U.S. lawmakers and rights groups welcomed the release Wednesday of four journalists and media workers in Ethiopia’s Tigray region, and highlighted the important role the press plays in covering unrest.

The BBC confirmed the release of Girmay Gebru, a reporter for its language service, who was detained Monday, and said it was “seeking a full explanation.”

Translators with the French news agency Agence France-Presse (AFP) and Britain's Financial Times and a journalist working with The New York Times were also released, Abebe Gebrehiwot Yihdego, deputy head of Tigray's interim administration, told Reuters.

U.S. Representative Michael McCaul, the top Republican on the House Foreign Affairs Committee, described their release as “a positive development,” but told VOA the arrests “never should have happened in the first place.”

“There must be full access to journalists and independent investigators to look into these disturbing reports,” said McCaul, of Texas.

Gimray previously worked for VOA’s Horn of Africa service before joining the British broadcaster, where he filed stories in the Amharic and Tigrigna language.

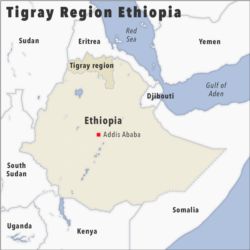

The BBC journalist, Fitsum Berhane of AFP, and Alula Akalu of the Financial Times were all arrested in Mekelle, the capital of Ethiopia’s Tigray region.

In an interview with AFP, Fitsum said soldiers burst into his home about 1 a.m. Saturday and threatened him, with one holding a gun to his head. The journalist said they accused him of supporting the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) and having an unregistered satellite phone. “I denied all because I don't know what they are talking about,” he said.

The AFP and Financial Times said earlier this week that the Ethiopian government had given them permission to report in Tigray, an area that has recently been closed off to international journalists.

The region has experienced unrest since fighting broke out in November between the national government and the TPLF, a political party that once dominated Ethiopia’s ruling coalition until Prime Minister Abiy Amhed came to power in 2018.

In a Wednesday statement, the Ethiopian prime minister's office said it welcomed media coverage in Tigray but said journalists were “bound by operating protocols” and that anyone found to “breach national laws” would be held accountable.

The office had previously announced that several international outlets were given permission to report in the region.

The BBC, Financial Times, The New York Times and AFP were among the outlets it listed.

The earlier statement added that allegations of media being denied access to the region were “a false representation.”

Silencing journalists

The journalists’ arrests led to widespread criticism from media rights groups.

The Foreign Press Association, Africa described it as “unwarranted and an open act of intimidation and coercion designed to impose self-censorship and prevent journalists from reporting the conflict in Tigray with an objective and non-partisan lens.”

And the Vienna-based International Press Institute warned of an “escalation in pressure on journalists in relation to the Tigray conflict.”

“Both local and foreign press must be able to report on developments in the region freely and without interference,” the IPI said in a statement.

Ethiopia’s Embassy in Washington, D.C., did not respond to VOA’s email and a telephone call requesting comment.

Journalists have come under pressure since fighting broke out in Tigray, with several reporters detained, questioned or attacked because of their coverage.

At least six reporters were arrested in November, in a move that Ravi Prasad, director of Advocacy at IPI, described as “a flagrant attempt by the Ethiopian government to prevent the media from reporting about the conflict.”

And last month, freelance journalist Lucy Kassa was attacked in her Addis Ababa home by a group of men who asked if she had connections to the TPLF and took photographic evidence she was using in her reporting.

The journalist told VOA at the time she believed the attack might have been related to her reporting for the international media. She had recently published a story in the Los Angeles Times about gang rapes allegedly carried out by Eritrean soldiers in Tigray.

A spokesperson for Ethiopia's Ministry of Foreign Affairs said earlier this year that the ministry was aware of reports that Eritreans had entered the country but did not confirm it. The spokesperson denied that Ethiopia had solicited any outside support.

The U.S. House Foreign Affairs Committee is due to hold a hearing on the crisis in Ethiopia later this month.

McCaul has highlighted the important role journalists play in covering the reports of mass violence taking place in Tigray.

“For far too long, the government of Ethiopia and other armed actors have blocked access by journalists and independent monitors to investigate these chilling accounts,” he said in a statement last week.

The region has been affected by internet and phone shutdowns since November, according to Amnesty International. The restrictions have prevented journalists from freely and fully covering the unrest.

“The scarcity of independent reporting coming out of Tigray during this conflict was already deeply alarming,” Muthoki Mumo, the Committee to Protect Journalists’ sub-Saharan Africa representative, said in a statement.

The recent arrests, Mumo said, “will undoubtedly lead to fear and self-censorship.”

VOA's Jessica Blatt contributed to this report. Some information is from AFP and Reuters.