BEIJING —

China has launched an intense media campaign to defend the safety of producing a chemical used to make polyester fiber, as public opposition to new petrochemical plants threatens to disrupt expansion plans by state energy giants.

Choking smog and environmental degradation in many parts of China is angering an increasingly educated and affluent urban class, and after a series of health scares and accidents there is deepening public skepticism of the safety of industries ranging from food to energy.

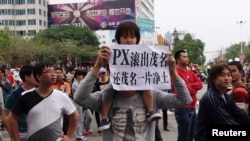

Illustrating this distrust, hundreds of residents in the southern Chinese city of Maoming demonstrated this month against plans to build a petrochemical plant to produce paraxylene, known as PX, a chemical used in making polyester fiber and plastics.

The plant is backed by the local government and China's biggest refiner, state-controlled Sinopec.

China is the world's largest producer and consumer of PX and polyester, vital for the country's textile industry, which generated $290 billion of overseas sales, or 13 percent of China's total exports last year, according to customs data.

State television, CCTV, last week aired six short features showing staff reporters visiting petrochemical facilities in Japan, South Korea and Singapore producing PX in a bid to assure the public over safety.

China's state-dominated oil and petrochemical sector has had a poor safety record in the last decade.

Accidents have included a gas well explosion in the sprawling municipality of Chongqing in 2003 that killed 234, a 2005 chemical leak into a river in Jilin that poisoned drinking water and a pipeline explosion in Qingdao that killed 62 last November.

“The reason why the industry has lost credibility is not that it hasn't carried out public relations or education work properly, but because of repeated accidents,” said Ma Jun, head of the Institute of Public & Environmental Affairs, an independent environmental group.

China still relies heavily on importing PX. Last year, China imported just over 9 million tons worth about $18 billion, mainly from South Korea, Singapore and Japan, exceeding domestic output of 8.3 million tons.

There have been demonstrations in six Chinese cities since 2007 against plans for PX plants, forcing at least one plant to relocate and another two to be shelved or canceled.

The state media campaign on television and online has sought to reassure the public over the safety of PX.

One CCTV broadcast showed a middle-aged man taking a stroll at a beachside park in Singapore, across from the city state's chemical hub of Jurong Island, saying he liked walking in the park because “the air there was fresh.”

A CCTV story headlined “Telling you the truth on PX” said that countries such as the United States did not treat PX as a toxic chemical.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency says effects from exposure to the xylene group of chemicals derived from refining oil - including mixed xylene and paraxylene - can range from nose and throat irritation to memory impairment, though they are not classified as cancer-inducing.

Cao Xianghong, a former senior vice president at Sinopec, told a government-backed conference of nearly 300 participants on PX that the petrochemical industry had to share some of the blame for the public concerns, particularly in the way safety and environmental issues have been managed.

“The serious pollution cases and accidents that the industry has had have naturally scared people,” Cao said at the PX forum last week organized by the China Association for Science and Technology.

Choking smog and environmental degradation in many parts of China is angering an increasingly educated and affluent urban class, and after a series of health scares and accidents there is deepening public skepticism of the safety of industries ranging from food to energy.

Illustrating this distrust, hundreds of residents in the southern Chinese city of Maoming demonstrated this month against plans to build a petrochemical plant to produce paraxylene, known as PX, a chemical used in making polyester fiber and plastics.

The plant is backed by the local government and China's biggest refiner, state-controlled Sinopec.

China is the world's largest producer and consumer of PX and polyester, vital for the country's textile industry, which generated $290 billion of overseas sales, or 13 percent of China's total exports last year, according to customs data.

State television, CCTV, last week aired six short features showing staff reporters visiting petrochemical facilities in Japan, South Korea and Singapore producing PX in a bid to assure the public over safety.

China's state-dominated oil and petrochemical sector has had a poor safety record in the last decade.

Accidents have included a gas well explosion in the sprawling municipality of Chongqing in 2003 that killed 234, a 2005 chemical leak into a river in Jilin that poisoned drinking water and a pipeline explosion in Qingdao that killed 62 last November.

“The reason why the industry has lost credibility is not that it hasn't carried out public relations or education work properly, but because of repeated accidents,” said Ma Jun, head of the Institute of Public & Environmental Affairs, an independent environmental group.

China still relies heavily on importing PX. Last year, China imported just over 9 million tons worth about $18 billion, mainly from South Korea, Singapore and Japan, exceeding domestic output of 8.3 million tons.

There have been demonstrations in six Chinese cities since 2007 against plans for PX plants, forcing at least one plant to relocate and another two to be shelved or canceled.

The state media campaign on television and online has sought to reassure the public over the safety of PX.

One CCTV broadcast showed a middle-aged man taking a stroll at a beachside park in Singapore, across from the city state's chemical hub of Jurong Island, saying he liked walking in the park because “the air there was fresh.”

A CCTV story headlined “Telling you the truth on PX” said that countries such as the United States did not treat PX as a toxic chemical.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency says effects from exposure to the xylene group of chemicals derived from refining oil - including mixed xylene and paraxylene - can range from nose and throat irritation to memory impairment, though they are not classified as cancer-inducing.

Cao Xianghong, a former senior vice president at Sinopec, told a government-backed conference of nearly 300 participants on PX that the petrochemical industry had to share some of the blame for the public concerns, particularly in the way safety and environmental issues have been managed.

“The serious pollution cases and accidents that the industry has had have naturally scared people,” Cao said at the PX forum last week organized by the China Association for Science and Technology.