At early light they come, the Russian warplanes – mostly just silver flashes in the sky, sometimes roaringly close – unleashing "dumb" munitions and guided missiles depending on the target, scorching the countryside south of Aleppo.

They are followed by mechanized units of the Syrian army backed by Iranian-trained Shi'ite fighters mainly from Iraq, but some Afghans, too, who will be rewarded with Iranian passports when their enlistment finishes, if they survive.

In the flat countryside the regime has the edge during the day; but at night or whenever the jets are absent insurgents reclaim territory they retreated from hours earlier, staking out temporary defensive positions, prompting new rounds of aerial bombing heralded by the dawn.

“The ground offensive is the biggest we have seen in the Aleppo countryside in two years,” says Abdul Rahman, a commander with the Ahfad Omer battalion, part of the larger First Brigade, a U.S.-backed secular militia.

Similar to Grozny

“The Russians are burning and flattening everything,” Rahman explains, arguing the scorched-earth tactics are reminiscent of what the Russians did to the Chechen capital Grozny in 1994, reducing it to rubble.

“There are 50 or 60 airstrikes a day,” he said. The difference is the Russians are not bombing a built-up city, but spread-out villages, some the poorest in northern Syria.

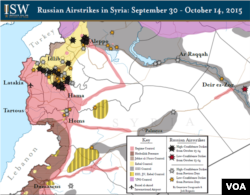

In more than a dozen interviews, war-weary but defiant rebel commanders acknowledged to VOA the Russian intervention has changed the dynamics on the battlefields across northern Syria, from coastal Latakia through the inland provinces of Hama and Idlib, and then into Aleppo governorate.

'They are bombing us'

They dismiss recent claims by Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov that Russia is ready to help units of the "patriotic opposition" in Syria, specifically the Free Syrian Army, if only they knew their whereabouts.

“They know where we are, they are bombing us,” said Abdul Rahman.

“It has been clear Russia has been attacking anti-Assad rebels. If they are serious, we don’t need the help of the Russians and they should leave now,” said Major Issam al-Reis, an FSA spokesman.

The rebels battling to topple President Bashar al-Assad insist there’s no risk of their insurgency collapsing. They respond with derision at suggestions of a political solution.

“The solution is simple. It is not complicated. Assad, his inner circle, the security apparatus and all the intelligence agencies, all have to go,” said 35-year-old Zakaria Malahefji, a former higher education teacher and political officer of the 3,000-strong Fastaqim Kama Umirt, a brigade aligned to the rebel alliance Jaish al-Mujahideen (Army of Holy Warriors).

Having withstood more than three weeks of Russian bombing and Assad ground assaults, the rebels say they are relieved they have lost little territory, just five villages in the southern Aleppo countryside.

They say Assad’s forces aren’t up to launching offensives on built-up urban areas. They suspect the Assad objective when it comes to the city of Idlib and the rebel-held portion of Aleppo is to encircle and besiege them, to starve them out, much as the regime did with Homs.

“Our fighters are skilled fighting in the towns and all we need are Kalashnikovs,” said Col. Mohamed al-Ahmed, spokesman of militia alliance Al-Jabha al-Shamiya (Shamiya Front). “The Assad regime knows it can’t fight in the city — so it is choosing to fight in the countryside,” added al-Ahmed, a Syrian Air Force pilot defector.

Battle pattern

For days now the battles have see-sawed, settling into a pattern of daytime regime advance and nighttime withdrawal, suggesting the skirmishes being fought around Aleppo and mirrored in similar big fights in the provinces of Hama and Idlib will be prolonged.

Two factors have been crucial for the rebels confronting the Russian-backed offensives that Iranian commanders helped plan: TOW anti-tank missiles and a surge in rebel recruitment.

Months before the Russian intervention, commanders lamented the difficulty in finding new recruits. That has changed, at least in rural areas.

Now locals are eager to fight, so, too, are youngsters among the refugee population in neighboring Turkey. Some recruits are as young as 15, something likely to prompt the condemnation of rights groups.

“Since the Russians came many people want to fight,” said al-Ahmed, sitting in a bare, dismal office in a ramshackle building adjacent to the wasteland in the Turkish border town of Kilis. “Before they said they didn’t want to kill fellow Syrians, but now they want to confront the Russians.”

TOW anti-tank missile

Charles Lister, an analyst at the Brookings Institution, estimates the use of the TOW missile has increased 850 percent since the Russian intervention began.

Rebels in Hama and Idlib have received large numbers routed through the Turkey-based Military Operations Center staffed by Arab and Western intelligence personnel, including CIA officials.

Who gets arms supplies is decided in concert by the so-called Friends of Syria in the MOC, 11 nations are represented and many Aleppo-based militias say they have been left out of the TOW supply chain. Before the Russian intervention, the Aleppo-based rebels were down to four TOW missiles between them.

TOWs have arrived in Aleppo, although not in the numbers rebels say they need, a source of frustration for them. But often they are brought over by battalions from militias in Idlib and Hama, a sign rebel infighting that has plagued the revolution, is for now being put aside.

No recent supply

Several militias approached by VOA, and widely reported as having TOWs, say they have not received any recently, including a once Western-favored group, Harakat Nour al-Din al-Zenki. “No, we don’t have any,” said Mohamed Mahmoud al-Saed, a militia spokesman.

The First Brigade in Aleppo is one of the few that has received TOWS.

Some Aleppo-based rebel commanders suspect the different treatment by MOC when it comes to them and militias in neighboring Idlib and Hama reflects disputes between U.S.-led international coalition partners over which militias to favor.

Falling afoul of MOC politics is a constant risk for the militias, but rebel commanders say this is not the time for either disputes between militias or for disagreements among the Friends of Syria.

“We need continuous supplies,” said Malahefji of Jaish al-Mujahideen.