There has been much worldwide admiration for the way in which the Japanese people affected by last month's earthquake and tsunami have coped with the hardship. Despite the hundreds of thousands of people made homeless and the shortages of basic supplies, the unwritten rules that govern life in Japan appear to be holding the society together. And it's not only those directly affected by the disaster who are changing their lifestyles.

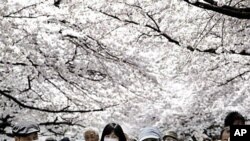

It is cherry blossom season in Japan - traditionally a time of celebration and renewal. But this year the mood is subdued.

Ueno Park in Tokyo would normally be covered with families and friends picnicking under the trees. But the parties are now few and far between. Last month’s devastating tsunami has pushed Japan into a period of ‘jishuku’ - or collective self-restraint.

Tatsuo Tatsuno and his wife Yoko, both in their seventies, are among those out for a stroll in the park. Yoko says we should not be enjoying ourselves while all this is happening. She says those people in the north [affected by the tsunami] really need to fight hard to recover.

Tatsuno agrees. "We are old," he says. "We are just about surviving too. We should all fight to get through this."

Images of the devastation in the north are broadcast continuously on Japanese television. The sense of shared experience has permeated throughout Japanese society, says Kyle Cleveland, an Associate Professor of Sociology at Temple University.

"Most of the devastation has happened not in the big cities but in places that are essentially villages. And the impact has fallen disproportionately on older people. And so the response here also reflects an older generation who have experience of what happened during the [Second World] War, and their way of responding to this is I think leading the societal response," said Cleveland.

Shortages of fuel, water and food have affected much of northern Japan.

Hiroko Nagauna is raising a 10-month-old baby. She says her biggest concern is what happens to the damaged Fukushima nuclear plant. She says what concerns her most is that the nuclear danger is mostly unseen. It does not show any immediate effects, the symptoms take time.

Many outside observers have remarked on the stoicism the Japanese people have shown in the face of disaster. An estimated 200,000 people made homeless by the tsunami are still living in temporary shelters.

But the clean up is well underway thanks to a huge government and international relief effort - and an army of volunteers who have arrived in the quake region from across Japan. Sociologist Kyle Cleveland says the Japanese response reflects their values.

"I think what’s happening here though is that the Japanese are just expressing some Japanese values and ways of behaving that are not that atypical of the society but are perhaps highlighted by the events of recent days. This is likely to have long-term consequences on Japanese society. And I think it’s leading to a reconsideration of Japanese values, concern for others, and I think that’s what this ‘jishuku’ represents in the short term," said Cleveland.

This man selling roasted sweet potatoes - a traditional Japanese street food - in Tokyo’s Ginza shopping district is doing a good trade. It is a sign perhaps of the austerity that has gripped this city.

The sudden period of economic self-restraint has quieted once popular sushi bars and karaoke clubs. Their owners fear it could put them out of business. Tokyo’s sidewalk fortune-tellers are among the few traders still open.

Japan’s fortunes could well depend on how long it takes people to emerge from this period of quiet self-reflection.

Response to Disaster Reinforces Japanese Tradition of Self-Restraint