In the early part of the 20th century, the chemical element radium was widely believed to cure a number of ailments. It also was used as a way to create glow-in-the-dark faces on watches and clocks. The case of several women who painted those clock and watch faces in a small town in the Midwest state of Illinois helped to raise awareness to the dangers of radium, and forever changed labor laws in the United States.

As a 12-year-old history student in rural Illinois, Madeline Piller’s friend introduced her to the story of a group of women from nearby Ottawa, Illinois, who worked at the Radium Dial factory in the 1920s and 1930s.

“I’d never heard of it. She’s like 'oh yeah it’s huge, but no one talks about it.' So if no one talks about it, it must be interesting,” said Piller.

Radioactive exposure

What no one talked about were the harmful effects to humans caused by exposure to the radioactive radium.

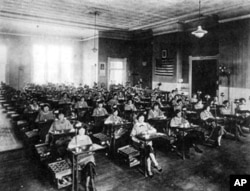

Young women in their late teens and early twenties were recruited to work at the Radium Dial factory in Ottawa. They painted the faces of watches and clocks with radium, which caused them to glow in the dark.

“The women were instructed to lick point their brushes before they would paint on the clocks,” said Piller.

By 1925, the management at Radium Dial was aware of the toxic effects of the chemical element, but failed to inform their employees, or take precautions against further exposure.

Harmful effects

Many of the women developed cancerous tumors, honeycombed and fragile bones, and suffered painful amputations.

“They were dying. The doctors were lying to them. The town was against them for protesting,” said Leonard Grossman, Jr., whose father, Leonard Grossman, Sr. was hired as an attorney to represent one of seven women, dubbed “The Society of the Living Dead,” which started a legal battle in 1934 against the owners of Radium Dial.

“It was such a dramatic form of workplace injury because the workers didn’t know for years that they were injured," said Grossman. "This was something insidious that was going on inside their bodies and the employers convinced them that this was good for them.”

The case of the "Radium Girls," which also included workers from a similar plant in New Jersey, traveled all the way up the legal system, reaching the U.S. Supreme Court.

The women eventually won, and received a modest settlement from the United States Radium Corporation, the parent company of Radium Dial.

Positive changes

Among many different ways their case affected labor law in the U.S., it led to changes in workers compensation, and the creation of radiation safety standards.

It should have closed a chapter to an unjust episode in the history of the small town of Ottawa, Illinois.

But many in the town blamed the women for the loss of jobs during the Great Depression. It soon became a taboo topic just as many of the "Radium Girls" were dying from their exposure.

“People didn’t want to talk about it too much," said Bob Eschbach, Ottawa’s mayor. "They thought it would give Ottawa a black eye, people might have the wrong impression, and they really kind of tried to sweep it under the rug.”

Residual damage

Eschbach said the town’s entanglement with radium didn’t end when the case of the "Radium Girls" settled in court.

The chemical element found its way into the soil and groundwater, contaminating residential and commercial properties around town.

The dangers of radium no longer was isolated to those who worked in the Radium Dial plant, or its successor, Luminous Processes.

After Luminous Processes closed in 1978, the vacant building stood as a radioactive reminder of Ottawa’s long history with the chemical element.

The town became the site of a costly “superfund” cleanup project of the United States Environmental Protection Agency in the 1980s. It demolished the existing Luminous Processes structure, and excavated the former location of Radium Dial, in addition to other sites across town.

“We had over a dozen radioactive sites, all of which are now cleaned up, but two, and we’re working on those. So I think when those things started to happen, attitudes started to change,” said Eschbach.

Now, in Ottawa, talking about the "Radium Girls" is no longer off-limits, thanks in part to the efforts of Piller.

“I was reading through a book and it said no monuments have ever been raised for the "Radium Girls." And that really hit a nerve with me, because these women, as not a lot of people know, set radiation standards that we use still today,” she said.

Honoring the 'Radium Girls'

Piller spent the last five years trying to raise money and awareness to build a permanent memorial, ensuring no one else forgets the story of the "Radium Girls."

A life-size bronze statue, created by Piller’s father, with a woman holding a tulip in one hand and a paint brush in the other, now stands in front of the former location of Luminous Processes.

“The scars that this put on Ottawa have healed. I want it to be an inspiration, I want it be a memorial for these women, something that we should never forget, because if we don’t talk about it, it’s as bad as forgetting,” said Piller.

A ceremony to dedicate the memorial this Labor Day weekend drew a crowd of hundreds - including Rose Baima, Pauline Fuller and June Menne - three of the few surviving employees from the Luminous Processes factory.

As Piller tries to help Ottawa heal the wounds caused by the deadly radium, the cleanup effort is not entirely over.

A contaminated site on the outskirts of town still needs to be remediated, a process that could take up to five years at a cost estimated over $80 million dollars.