For the Voice of America news executive who made the fateful decision, the scoop was too extraordinary and important to pass up.

Just 10 days after the September 11 attacks on the U.S. that killed 2,977 Americans and injured countless others, Osama bin Laden's closest ally and protector in Afghanistan – the reclusive Mullah Omar – offered VOA's Pashto service an exclusive interview.

Myrna Whitworth, the acting director of the Voice of America at that time, assigned two journalists to interview by phone the mysterious Taliban leader who had permitted bin Laden, the 9/11 mastermind, to take up residence in Afghanistan.

But Bush administration officials soon learned that VOA was preparing a story. Whitworth received a call from the State Department and was told it would be "political suicide" if she aired the Omar interview.

While the Bush administration "respected the agency's right to report news objectively," officials didn't want VOA to "do things that we thought were going to be a comfort for the enemy," Richard Boucher, the State Department spokesman at the time, said in a recent interview.

VOA, the government funded, global multi-media broadcaster, provides service in more than 40 languages to as many as 280 million people a week. It has a storied history dating back to World War II and a mandate from Congress to impartially and comprehensively report the news.

But tensions between the White House and VOA have been the norm for decades, largely because of the uniqueness of a semi-independent – and occasionally aggressive – news agency operating within the belly of a massive federal government bureaucracy.

Last month, President Donald Trump joined some of his predecessors who have taken issue with VOA's news coverage – but with unprecedented intensity and shrillness.

"If you heard what's coming out of the Voice of America, it's disgusting. What – things they say are disgusting toward our country," Trump said during a coronavirus news briefing in the Rose Garden on April 15th.

Trump's complaint essentially was two-fold: First, that the VOA had used dubious Chinese government data on the coronavirus infections and deaths in China in its reporting – an accusation vigorously disputed by the news organization.

And second, the president was irate that he had been unable to install a new head of VOA's parent organization – the U.S. Agency for Global Media – for over two years because of Democratic obstacles to confirmation in the Senate.

Trump has lamented before that he lacks control of a government-owned media outlet that reflects his values and those of his supporters. Last November, Trump suggested that the U.S. should create a state-run, global news network to counteract what he calls "unfair" and "fake" coverage from CNN and to show the world how "great" this country is.

However, as the Mullah Omar interview and other examples illustrate, Trump is not the first president to criticize VOA's news coverage. That is because while the media organization is usually overseen by White House political appointees, the news content of its career journalists is required by law to be unbiased.

A government broadcaster's editorial evolution

The White House and State Department declined a VOA request to expand on the president's televised criticisms or on separate allegations detailed in a White House newsletter earlier this month, that accused VOA of amplifying Chinese propaganda in its use of data during the coronavirus pandemic.

VOA Director Amanda Bennett rejected the charge and said the agency "strives to do objective fact-based reporting that doesn't amplify anybody's message."

Indeed, VOA has debunked Chinese misinformation nearly 20 times, according to the Reporters Committee, a freedom of the press advocacy group.

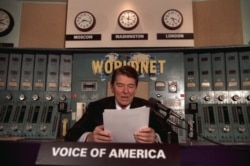

This straight down the middle editorial approach was not always VOA policy. After the agency was created in 1942 to combat Nazi propaganda with objective news, for its first decades VOA reporting was subject to approval by government minders.

During the Kennedy-era Cuban missile crisis of 1962, VOA was essentially "operating under government supervision," said, Nicholas Cull, professor of public diplomacy at the University of Southern California Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism and author of "The Cold War and the United States Information Agency."

"There was an administrative officer sent from the supervising U.S. Information Agency over to VOA," Cull said. "He had to approve every script."

That approach faltered during the Watergate scandal that led to President Richard Nixon's resignation in 1974. Cull said that VOA journalists who insisted on giving a full picture of the investigation into the president's alleged wrongdoing ran into opposition from USIA officials who wanted a more positive story.

The journalists wanted to turn Watergate into an "on-air civics lesson showing that the strength of America lay not in its president never making a mistake, but in the ability of its Congress to correct that mistake through due process," Cull said. In the end, a compromise was reached that every time a negative story was carried about the president, a positive story had to be carried as well.

"This led to some kind of weird broadcasts," said Cull. "They'd be saying, in news today the President was named as an unindicted co-conspirator in the Watergate crisis… and Mrs. Nixon opened a new kids' school in Washington DC."

A news agency barred from showing bias

By 1976, Congress and VOA executives determined the agency needed a clearer editorial mandate to ensure that it maintained credibility with overseas audiences. Congress drafted the Charter, which says VOA must publish accurate news; produce content that represents all of American society; and provide clear explanations and discussions of U.S. policies.

The long-range interests of the United States are served by communicating directly with the peoples of the world by radio. To be effective, the Voice of America must win the attention and respect of listeners. These principles will therefore govern Voice of America (VOA) broadcasts:

Gerald R. Ford

President of the United States of America

Signed July 12, 1976

Public Law 94-350

The agency's editorial practices were further defined in legislation in 1994 and 2016, which specified measures to shield journalists from political influence and called for the agency to uphold the "highest professional standards of broadcast journalism" while remaining consistent with the "broad foreign policy objectives of the United States."

Richard Stengel, a former editor of Time magazine and former undersecretary of State for Public Diplomacy in the Obama administration, said this independence is what distinguishes VOA from some of its competitors.

"VOA is not the state broadcaster of the United States the way state TV in authoritarian countries have to reflect the foreign policy goals or principles of that country. It's not what North Korea does, or China does, or Cuba does, or places like that. It's an independent broadcaster and part of the reason that VOA is followed and admired by millions of people around the world," Stengel said.

US broadcasting, White House-approved executives

While VOA's journalists are required to produce objective news, the agency is under the authority of the executive branch, which has the power to nominate a Chief Executive Officer for VOA's parent agency, the U.S. Agency For Global Media.

USAGM oversees five federally funded public service media networks that provide news to countries where the press is restricted. The CEO of USAGM, along with a bi-partisan board of media executives and international affairs experts, appoint the heads of the media networks, including VOA.

Trump nominated Michael Pack, a conservative documentary film producer and media executive, as chief executive officer of USAGM in June 2018.

Democratic Senator Bob Menendez of New Jersey recently wrote the White House saying Pack has yet to answer committee questions about allegations of self-dealing in his businesses, past income tax statements, and alleged "negative circumstances" around his departure from a previous job.

A spokeswoman for Pack told VOA he was declining to comment for this story, due to the ongoing nomination process.

Clifford May, head of the Washington think tank, Foundation for Defense of Democracies, said Trump's criticism of VOA is warranted because of his frustration over getting his nominee approved.

May characterized VOA Director Bennett as a holdover from the administration of Democratic President Barack Obama, who has failed to adequately explain the Trump administration's policies to the world.

"That should be explained on VOA – if not there, where else? That doesn't mean there can't be op-eds, or criticism of the president as well. All those things can coexist in a balance. It takes good journalists to do that," May said. "It's clear that this administration thinks it's not being done properly by those who are now in charge."

Bennett, a former Bloomberg News executive and editor of the Philadelphia Inquirer, was named Director of the Voice of America in March 2016 and has continued to oversee the agency into the Trump administration.

During the 2001 dispute involving the Mullah Omar interview, more than 100 journalists at VOA spoke out, signing a petition urging the agency to resist the pressure. VOA ended up airing segments from the interview and released a statement defending the coverage to its critics. "The people in Afghanistan are tuning into us because they trust us, and we tell the whole story," the statement said in part.

Boucher, now a foreign policy professor at Brown University, said that both sides later "moved on" from the clash. Yet less than two weeks after the interview aired, Whitworth was moved from her position as acting VOA director and replaced by White House appointee Robert R. Reilly.

"The pressure was not blatant but they did make it clear I was to have no further role in editorial decisions," said Whitworth, who was a career journalist at the agency, not a political appointee. She decided to retire early.

A government broadcaster that navigates political tension

Periods of divisive politics in the United States, such as a presidential impeachment or war, can put VOA in a difficult position, said Lata Nott of the Freedom Forum. But those are also the times she says the broadcaster builds credibility with its audiences.

"The fact that our federally funded media organizations are not state-run media, but independent is incredibly important," Nott said.

"It's in the nature of a government to say we're paying for this, we want to have our best story told," said USC professor Cull.

"But it's in the nature of journalists to push back and say the ethics of journalism involve telling both sides of the story, and to be effective, we have to be credible."

Since its 1942 inception to combat Nazi propaganda and despite subsequent legislation that protects the VOA newsroom's editorial independence, the agency has fought its own battles to maintain its independence. Here are several examples:

- In the early 60s, VOA cannot broadcast about the Cuban missile crisis without approval from the United States Information Agency (USIA), its overseer organization at that time.

- While covering the Watergate scandal that lead to President Richard Nixon’s resignation in 1974, VOA clashed with USIA officials who wanted a more positive spin on the story. A compromise was reached that every time a negative story was carried about Nixon, a positive story had to be carried as well.

- During the George H.W. Bush administration, USIA tried to block airing of VOA’s interview with Fang Lizhi after the Chinese dissident came to the U.S. in 1990. Fang had taken refuge at the U.S. Embassy in Beijing and part of the deal to allow him to leave the country was that Washington would not “exploit” his story.

- A similar affair happened in 1997 when the Clinton administration helped secure the release of Wei Jingsheng and tried to block the airing of VOA’s interview for fear it would jeopardize the future release of dissidents.

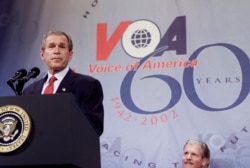

- Weeks after the 9/11 attacks, the State Department under George W. Bush’s administration tried to block the airing of an exclusive interview with Taliban leader Mullah Omar, who had permitted Osama bin Laden to take up residence in Afghanistan.

- Discussions of "VOA’s post-911 role" continued after the agency aired a portion of the interview. Some officials within Barack Obama’s administration voiced concerns that the agency’s reporting did not reflect U.S. foreign policy priorities against violent extremism.

Sources: VOA staff interviews; Nicholas Cull, The Decline and Fall of the United States Information Agency: American Public Diplomacy, 1989–2001, 2008; Alan L. Heil, Jr, Voice of America - A History, 2003.