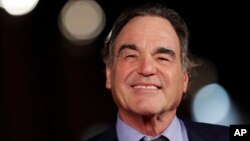

As the dust from Oliver Stone’s politically explosive (or not, depending upon which American you ask) “Putin Interviews” begins to settle, Russian viewers were just finishing the concluding episode late on Thursday.

In the United States, where the controversial series—four hourlong episodes—was made available to Showtime subscribers June 12-15, critics largely panned it as blatantly hagiographic.

“Natural Born Buddies: The Shared Ideology of Oliver Stone and Vladimir Putin,” wrote the left-leaning New Republic; “Oliver Stone stinks” was the blunt summation of conservative Daily Caller blogger Jim Treacher, who described it as one of the only times he saw eye-to-eye with Stephen Colbert, whose nationally televised grilling of the legendary filmmaker for being overly deferential to Putin became a story unto itself.

In Russia, however, where the documentary held consecutive prime-time slots June 19-22 on state-run Channel One public access television, the response has been more muted. Putin supporters learned little new information, while detractors predictably took to the blogosphere to castigate Stone—whose son Sean works for RT, they repeated several times—as an instrument of the Kremlin’s PR machine.

Putin critic

Karen Dawisha is not known for putting softball questions to Russia’s leadership. Her 2014 book, Putin’s Kleptocracy: Who Owns Russia, was dropped by Cambridge University Press when the London publisher announced it couldn’t afford the legal risk of putting it into circulation. The book, her sixth major published work on Russian policy and leadership since 1979, traces a deeply intertwined network of Russian secret police, Mafiosos and powerful oligarchs to the twilight of Soviet empire.

Dawisha spoke with VOA’s Oleg Sulkin about how to gauge the impact of Stone’s work.

Editor’s note: Whether language translation was the only editorial distinction between respective versions of the documentaries aired in the United States and Russia has yet to be confirmed. The following transcript has been edited for brevity and concision.

Q: You watched the entire series?

A: I did watch all four, although the third one, when Stone said that he wanted to have a lengthy discussion about Ukraine, and Putin said, “Well, for this, I need to start from the beginning…” That’s it. I immediately fell asleep. You tell me, did he say anything new or interesting about Ukraine?

Q: Nothing surprising, which seems to characterize the whole project. There were no challenging questions put to the statesman, and I wonder if you think it’s appropriate for an American filmmaker and observer to be so toothless in the face of such an unusual opportunity.

A: Well, look, Oliver Stone has a reputation for always, no matter what the circumstances, finding the United States as the villain. So it makes for not very interesting viewing, unless you’re someone like [she names a well-known U.S. scholar sometimes seen as being supportive of Putin], and then you are very excited that Oliver Stone has basically hit the United States with some big revelation. I watched it because I think people should watch these things. [Stone] got four nights on American television, and that’s not so bad. But, boy, he didn’t produce anything that was very earth-shattering at all.

Q: Stone has described softball questions as a strategically efficient way to deal with people like Putin. To start with soft, complimentary questions that get the subject to open up before setting in with more incisive questions. But do you think it worked?

A: Well, I mean certainly, in foresight, that day when he went again and again to the subject of the hacking of the election, it did seem that Stone had this approach. But he also didn’t push him, so I came away thinking, “It’s just the same thing, there’s no major revelations. … What did we learn about hacking that I couldn’t learn from reading The Washington Post?”

Q: But some people commend Stone for these Putin interviews for securing some new minor details about one of the most influential and dangerous people in the world. For example, it was the first time Russia found out that he is a grandfather, which sheds some new light on the dictator’s inner world.

A: But grandkids by whom? Which daughter?

Q: We don’t know. We learn only that he doesn’t have enough time to play with the grandkids.

A: Exactly. We learned this, and the Russian press is very happy for this small revelation. But this shows you how little we know about Putin. That he didn’t give us any revelations about any other aspect of his life. I reckon that I did find it interesting [to see] his physical surroundings. The pictures of him in Sochi, the picture of him in the Kremlin.

Q: But as an expert researcher, aren’t even small new details useful for composite assessments? More specifically, do you think it will help create a more favorable impression of Putin among American viewers?

A: Well, I haven’t seen any information about how many people turned it on. … But clearly there will be more people in Russia who watch [because it’s on public access television] than watched in America. But it shows you that, on the whole, Putin was very happy with the propaganda aspect of this series. And look, Stone is a very good filmmaker, so these four interviews were visually very pleasant. I mean, there are good shots; no one can complain that he doesn’t know how to make a film. But as we’re getting ready for [Russia’s] next presidential election, don’t you think this will be very helpful to Putin? To have Oliver Stone legitimize his rule? I think that it’s not bad for Putin.

Q: You feel it would have been more appropriate to feature people who could argue with Putin? Like the opposition leaders who could counter Putin’s statements about Russian freedom, such as his claims about the freedom of Russia’s press, and so on?

A: Well, yeah. But would Putin have agreed to such terms? [Currently detained Russian lawyer, activist and presidential opposition candidate Alexei] Navalny is infinitely more interesting on television than Putin. But would Putin agree to interview on those terms? I don’t think so.

Q: And we can only speculate about whether there was some kind of a confidential deal that would allow Putin’s camp to have a hand in the final edits. Only four of 25 hours of footage is seen. Otherwise, would Stone have even been granted this level of access?

A: Exactly. I mean, they made a big deal of the fact that there was no limitation on what questions Stone could ask. But that doesn’t mean at all that there were no limitations of any kind. So, why did Putin agree at all to this? Certainly not because he wanted to debate Navalny and win against Navalny. I don’t think that would have for a second been possible, not for a second. He would never agree.

Q: Which touches on a very important question: Why did Putin agree in the first place?

A: Yeah. I mean, Stone doesn’t get this at all.

Q: But why would Putin even agree? What’s your personal assessment?

A: My own assessment is that Putin has a big problem with his image in the West. He has a huge problem with multiple rounds of sanctions, and now [very likely] a third set of sanctions. He needs to do something to get his sanctions lifted, because they are really hurting his economy. And what Stone said … [about] how well the Russian population is doing under Putin, that’s completely wrong. And of course Putin was thrilled that Stone should come up with these numbers, because they don’t reflect at all what Russia’s actual figures are. … Russia is doing much worse than [Stone’s] figures would suggest. And we saw that in the recently aired, annual call-in program. … the Russian population was very blunt and very forward in calling out Putin on how poorly they were doing in terms of wages and salaries, and saying things that were put up on the board behind him. Like a question: “Why is it that you are on the throne for 16 years? That’s too long!” … Stone talked about the overall figures for Russia’s wealth — $29,000 a year average income. But that doesn’t account for the fact that most Russians are earning way below $29,000. They’re earning more like $12,000. Teachers, health workers, all of these people who are at the lower end of the scheme. They earn poverty wages.

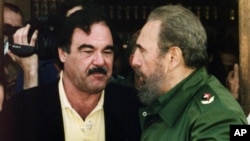

Q: Regardless of whether that misinformation is deliberate or incidental, it inevitably advances an apologetic view of the Kremlin. So, for Stone, was it all a vanity play? To show he’s on friendly terms with the most powerful people in the world? Some would argue Stone used that same obsequious approach with Fidel Castro, Evo Morales, Hugo Chavez.

A: The thing that I noticed, especially in the first interview, was that Putin was constantly being polite, not saying anything very negative about the United States. After all, his No. 1 goal is to get the sanctions lifted. He’s not going to give a very robust criticism of the United States under these circumstances. But what did Stone do? He basically offered to Putin the anti-American answer, [saying], “It was the intelligence services of the United States, they’ve made this all up.” Stone was offering up a kind of leftist argument to Putin, and Putin is no leftist. He doesn’t have an interest in this kind of response, you know? He has an interest in getting Trump to open up his channel of communications between the United States and Russia.

Q: On NATO, Putin spoke about the dangerous course of politics they’re pursuing. Do you think it gives an idea of his real concerns or is it just a way to argue with the United States?

A: I think it’s his real concern. Look, he stated once that the Soviet Union collapsed [because of] American military spending. Basically, that was his point of view. Well, why might Russia collapse now? American military spending. He stated several times, and it’s true, that the United States spends more on its military than all other countries combined. So the essence [of Putin’s argument] is that NATO’s new military systems positioned close to the Russian border and its commitment to Article Five, are dangerous steps. Having said that, the Russians have behaved in a very reckless manner. You know, their behavior in Georgia, their behavior in Ukraine was reckless. Although, I will say Russia has a situation in which in both Georgia and Ukraine are now territorial problems, making it so that neither country would be qualified to join NATO, because they have active territorial disputes. So NATO creeping toward the Russian border is a huge issue for Russia.

Q: These hearings about Russian meddling in U.S. elections: What’s the bottom line? Are Stone’s interviews just a propaganda trick? Is Stone just following the Kremlin’s discourse?

A: There is a completely different training of world events in Moscow as compared to Washington. When I watched the fourth part, I understood very clearly that Moscow has its point of view, and it’s pretty much in accord with Stone’s point of view. … There are people in the West that agree with Putin … [including] specialists on Russia, like former [U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union] Jack Matlock and [the aforementioned U.S. scholar]. They really think that America is in the wrong, and that it is imperative that the United States improve its relations with Russia, and that there is no way that the United States is right. I listened to a Jack Matlock lecture on the radio here in Cincinnati yesterday, and one of the things he said was that the intelligence community of the United States was wrong. And I really couldn’t believe it. That the 17 intelligence services were all wrong and made this up. You have to have a very extreme point of view to think that 17 intelligence services are in collusion to make this up. But there are people in the United States who have this point of view.

This report originated in VOA’s Russian Service.