One year ago on August 5, Indian Kashmir was cut off from the world as the Indian government blocked telecoms and internet after revoking an article granting the region autonomy.

Internet curbs were partially lifted during the year, but the ramifications for Kashmiri news outlets and their audiences are still felt, with service periodically blocked during flare-ups of unrest.

A fresh curfew was announced this week, ahead of the revocation anniversary, and parts of the communications block were extended on July 29, with authorities citing the potential for a rise in “anti-national activities in coming weeks.”

Local journalists say the restrictions, coupled with a new media policy, make it difficult to report on breaking news, or gain access to information or government comment, and create an environment ripe for disinformation and rumors to spread.

The Indian government has defended its measures, saying they are needed to maintain order and prevent the spread of terrorism.

With a population of 12 million, Kashmir has long been the scene of tensions. India and Pakistan both claim rights to the region, with each controlling only some parts. In recent years it has been rocked by militant attacks, protests and clashes.

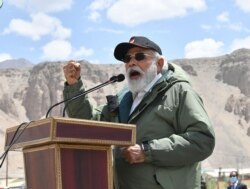

Until August last year, the Indian-controlled territory had autonomy. But that ended when Prime Minister Narendra Modi revoked Article 370 — which granted Jammu and Kashmir rights including its own constitution. In a televised address, Modi said, “Kashmir’s special status had been used by [Pakistan] as a weapon to incite people of the region against India.”

Around the same time, India sent a surge of troops to the region, cut off internet access, and detained thousands, including elected leaders.

‘Prevent any reporting’

The internet ban remained fully in place until March, when authorities allowed 2G access — a limited service that makes sharing messages and documents, or loading web pages, slow.

India said restrictions on high-speed internet were still needed to limit the spread of false news and thwart militants planning attacks.

Without full telecoms or internet service, however, journalists struggled to reach government officials for comment or to request interviews.

“The idea was to prevent any reporting from Kashmir,” said Safwat Zargar, a Srinagar-based reporter for the news website Scroll. He added that the restrictions prevented vital information from passing between the public and journalists.

Most journalists believe the restrictions were imposed to curb freedom of speech, Zargar said, adding, “I think the government also wanted to escape accountability and scrutiny from media for all the illegal detentions, curbs, using of force on protesters.”

Moazum Mohammad, vice president of the Kashmir Press Club, told VOA the communications restrictions have been the biggest hurdle for journalists. “It adversely impacted ground reporting. It also impacted livelihoods of journalists and left many jobless,” said Mohammad.

A drop in advertising revenue, both from regular business and government-allocated ads, made it hard for some websites to continue operations.

Idrees Kanth, an academic who focuses on Kashmiri contemporary history and politics, said the communication blocks served to “give the impression that everything is ‘normal’ in the Valley.”

The director of communications for Jammu and Kashmir and India’s embassy in Washington did not respond to VOA’s email requesting comment on how the restrictions impact local media.

Other journalists said the restrictions made it harder to access some locations or cover news as it happens.

“Our stories do not reach the people, who later feel that we have not covered the incident at all. It loses the relevance because by then rumors already dominate the discourse,” Rayan Naqash, an assistant editor at the multimedia news portal, The Kashmir Walla, told VOA.

He added that readers were not able to access verified information.

Mohammad Khalid, a local resident who follows current events, agreed and said it is hard to access news websites.

While Kashmir has newspapers, limited copies have been printed during the coronavirus pandemic. The population largely prefers online or TV news.

Security leaks

With limited internet access, journalists resorted to Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) and phone messaging apps such as WhatsApp and IMO, to send and receive information, but in some cases that exposed them to security and privacy vulnerabilities.

Last month, vpnMentor, a research team that tests VPNs, found that servers used with several apps favored by Kashmiris during the blackout were not fully secure and that personal data including email addresses, internet protocol (IP) addresses and device information were accessible.

Journalists previously said they work under the assumption that their communications are monitored, the media watchdog Reporters Without Borders reported.

In the past year, members of the press have also faced arrest, often on accusations of sedition or false news. Police detained several journalists since the lockdown, most recently Qazi Shibli, editor of news website The Kashmiriyat, who was arrested July 31 on suspicion of breaching security for keeping the peace. Shibli was previously detained for nine months, following an arrest in July 2019.

“Kashmiri journalists and reporters are repeatedly intimidated and even harassed,” the academic, Kanth, said.

A media policy that went into effect in May could further legitimize harassment of the press. “This policy actually puts in place a mechanism which legitimizes penal action from the government toward journalists who don’t toe the line,” Zargar said.

Reporters say the policy has the potential to scuttle journalism by defining what constitutes news and risks silencing the Kashmir press if the media self-censor for fear of reprimand.

“The media policy seems to be designed to engineer a spiral of silence. This policy is also a formalization of practices that were already in place and attempts to replace editorial boards with bureaucratic control over news,” said Naqash.