Syrian rebel commanders acknowledge they are in an existential, make-or-break moment of the uprising against President Bashar al-Assad. The five-year civil war has seen plenty of tortuous battlefield ups and downs.

Between May and August last year, the Assad government looked almost defeated after suffering some stunning military reversals, losing Idlib to an alliance consisting mainly of al-Qaida affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra and the hardline Islamists of Ahrar al-Sham, and then Palmyra to the Islamic State.

Rebel commanders talked of marching to the coast and grabbing Latakia or heading south to Homs, where they thought they might be confronting an advancing IS before storming into the Syrian capital, Damascus.

In August, a growing number of soldiers and civilians in government-controlled areas of Syria were expressing rare public disaffection with the Assad regime. In traditionally loyal coastal regions, noncombatants as well as the military were complaining that not enough was being done to relieve enclaves besieged by rebels.

Now the battlefield map has been turned upside down — and no thanks to the Syrian army, which has not been doing most of the heavy lifting.

“Eighty percent of the regime’s ground forces in offensive are not Syrian — they are Iranian, Lebanese, Iraqi and Afghan Shi’ites,” says Gen. Salem Idris, former chief of staff of the Western-backed Free Syrian Army.

Outside Influence

And the strategic brains behind the offensive that has swept the northern Aleppo countryside, tightening the noose around rebels in the districts they hold in the city of Aleppo, have not been Syrian either.

Most Syria watchers and Western military analysts believe the offensive was planned in July 2015 by Iranian military commanders led by Major General Qasem Soleimani, head of the Quds Force, the special forces of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards, and Russian generals experienced in the counter-insurgency operations in Chechnya.

The overall strategy — to crush the more moderate armed factions in the opposition, leaving the extremists — is straight out of the Chechnya playbook, say military analysts.

So too are the scorched-earth indiscriminate tactics of the airstrikes that are meant to sow panic and force civilians to flee. According to local eyewitnesses, civilians have stampeded out of villages and towns in the northern Aleppo countryside such as Tell Rifaat and Mare’, once the headquarters of the FSA in northern Syria.

The build-up for this month’s blistering offensive was done patiently, says a European diplomat.

“First the Russians slipped a few warplanes into the Khmeimim airbase in Latakia to see if they would get a Western reaction. And when they didn’t, they dispatched more, and we still reacted in just a muted way as evidence mounted of ground forces, tanks and mechanized units being sent in,” he says.

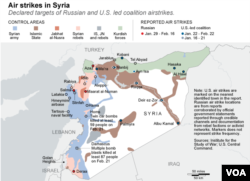

“Then they focused on pressing offensives around Latakia, ensuring the safety of their bases and creating a buffer zone running north to south, sealing off the northern Hama border with Idlib,” he says.

The Syrian government-Russian offensive was then extended to the al-Ghab plains between northwest Hama and southwest Idlib. The objective was to cut off Idlib and by extension the province of Aleppo from the center, west and southwest of the country.

As the government pressed offensives in Hama and Idlib, it also launched a large-scale campaign in the northern Latakia countryside, seizing 200 square kilometers of rebel-held territory bordering Turkey.

“By then,” says the diplomat, “they had the bulk of rebel forces boxed in the provinces of Idlib and Aleppo with no chance of them forcing their way to Homs or trying to link up with rebels around Damascus or insurgents trying to come up from the south of the country.”

And then, in late October and November, the government launched a large-scale offensive in the southern Aleppo countryside, with the main objective of the operation being to secure the Azzan Mountains and to establish a buffer zone around the Syrian government’s only highway leading to the parts of Aleppo city it controls.

The rebels made a strong stand, destroying dozens of tanks. But they were unable to deny government forces - including the 4th Mechanized Division - Hezbollah and Iraqi Shi’ite militias, as well as Afghan volunteers and Iranian Revolutionary Guardsmen, from accomplishing their objectives.

Aleppo Offensive

The even stronger offensive this month in northern Aleppo has three objectives: to sever supply lines from Turkey to rebels in the city of Aleppo and to prepare a siege; to expel anti-Assad insurgents from their long-standing stronghold in the north of the countryside; and to take back control of the border around Bab al-Samah.

Western intelligence and military officials tell VOA that with the help of Kurdish fighters from the People’s Protection Units (YPG), those goals have now nearly been reached.

“I think Moscow will halt most airstrikes in the northern Aleppo countryside by March 1 — they won’t need to maintain them with the intensity they have the past week,” says a British military official.

“And if they need to pop off a few missiles they will claim they are hitting ‘terrorists’ therefore abiding by the Munich cessation of hostilities agreement,” he added.

That agreement will allow them to turn their focus on Idlib, the stronghold of Jabhat al-Nusra and Ahrar al-Sham, he says.

Gen. Idris agrees, the focus will now swing to Idlib.

“They want to close down Bab al-Hawa,” he said, referring to the border crossing west of Bab al-Samah.