Bullet-scarred and buttressed, Beirut’s Yellow House has lain dormant for decades, an indelible and often painful reminder of Lebanon’s recent history.

Once a marker of Beirut’s shift into the modern era, its sandstone confines became synonymous with death as a sniper’s den during the country’s civil war.

Yet, having escaped demolition, it is now set to begin a new chapter as a museum and research center and hopes are that in forcing its visitors to confront the past, it can help build a better future.

Horror and Hope

When Mona Hallack first entered the Yellow House she could scarcely have realized the role it would play in her life.

It was 1994, and Hallack stepped into a building that remained largely untouched since its notorious role during the country’s 15-year civil war, which began in 1975.

“I stood there, and in two seconds images of war flashed into my mind, memories of snipers, anecdotes of people being killed,” explained Hallack, whose subsequent tireless campaigning is the main reason the Yellow House stands today.

A crumbling shell, it stood on the crossroads of what was known as the city’s "Green Line"’ dividing the warring factions of east and west Beirut.

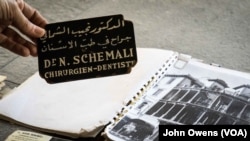

The detritus of families and businesses that had once made it their home lay scatted beneath her feet: school photos, letters from loved ones, reels of film from a photography shop.

These snippets of life contrasted starkly with more recent, and brutal, additions.

Sandbags that had once protected snipers lay untouched, while graffiti screamed from the walls, “Hell’, one read.Though Hallack saw horror, she also saw hope.

A murderous house

Built in 1924 for the wealthy Barakat family, (it is also known as the Barakat Building) its neo-Ottoman style offered a cutting edge innovation, an open entrance that plunged deep into the building, and a transparent design that spoke of wider cultural changes taking place in the city.

All this changed with the civil war. Once a blessing, its openness and prominent location between Damascus Street and Independence Street became a curse, allowing snipers unparalleled views over the area.

“It went from an avant-garde, innovative presence in the city to become a tool for killing, a murderous house,” explained Youssef Haidar, the architect tasked with renovating the building, now renamed Beit Beirut, before its re-opening to the public this Autumn.

Due for demolition in the 1990s, it was Hallack’s ongoing campaigning that raised the profile of the building, and eventually the municipal council stepped in to expropriate it in 2003.

Since then, Haidar has sought to retain the character of the Yellow House while introducing 21st century design.The pock marks, sniper’s bunker and graffiti now share space with an underground auditorium and towering glass facade.

Their efforts, and the efforts of those who have worked with them are focused on one thing, giving Lebanese a space in which to confront their past, no matter how painful.

Importance of remembering

“Some people don’t want to remember because they were too much implicated in [the war] either as actors or victims, but in both cases I believe that remembering is important,” explained Haidar.

Though the civil war ended, its echoes are felt in present day Lebanon, whether it is in a political class dominated by warlords from that era, or sectarian tensions that continue to bubble beneath the surface.

But the Yellow House’s history is far more than the war that came to define it.

Though buildings carrying the scars of this era are not hard to find, much of the old city has made way for lucrative high rise developments.

Hallack will be curating content in the museum, something she explained she hopes will focus on allowing people to "tell their stories."She said that in the drive to rebuild the city, something is being lost.

It is something that can be found in the striking architecture of the Yellow House, or in the remnants of life that were strewn across its floor.

“These aren’t just buildings, it is the traditions and quality of the lives of those who lived there that are being lost.This is what differentiates Beirut from Dubai or from any other city.”

“What is Beirut today? Now you have to go look for it, it’s not obvious any more.”

Looking to the future

The focus may be on addressing the past, but the power of the project lies in hopes that it can help shape the future.

Among those allowed to visit the museum before its opening were the family of Fouad Kozah, who, as a young architect in 1932, added two more floors to the work of Youssef Afandi Aftimos, the building’s original creator.

Though he lived to see it saved, Fouad died before work truly began on restoring and renovating his design.

His daughter, Nadine, hopes that younger generations will visit the building and learn from it as “a reminder of never again”.

For her, though, the re-opening represents a restoration of what the Yellow House is truly about, life, not death, what lies ahead, not what has gone before.

“Now we are going to turn the page,” she told VOA. “Instead of being prisoners of the past, we see it, but we don’t stop at it, we continue.”