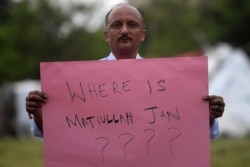

A prominent Pakistani journalist known for his harsh criticism of the military and the ruling party was seized from the heart of the capital, Islamabad, and held for 12 hours Tuesday, according to his family.

A brother of the journalist, Matiullah Jan, confirmed to VOA shortly after midnight that Jan had been released. Details of his detention were not immediately available.

CCTV footage shows a group of men, some in plain clothes, others in black uniforms used by elite counter terrorism units of the police, forcing Matiullah Jan into a car as he resisted.

During the scuffle, Jan, who was parked outside a school where his wife taught, threw his mobile phone inside the compound. One of the men in uniform walked over to the closed gate and asked people standing inside to hand the phone back.

“The teacher standing with me handed the mobile to him. We thought a thief was running with the phone and the police were following him, so he threw the phone inside. We heard loud noises, but our gate was high and we couldn’t see anything,” said Kaniz Sughra, Jan’s wife, who happened to be standing in the building’s garage at the very moment that her husband was being forcibly picked up from the other side of the gate.

The men left in several vehicles, including at least one double cabin white truck with police lights on its roof. An ambulance followed the convoy.

Jan has been attacked twice before. In one incident, he was driving with his son when someone hurled a brick at the windscreen of his car.

“We reported that to the police. It was investigated. In the end police said they knew who was behind it, but they could not tell us,” Sughra said.

She said her husband had received threats recently but told her not to worry about them.

Jan’s brother, Shahid Akbar Abbasi, also received a call from someone claiming to be a fan of his brother and asking for his phone number.

“My hunch is that they confirmed that I was not with my brother and that the number I gave them was still being used by my brother,” Abbasi said.

The reaction to Jan’s alleged abduction was swift. Pakistan’s opposition parties walked out of a session of parliament in protest, as did the journalists covering the proceedings.

The leader of the opposition in parliament, Shehbaz Sharif, condemned Jan’s disappearance on Twitter, adding: “The government's campaign to muzzle the media & critical voices is simply shameful. If something happens to Matiullah, PM will be held responsible.”

Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, son of slain Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto and leader of one of the main opposition parties, Pakistan People’s Party, tweeted: “Extremely concerned at news that @Matiullahjan919 has been abducted from Islamabad. The selected government must immediately insure his safe return. This is not only an attack on media freedoms & democracy but on all of us. Today it is Matiuallah, tomorrow it could be you or I.”

Within hours of the news breaking, #BringBackMatiullah racked up more than 100,000 tweets and started trending on Twitter in Pakistan.

Journalists and human rights bodies issued statements condemning the alleged abduction.

The Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists issued a statement threatening countrywide protests if Jan was not “released” within 24 hours.

“This has become a norm in the country to suppress voices of dissent for controlling media, imposing censorship and denying freedom of speech and expression in the country,” the statement said.

The press association representing journalists covering the nation’s Supreme Court urged the chief justice to take note of the incident.

The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, an independent body, also demanded Jan’s “release.”

“We are deeply concerned at increasing attempts to control the media, suppress independent voices, and curb political dissent, thereby creating an environment of constant fear,” the HRCP statement read.

Amnesty International for South Asia tweeted: “We are extremely concerned for the fate and wellbeing of @matiullahjan919. He has been the subject of physical attacks and harassment for his journalism. The authorities must establish his whereabouts immediately. #ReleaseMatiullah”

Pakistan’s information minister, Shibli Faraz, said the government had taken note of the abduction and was investigating.

“Unacceptable abduction of @Matiullahjan919 from Islamabad today, have spoken with IG @ICT_Police and instructed for immediate action for retrieval and registration of FIR,” tweeted Shahzad Akbar, a special assistant to the prime minister, Imran Khan.

Cases of enforced disappearance are widely documented in Pakistan. Journalists and human rights bodies have repeatedly investigated such incidents and often found the country’s intelligence agencies involved, especially when it comes to critics of the military or members of nationalist groups.

“The scourge of enforced disappearances continued unchecked across the country in 2018. Political activists, students, human rights defenders, lawyers, journalists, members of religious groups, and various ethnic minorities have all fallen victim in recent years,” HRCP wrote in its latest annual State of Human Rights report.

The human rights committee of the country’s Senate took up the issue several years ago and issued seven recommendations that were endorsed unanimously by the entire chamber in 2016. None of those recommendations was ever implemented.

Farhatullah Babar, who was part of the Senate committee, said they had no doubt institutions of the state were involved in these disappearances.

Babar also said that regardless of which party was in power, political governments were “totally helpless in this issue. They cannot do anything,” he added.

The country’s official Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances claims to have recovered thousands of victims but has so far not filed cases against any responsible party.

In 2018, the chairman of the commission, Justice Javed Iqbal, told the Senate human rights committee that they have identified more than 150 security officials involved in the forced disappearance of people. No action, however, was ever reported against any individual or institution.

“The abductors know they’re so powerful and have impunity that they did not even care for the abduction to be in view of a CCTV camera,” tweeted activist Usama Khilji.