kremlin's manipulation ecosystem.” He added: “We are not trying to decide what is true and what is false. We don't have ministers of the Truth. But we have to focus on foreign actors who intentionally, in a coordinated manner, try to manipulate our information environment.”

Above all, Russia’s disinformation machine has little answer on the global stage to Ukraine’s social-media savvy President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and his daily video addresses which have become viral sensations and have helped rally support for his embattled nation.

In the head-the-head match-up between the man-of-the-people TV comedian versus the stiff spymaster, Zelenskyy comes off better. “Seen from the perspective of one who studies crisis leadership, he has been extremely effective,” according to historian Nancy Koehn, author of the book Forged in Crisis, which examines wartime leadership.

“He has demonstrated a deft ability to pivot and improvise as the circumstances of the crisis shift. He is communicating brilliantly with his own people and citizens across the world, seemingly getting better as the days pass,” she told the Harvard Gazette. “Then add in the emotional awareness and moral clarity that Zelenskyy uses, again and again, to explain to the rest of the world what is happening to his nation and people. And his personal bravery and unshakable commitment to beat back Putin’s aggression, even in the face of great odds, are not only inspiring to millions of others, they are also a source of real personal power for the leader himself,” she added.

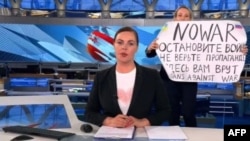

Even in the rigidly controlled media environment of Russia, the Kremlin has faced challenges. An employee of Russian state-run Channel One managed to interrupt a live broadcast of the nightly news Monday shouting “Stop the war! No to war!” News staffer Marina Ovsyannikova, whose father is Ukrainian, held up a placard in Russian, saying, “Don’t believe the propaganda. They’re lying to you here.” Studio producers rushed to cut her off.