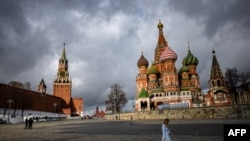

Russia has spent at least $300 million to sway both politics and policy in more than two dozen countries since 2014, according to a newly declassified review by U.S. intelligence agencies that warns the Kremlin is not done with plans to pay for influence.

The money, funneled to political parties and candidates across at least four continents through various front companies, is likely "just the tip of the iceberg" with the U.S. and its allies scrambling to track down additional, illicit contributions.

"These are minimum figures," said a senior U.S. administration official who spoke to reporters Tuesday on the condition of anonymity in order to discuss the intelligence.

VOA has emailed the Russian Embassy in Washington seeking comment.

"Russia likely has transferred additional funds covertly in cases that have gone undetected," the official added, cautioning that the war in Ukraine could well spur Moscow to increase its efforts to finance political parties and candidates to "undermine international sanctions and maintain its influence around the world."

The U.S. intelligence review, completed over the past several months, concluded Russian efforts increased dramatically starting in 2014, spreading from Europe to Africa and the Americas.

A U.S. official familiar with the intelligence but not authorized to speak on the record said countries swept up in the Russian covert funding efforts include Albania, Bosnia, Montenegro, Belgium and Madagascar.

In at least one case, Russia used cutouts, or intermediaries, to transfer money to far-right nationalist parties.

As a first step, the U.S. officials said, the State Department has issued a cable to 110 countries sharing the findings and will review steps countries can take to counter Russia's efforts.

Additionally, U.S. intelligence officials are privately briefing select countries whose elections and political processes have been specifically targeted by the Russian campaign.

The U.S. intelligence review did not specifically look at Russian activity in the United States, but with the country's midterm elections set to take place in less than two months, officials cautioned that not even Washington is immune.

"There's no question that we have this vulnerability as well, and that Russian covert political influence poses a major challenge," the first official said.

While the warning — and the data — from U.S. officials about Russia's attempt to meddle with the internal politics of other countries is new, the concerns are not.

Some U.S. officials began saying as far back as late 2014 that Russia, under President Vladimir Putin, was playing a dangerous game by engaging with and encouraging nationalist groups across Europe.

By 2018, Estonia's Foreign Intelligence Service and other Western intelligence agencies were also sounding the alarm.

"We have detected a network of politicians, journalists, diplomats, businesspeople who are actually Russian influence agents and who are doing what they are told to do," Mikk Marran, Estonia's spy chief, told an audience at Aspen Security Forum at the time.

Specifically, Estonia's intelligence agency warned that the Kremlin was perfecting its playbook across Europe, seeking out fringe political groups, both on the far-right and the far-left, and offering money, advice or business opportunities designed to help the groups and their candidates get a foothold.

"Politicians that have been in the margins of local politics some years ago are actually right now in national parliaments or national governments," Marran said at the time. "They have made some bad investments, but they have also made some very good investments."

Researchers say that Russia has expanded its outreach from Eastern Europe and the Baltics into Western Europe, Africa and beyond.

At the same time, Russia's options for funneling money and other aid to political groups and candidates also grew to include Russian expatriates and oligarchs, shell companies, foundations, think tanks, adoption agencies and charities.

"They're opportunistic," Josh Rudolph, a senior fellow for malign finance at the Alliance for Securing Democracy, an election security advocacy group, told VOA, arguing that covert political funding appears to be one of three legs — along with cyberattacks and social media influence campaigns — of Russia's election meddling strategy.

"They seem to do it when they think they have a shot, when it's a close election," he said.

And whether an individual effort on behalf of a particular party or candidate succeeds or fails may not matter.

"It is essentially impossible to measure precisely the impact," Rudolph said, echoing the sentiment of some U.S. officials. "The point is that they are trying and putting significant resources into it in closely contested elections."

That effort includes targeting the U.S.

A 2020 bipartisan report by the U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee concluded Moscow used a complex web of operatives and active measures to ensnare members of former President Donald Trump's campaign, in some cases, leaving the incoming administration open to manipulation.

A report issued that same month by Rudolph and the Alliance for Securing Democracy concluded that, even then, the U.S. had become the most frequent target.

That report also found Russia was not alone, and that China and a handful of other countries had also begun copying the Russian tactics.

"You certainly see them in Taiwan and Hong Kong but then also in the developed democracies of Australia and New Zealand," Rudolph told VOA. "Increasingly, they've kind of dabbled with going further afield, whether it's the Czech Republic or Chad or Kenya, or in some limited cases, funding ads or media operations that influence the United States."

VOA has emailed the Chinese Embassy in Washington seeking comment.

And while the recipients of the covert funding may plead ignorance, researchers and U.S. officials believe most have at least some level of awareness.

"It is clear that the parties in question are interested in having that funding," the senior U.S. administration official said of those benefiting from Russian money. "Clearly, those parties believe their effectiveness will be enhanced the more funds they have."

Nike Ching contributed to this report.