Vladimir Putin confirmed last week he would seek a fifth term as Russia’s president next March — and this week, he kicked off his re-election campaign, not in his home country, but overseas in the Middle East.

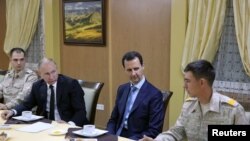

With stops in Egypt, Turkey and Syria, where he declared Monday that Russia’s military had accomplished its goal of saving President Bashar al-Assad from ouster, an upbeat Putin appeared eager to stoke national pride and showcase how he has restored Russia’s Soviet-era role as a serious power.

Putin’s re-election is assured — polls show an easy win for the man who has dominated Russian politics for nearly two decades — but he and his aides reportedly fear voter apathy and seem determined to secure a large turnout in March and a big legitimacy-boosting vote.

Cutting a figure on the world stage as a power broker, and showing off a new set of friends from the shores of Tripoli to the Persian Gulf, play well at home, say analysts.

Russian state media lavished round-the-clock coverage of his whirlwind trip from his plane as it flew escorted by Russian jet fighters into Syria, and from the ground as he was thanked by Assad at a Russian military base - as well as in Cairo, where he signed a deal for the construction of a nuclear reactor on Egypt's Mediterranean coast. It also was the case from Ankara, where during a news conference to mark their eighth meeting, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan kept referring to Putin as “my dear friend.”

In Syria, Putin said ‘mission accomplished’ regarding the Russian rescue of Assad, providing him with the opportunity to announce a partial withdrawal of Russian forces from Syria.

Praising Russian troops at the Hemeimeem air base in Syria, Putin talked of their triumph, declaring in remarks broadcast in Russia: “You have shown the best qualities of a Russian soldier — courage, valor, team spirit, decisiveness and excellent skills. The Motherland is proud of you.”

He made no mention, though, of the civilian casualties from indiscriminate Russian airstrikes — or that his intervention has helped to prop up a blood-soaked dictatorial regime by critically weakening the armed non-jihadi opposition to Assad.

Since September 2015 when Putin launched his military intervention in Syria, Russia’s profile in the Middle East has risen, defying early Western predictions that involvement in the tangled Syrian conflict would result in disaster for Moscow.

Then-President Barack Obama’s defense secretary, Ash Carter, predicted Putin’s mission was “doomed to failure,” arguing Russia would be caught in a Vietnam-style quagmire.

That didn’t happen — or not so far.

Putin’s plunge into Syria was prompted initially by his suspicion that Arab spring-era uprisings were Western-fomented - insurrections aimed at unseating strongmen and dictators that could spread to Russia, according to Dmitri Trenin, author of the new book What is Russia up to in the Middle East?

“To Putin, all this looked like an Arab rerun of the ‘color revolutions’ that swept across the old Soviet buffer, from Georgia to Ukraine. Sparks from Arab revolutions could ignite Russia’s geopolitical underbelly,” writes Trenin.

And tactical success has turned the Syria intervention into a cornerstone in Putin’s broader ambition for Russian influence, according to analysts, allowing him to expand Moscow’s sway in a region where the U.S. is perceived now as eager to shrink its role and avoid messy entanglements.

Seizing on U.S. setbacks and missteps, the Kremlin has clawed back some of the Soviet Union’s former clout in the Middle East, allowing him, much as his Soviet predecessors, to project global influence and military might and to amass bargaining chips for negotiations with the West in other disputes.

Moscow has “emerged from its military engagement in Syria with the most connections in the region,” Trenin argues, while nimbly avoiding “falling into the cracks of Middle Eastern divides: Shia versus Sunni; Saudi versus Iran; Iran versus Israel; Turkey versus Kurds.”

Putin has been courting traditional U.S. allies in the region, including Saudi Arabia and even Israel. He received more leaders from the Middle East in Moscow than Barack Obama did in the last two years of his presidency and his meetings with the region’s leaders have continued apace during Donald Trump’s first months in the White House.

How long Russia can continue to avoid the treacherous cracks remains to be seen.

Retired U.S. general Colin Powell famously remarked once, “you break it, you own it.” Putin will own Syria but the hostility involving embittered sectarian foes may be impossible to manage. Russia’s balancing act between the Kurds and the Turks will be difficult to maintain, and Iran’s agenda for Syria, Lebanon and Iraq may over time clash with Russia’s, as well as the Kremlin’s eagerness to cosy up to the Saudis.

“The war in Syria is not over. The fragmented territory today, foreign military occupations, and conflicting political agendas might lead to new confrontations,” says Ziad Majed, a French academic and author of the book Syria: The Orphaned Revolution.

In Libya, Russia has been seeking a greater role with a possible ambition to add a naval facility there to the one it will maintain in Syria, say analysts. Russian diplomats and generals have been courting Gen. Khalifa Haftar, who has made little secret of his desire to rule the strife-torn North African state.

And Russia has been inserting itself into the Israeli-Palestinian peace process. Last year, Putin offered to host peace negotiations in Moscow between the Israelis and Palestinians. This week, the Russian leader was quick to pounce on U.S. President Donald Trump’s decision to recognize Jerusalem, the third holiest city in Islam, as Israel’s capital, upending decades of American diplomacy and breaking ranks with the international community.

The U.S. move "doesn't help the Mideast settlement and, just the other way around, destabilizes the already difficult situation in the region,” Putin said during a news conference in Ankara with Erdogan, who has been one of the most outspoken critics of the U.S. plan to move its embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

As U.S. diplomats have learned over the years, attempting to resolve the standoff between Israel and the Palestinians is a challenging task.