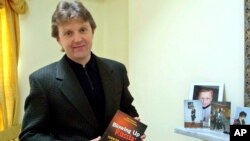

Britain on Tuesday overturned its decision not to hold a public inquiry into the death of former KGB spy Alexander Litvinenko, who accused Russian President Vladimir Putin of ordering his murder from his London deathbed in 2006.

A year ago, the British government rejected a request for an inquiry into the killing of Litvinenko, who died after drinking tea poisoned with a rare radioactive isotope in a plush London hotel, leading to accusations it wanted to appease the Kremlin which has always denied any involvement in the death.

The reversal of that decision comes as Prime Minister David Cameron leads calls for hard-hitting sanctions against Russia, including freezing the assets of Putin's close allies, after the downing of Malaysian airliner MH17 in Ukraine last week.

Cameron's office would not comment on the timing of the announcement but sources told the BBC it was a coincidence, coming on the day before parliament rose for its summer break.

An inquiry may well strain Anglo-Russian relations further, having mirrored diplomatic ties between the two for years.

“It is more than seven years since Litvinenko's death, and I very much hope that this inquiry will be of some comfort to his widow,” Britain's interior minister Theresa May.

The inquiry would be chaired by judge Robert Owen, who was the coroner in charge of an inquest into Litvinenko's death, and who has said there was evidence indicating Russian involvement in the murder, Home Secretary May said in a statement.

Owen himself had called for an inquiry saying an inquest - a British legal process held in cases of violent or unnatural deaths - could not get to the truth because he could not consider secret evidence held by the British government.

Post-cold war low

Relations between the countries fell to a post-Cold War low following the death of the 43-year-old Kremlin critic who had been granted British citizenship. He died days after being poisoned with polonium-210.

British police and prosecutors have said there was enough evidence to charge former KGB agents Andrei Lugovoy and Dmitry Kovtun with murder, but Moscow refused to extradite them, and Lugovoy, who denied involvement, was later elected a lawmaker.

After Cameron took power in 2010, he made a concerted effort to improve relations, with an eye on strengthening trade links.

When May rejected calls for an inquiry last year, she admitted she had taken into account the interests of Anglo-Russian relations, but said it had not been the main factor.

However, it led to accusations from Litvinenko's family that the government was covering up what their lawyers described as “state-sponsored nuclear terrorism” to protect the Kremlin.

Litvinenko's widow Marina launched a legal challenge and, in February, London's High Court quashed May's decision and told her to reconsider the issue.

In his formal submission to the High Court as coroner, Owen wrote that the secret evidence did “establish a prima facie case as to the culpability of the Russian state in the death of Alexander Litvinenko”.

Hearings ahead of the inquest also heard that Litvinenko had been working for Britain's Secret Intelligence Service, known as MI6, for a number of years.

Marina Litvinenko said she was “relieved and delighted”.

“It sends a message to Sasha's (her husband's) murderers: no matter how strong and powerful you are, truth will win out in the end and you will be held accountable for your crimes,” she said in a statement.