Five years ago this week, tanks rolled into the streets of Ankara and Istanbul, and soldiers ordered a news anchor at Turkey's state broadcaster, TRT, to read a statement announcing the military had seized power.

The coup attempt was shut down quickly. But for the country's media and voices of opposition, July 15, 2016, spurred an era of accusations and arrests, including the arrests of journalists who had covered events that night.

One of those was Ilhan Tanir, then Washington correspondent for Turkey's oldest newspaper, Cumhuriyet. Tanir recalls watching the coup unfold from the U.S., with TV stations interrupting regular programming to show military vehicles on Istanbul's iconic Bosporus Bridge.

"At the time, there were a lot of ISIS attacks in Turkey," the journalist told VOA, referring to the Islamic State terror group. "The rumors and the tweets were talking about how it could be some kind of ISIS attack."

But, Tanir said quickly, "we understood there was a coup."

In the hours that followed, Tanir used Twitter to convey information from Turkish sources to his English-speaking audience.

Months later, Turkish prosecutors claimed his earlier social media posts and news reporting were evidence that Tanir belonged to the Gulen movement, the group accused of orchestrating the coup.

WATCH: Failed Coup Attempt Changed Turkish Media Landscape

It was an accusation leveled at other journalists too. In the past five years, record numbers were arrested, often on accusations of supporting or producing propaganda for a terrorist organization. Authorities tightened control over digital and social media and forced some news outlets to close or come under new ownership.

At Tanir's outlet alone, at least a dozen journalists, including former Editor-in-Chief Can Dundar, were accused of being part of the Gulen movement, a grassroots religious organization led by Fethullah Gulen.

The 80-year-old cleric, who lives in self-imposed exile in the U.S., denies any involvement.

Addressing his party's provincial heads on July 8 of this year, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan described the failed coup as "one of the most treacherous attempts in our history."

The attempt to thwart democracy left around 250 people dead and more than 2,000 injured. Erdogan said that it had been carried out by Gulenists but had "a much wider network behind it."

Turkey has also dismissed international criticism of the arrests of critics and reporters. In a 2017 BBC interview, Erdogan denied that scores of journalists were imprisoned, saying only two with the official press card were detained.

A spokesperson for the Turkish Embassy in Washington told VOA via email that the allegations and criticisms were “based on biased information that do not merit any serious consideration.”

“We expect a basic understanding of the suffering Turkey as a nation faced five years ago on this day when members of the Fetullah Terrorist Organization (FETO) attempted to overthrow the democratically elected government in Turkey, bombed the Turkish Grand National Assembly and fired on the civilians,” the statement, emailed Thursday, said. “We believe that the friendship between democratic nations requires solidarity against such attacks, targeting the very fundamental principle of democracy."

VOA had reached out to the Turkish Foreign Ministry, the Presidency's Directorate of Communications and the Ministry of Justice in late June and earlier this month for comment but received no response to its requests.

From friend to foe

The Gulenists are former Erdogan allies who used to hold prominent positions in the military, judiciary and parliament.

But that changed in 2013, during a corruption investigation into Erdogan's close allies, which pro-government supporters believed was a Gulenist attempt to take over the government. Erdogan, who was then prime minister, accused the Gulenists of forming "a parallel state."

In May 2016, two months before the coup, Turkey officially designated the movement a terrorist group, calling it the Fethullahist Terror Organization.

Early on, Erdogan described the failed coup as a "gift from God" and promised "a new Turkey" — a statement analysts interpreted as a signal that the president would expand his crackdown on critics and political opponents, regardless of their involvement.

"It wasn't just members of the Gulen movement that were targeted at the stage," said Merve Tahiroglu, the Turkey program coordinator at Project on Middle East Democracy, or POMED, a Washington-based research and advocacy group.

"It was also people who had nothing to do with this movement. Many Kurdish outlets were among the first media outlets that were shut down by decree in the state of emergency," she said. "And we saw a lot of journalists, particularly Kurdish journalists but also liberal voices, progressive voices, get detained or sacked from their jobs."

For some, the accusations appeared to stem from being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

On the day of the coup, Henri Barkey, a Middle East expert and professor of international relations at Lehigh University in Pennsylvania, was on Istanbul's Buyukada Island, speaking at a workshop on Iran's relations with its neighbors.

But Ankara saw the American analyst's presence in Istanbul differently. It issued an arrest warrant for Barkey, and pro-government newspapers described him as a CIA operative working inside the country to topple Erdogan.

"It has been very costly to me, this Turkish accusation," said Barkey, who denies the allegations.

"I can't go to Turkey, obviously, to do my research there. People avoid me. Friends of mine have stopped talking to me because they are afraid, because any association with me is problematic and can be used against them," he told VOA.

Reuters reported that by 2017, more than 120,000 people had been sacked or suspended from government jobs for alleged affiliation to the movement, and over 40,000 had been arrested.

Analysts say those numbers are higher today and include prominent politicians such as Selahattin Demirtas, the co-leader of the pro-Kurdish Peoples' Democratic Party, or HDP, who has been behind bars since November 2016.

Last month, the Turkish Constitutional Court ordered HDP to go on trial for alleged links to the banned Kurdistan Workers' Party, or PKK. If connections are proven, the HDP will shut down like all the other pro-Kurdish parties preceding it.

Ankara's actions have resulted in media watchdogs labeling Turkey as the worst jailer of journalists.

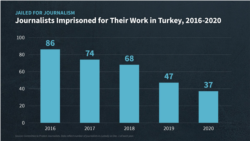

By the end of 2016, at least 86 journalists were jailed in Turkey, according to the New York City-based Committee to Protect Journalists, which tracks arrests linked directly to working as a journalist.

CPJ's annual prison census, which reflects the number of detained journalists, continued to show high figures in the years following the coup: 74 in 2017, 68 in 2018 and 37 at the last count, in late 2020. Alongside its snapshot of arrests, the press freedom organization flagged Turkey's "revolving door" approach of detentions, releases, and rearrests.

The European Union has also warned Turkey that its aspirations for membership hang on the country ending its authoritarian practices.

"Human rights, the rule of law, democracy, fundamental freedoms — including media freedom — are all basic imperative requirements for any progress towards the European Union," Johannes Hahn, the EU's membership commissioner, said after talks with Turkey in 2017.

'Abusing Interpol'

Journalist Tanir says he considered himself lucky to be outside of Turkey in 2016 and therefore able to avoid arrest.

Court documents accused him and his colleagues of additional crimes: undermining the Turkish state and supporting the PKK. The armed Kurdish group, which is seeking autonomy, has been designated a terrorist organization by both Ankara and Washington.

Tanir denies any association with either the PKK or the Gulen movement. But he is still wanted internationally because of a "red notice" arrest warrant that a Turkish court issued to Interpol in 2018.

"This has made my international travel impossible," he said.

Experts, including analyst and former lawmaker Aykan Erdemir, have said Turkey has a reputation for "abusing" Interpol for political reasons.

Inside Turkey, journalists have long been tried under counterterrorism laws and Article 301 of the penal code, which carries sentences for "insulting Turkishness," said free speech lawyer Veysel Ok.

"These were always the Sword of Damocles hanging over the heads of journalists, intellectuals, and writers," he told VOA, adding that before 2016, "in general, this pressure mainly was on Kurdish journalists, Armenian journalists, or journalists and media outlets with left or liberal views."

But after July 15, 2016, "this pressure has begun to be applied to everyone," Ok said.

"From the mainstream media to the (Gulen-affiliated) media, from the left media to the right media, everyone who thinks differently from the government, writes differently, and expresses an opinion other than the official view of the government has become a victim of the government," he said.

Ok, who is vice president of the Media and Law Studies Association, an Istanbul-based nonprofit offering pro bono representation for journalists, estimates that since 2016, more than 400 journalists have been detained.

In many cases, prosecutors "present news as evidence" when accusing journalists of charges such as membership in terrorist organizations, Ok said.

"As a journalist, you should have the right to talk to everyone while you are reporting. In other words, in the conflict between the parties of the conflict — for example, the state and the PKK — you should be able to ask questions to the other side. The state perceived it as … propaganda," the lawyer said.

Tahiroglu, of POMED, also says the media were under pressure before July 2016. "But we saw it expand considerably after the coup attempt, both in terms of scope and the impact that it had, I would say, on civil society."

The arrests were seen widely as a message to critical media, but some journalists said they had received more subtle signs that their work was not welcome.

In 2016, Hayko Bagdat was working as an Istanbul-based columnist for Diken, an independent news website. Before that, he contributed to news outlets including Taraf, a liberal daily that the government closed following the coup attempt, and Bugun TV, which had been seized in 2015 over its alleged links to Gulen and later closed. He also contributed to IMC TV, a pro-Kurdish TV channel shut down by the government following the coup.

Shortly after Turkey declared a state of emergency — a measure that remained in place for nearly two years — Bagdat traveled to Greece. He stayed for about three weeks, waiting for things to calm down.

On his return, Turkish border authorities seized his passport without explanation, he said.

When authorities returned his passport six months later, Bagdat, who is of Armenian descent, saw it as a gesture.

"Getting the passport back means 'leave,'" he said. "I knew it. The Turkish state's messages are always subtle."

Weeks later, Bagdat left for Germany, and his family later joined him. A new arrest warrant was issued, and because of that, the Turkish Consulate in Berlin refuses to renew the family's passports, Bagdat said.

"I have not been able to get my children on the plane for two years. So, they are staying in the city with an expired passport and a residence permit issued by the Germans. This is a serious problem," Bagdat said.

The Turkish Consulate in Berlin did not return VOA's request for comment.

Effect on Turkey's media

The arrests and harassment have had far-reaching impact on Turkey's media scene.

Media lawyer Ok said that prominent media outlets, including pro-Kurdish or those deemed close to the Gulen movement, had been closed and mainstream media put under new ownership.

Journalists looked to new avenues for independent reporting, including social media platforms. But changes to regulations regarding digital news and social media have led to further obstacles.

Ankara enacted social media regulations requiring that Twitter, YouTube and Facebook have offices in Turkey and respond to takedown requests quickly or risk fines.

The Radio and Television Supreme Council, which provides licenses and serves as a watchdog for the country's broadcasters, has been accused by Human Rights Watch of imposing "punitive and disproportionate sanctions against independent television and radio channels that broadcast commentary and news coverage critical of the Turkish government."

Turkey more recently issued a directive banning police from being photographed at protests, a measure it said was to protect the officers' privacy.

Lawyer Ok described the ban as "unconstitutional."

Changes in the application process for the press cards that give journalists access to official briefings have also proved challenging, with several journalism organizations saying the Directorate of Communications no longer issues accreditation for those at independent or critical outlets.

"When the process is not treating journalists equally, this hurts people's right to be informed. Because if you separate certain journalists, critical journalists, critical outlets from others and make the fieldwork harder for them, this is censorship from whichever angle you look at it," said Ozgur Ogret, the Turkish representative for CPJ.

With Cumhuriyet under different leadership, former Editor-in-Chief Dundar has started a new website from Germany, where he lives in exile.

The website, called Ozguruz, which means "we are free" in Turkish, covers events in Turkey and Germany, but access to the site is blocked in Dundar's home country.

Last year, the veteran journalist was sentenced in absentia to more than 27 years in prison for espionage and aiding a terrorist organization.

Tanir also no longer works for Cumhuriyet.

But even his employer — Ahval, a news website that covers Turkish politics and economics — has faced accusations of Gulen links. Something that Tanir and the media outlet deny.

Tanir said that while covering the U.S. State Department, he had been one of the first journalists to question the so-called Gulenists' alleged involvement in human rights abuses and pressure on the media in the early 2000s.

"Anyone can go and look at the archives of the State Department and see who asked most questions about the human rights and press issues (in Turkey) when the Gulenists were powerful and ruling the country indirectly with their allies in the government," he said.

"The record is out there, but once the Turkish government wants to punish a critical journalist, they always find a way."

Umut Colak contributed to this report from Istanbul.

Editor's Note: This report has been updated to include a response from Turkey's Washington Embassy to allegations and criticism that it retaliates against the media and critics.