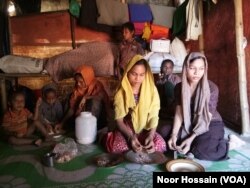

Bangladesh handed over a list of more than 8,000 Rohingya refugees to Myanmar last week to kick-start their repatriation. But Rohingya community members in Bangladesh say they are not willing to return to Myanmar because the situation for them is still hostile in Rakhine, where they lived.

“Persecution of the Rohingyas is still going on and they are still fleeing Myanmar every day. The soldiers killed my wife and son. No action has been taken against those who raped and murdered so many Rohingyas. With all perpetrators still at large there we will not feel safe in Rakhine at all,” Abdur Rahman, a Rohingya refugee in Balukhali camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, said. “We cannot return to Rakhine in this situation.”

Ko Ko Linn, a Rohingya refugee community leader in Bangladesh, said that Rohingya would not return to Myanmar because the government seems to have decided to force them into some new settlements away from the villages where they lived.

“Almost all of the around 300 villages of Rakhine, from where the Rohingyas were driven away, have been set on fire in the past months. At least 48 of those villages were completely flattened using bulldozers in the past weeks. It’s clear they do not want the Rohingyas to return to the villages where they lived,” he told VOA. “None from our community wants to enter Myanmar’s new settlements, which are nothing but open air prisons.”

Following a military crackdown in August, in which Myanmar’s soldiers were accused of rape, murder and arson in Rohingya villages, hundreds of thousands of ethnic Rohingya began crossing over to neighboring Bangladesh. Myanmar has strongly and consistently denied the allegations of abuses and atrocities.

Late last year, Bangladesh signed a deal with Myanmar to repatriate some 700,000 Rohingya refugees. Last month, Bangladesh Home Minister Asaduzzaman Khan Kamal handed over a list of 8,032 Rohingya refugees to his Myanmar counterpart, Lieutenant General Kyaw Swe, following a meeting in Dhaka.

Myanmar Social Welfare, Relief & Resettlement Minister Win Myat Aye told VOA’s Burmese Service in a recent interview that Myanmar’s immigration ministry was trying to verify the list received from Bangladeshi authorities.

“It’s now under verification in accordance with the agreement. This verification process already took actions for two days now. I think it will take about a week to finish the verification work and will send it to the Bangladesh authorities,” the Myanmar minister said. “We can accept 300 refugees per day through two border crossing points.”

An unsafe return

But Rohingya refugee community leaders accuse the Myanmar government of being insincere about the issue of repatriation.

Linn said with the Rohingyas still being targeted violently in Rakhine, the conditions are not good for them to return to Myanmar.

“Last week the authorities in Burma said they were verifying the list of the Rohingyas for repatriation. But, even this week we saw the Rakhine militants loot many Rohingya households and the security forces set alight their houses. On March 1, Burmese forces violently threatened around 6,000 displaced Rohingyas living in no man’s land and fired at them, forcing half of them to cross over to Bangladesh,” he said.

Since the talks between Bangladesh and Myanmar, Rohingya at the main refugee camp in Cox's Bazar have held several demonstrations to protest the repatriation process. Many said that while they would be happy to return to their homeland in Myanmar, but only if the country agrees to “return” them their citizenship and guarantees their safety.

“They must keep U.N. peacekeeping forces ready in Arakan for our security before we return. Burma (Myanmar) must accept us as ethnic Rohingya and return our citizenship and related basic rights. They must allow us to return to our villages where we lived and return our confiscated lands and compensate for our losses because of the military crackdown,” said Mohammad Islam, a Rohingya community leader in Cox’s Bazar.

Most Rohingya do not possess citizenship in Myanmar, where the government says they must accept the label Bengali, a term rejected by most Rohingya leaders.

The whole bi-lateral repatriation scheme has been fundamentally flawed right from the start because both Myanmar and Bangladesh did not involve the Rohingya in the negotiations, said Phil Robertson, deputy director of the Asia division of Human Rights Watch.

“No wonder the Rohingya are wholly unsatisfied with Burma’s promises for ‘security’ if they return because there are no real guarantees for protection, no international monitors, no accountability for past rights abuses, and no way to prevent a Burmese soldier from turning on them again,” he said.

He added that the refugees should not be returned to camps guarded by the very same forces who forced them to flee massacres and gang rapes.