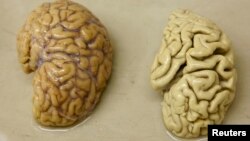

Scientists have found a mechanism that kicks in when the body is cooled and prevents the loss of brain cells, and say their find could one day lead to treatments for brain-wasting diseases such as Alzheimer's.

Studying mice, the researchers were able to simulate the effects of body cooling and pick apart the workings of a so-called “cold-shock” protein in the brain, RBM3, which has previously been linked with preventing brain cell death.

“We've known for some time that cooling can slow down or even prevent damage to brain cells, but reducing body temperature is rarely feasible in practice [because] it's unpleasant and involves risks such as pneumonia and blood clots,” said Giovanna Mallucci, who led the research.

By identifying how cooling activates a process that prevents the loss of brain cells, we can now work towards finding a means to develop drugs that might mimic the protective effects of cold on the brain.”

Scientists already know that lowering body temperature can protect the brain. People can survive hours after a cardiac arrest with no brain damage after falling into icy water, for example, and artificially cooling brains of babies with oxygen deprivation at birth can also protect against brain damage.

'Cold-shock'

Cooling - and hibernation in animals - prompts production of certain brain proteins known as “cold-shock” proteins. One of these, RBM3, has been linked with preventing the death of brain cells and synapses, but scientists are not sure how it works.

Knowing how these proteins affect synapse regeneration might help researchers find a way of mimicking them without needing to cool the body down.

Mallucci's team reduced healthy mice’s body temperatures to 16-18 degrees Celsius - similar to that of a hibernating small mammal - for 45 minutes and found that the mice's synapses dismantled on cooling and regenerated when re-warmed.

The team then repeated the cooling in mice that had been specially bred with features of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's and found the capacity for synapse regeneration fell as the disease progressed, and that RMB3 levels also dropped.

When the scientists artificially boosted levels of RBM3 they found it protected the Alzheimer's mice, preventing synapse and brain cell depletion.

Hugh Perry, chairman of Britain's Medical Research Council's neurosciences and mental health board, which funded the research, said the finding may be an important step forward.

“We now need to find something to reproduce the effect of brain cooling. We need to find drugs which can induce the effects of hibernation and hypothermia,” he said.