In an election year, the investigation of a potential presidential candidate is a big story. But journalists, including some covering the house arrest of Nicaraguan journalist Cristiana Chamorro, have found themselves being questioned by authorities.

Since May 25, at least 21 journalists have been summoned by the Nicaraguan prosecution office and asked about their connection to Chamorro’s freedom of expression organization, Violeta Barrios de Chamorro Foundation for Reconciliation and Democracy.

Prosecutors have asked the reporters if they received training from the organization, read from articles the journalists had written, and warned them they may have violated laws.

At least one of those summoned — Univision freelancer María Lilly Delgado — is under investigation. Delgado told the Committee to Protect Journalists that Nicaraguan prosecutors would not question her while her lawyer was present.

Chamorro is under house arrest on accusations of money laundering, “abusive management” and “ideological falsehood.” Her foundation announced in February it would suspend its work because of a new law on foreign funding.

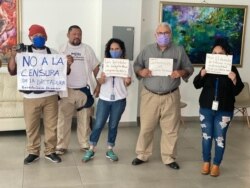

The summoning of journalists illustrates the tricky path for Nicaragua’s media, who already have to contend with online harassment, accusations of false news, attacks and detainment.

Journalists who spoke with VOA’s Spanish service on condition of anonymity say many have been silenced or self-censored from fear of reprisal by President Daniel Ortega’s administration, which has introduced new laws that affect media.

As Ortega campaigns for a fourth term in office, with elections scheduled for November, journalists and rights groups say the pressure is ramping up against the media and the opposition.

Authorities have so far detained six opposition presidential contenders.

One of those is publisher-turned-presidential candidate Miguel Mora, who was arrested for a second time on June 20.

Mora, who founded the cable news channel 100% Noticias, is under investigation for the same crimes as the other candidates — allegedly violating the Act to Defend the Rights of the People to Independence, Sovereignty, and Self-Determination for Peace.

He denies the charge, and his wife has been unable to communicate with him since his arrest.

"Months before the elections, we are seeing how all the political rights of the population are being violated. Freedom of expression, the right to association, and also the right to defend human rights is curtailed. We believe that the course of the elections will be plagued with human rights violations,” Astrid Valencia, the Central America researcher at Amnesty International, told VOA.

Ortega, who first came to power in 1979 but was defeated in 1990 by Violeta Chamorro, mother of Cristiana Chamorro, has defended the Nicaraguan prosecution office and the detentions. He said Nicaragua has the right to protect itself from outside interference, established in Article 1 of Law 1055, popularly known as the Sovereignty Law.

Ortega returned to office after winning the 2006 election as leader of the Sandinista National Liberation Front and has remained in power after making changes to the constitution.

Rise in repression

The recent arrests and arbitrary detentions appear to be part of a strategy to remove political opposition and silence dissent, Human Rights Watch said in a report released in June.

The harassment of opposition voices is being watched with alarm by the Inter-American Press Association (IAPA), which represents media owners in the region.

IAPA President Jorge Canahuati Larach said the international community must raise its voice in defense of the Nicaraguan people and their rights to freedom of expression and a free press.

“We must raise the conscience of the international community,” Canahuati said. “I believe people are suffering and that the government does not represent the will of the people, so it is important to create that space of freedom so that the people can express themselves.”

Restrictions have always been in place for independent journalism in Nicaragua, but the political crisis and the pandemic had made things worse, said Canahuati, who is president of Grupo Opsa, which publishes La Prensa, El Heraldo and Diario Diez.

“The government of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo is not willing to have any type of opposition and want to control the press. Journalists are in (their) sights after the detention of some political leaders from the opposition,” Canahuati said.

The media owner said Nicaragua has always been a challenging environment for independent journalists, “But the aggressiveness and virulence that is being seen, particularly in recent weeks, is a level that had not been seen before, and we should not be surprised.”

Carlos Quesada, founder and executive director of the International Institute on Race, Equality and Human Rights, said repressive media conditions in Nicaragua date back to 2018.

In April of that year, opposition to pension reform erupted into protests by thousands of Nicaraguans. Journalists covering the unrest were attacked and arrested, including Mora, who was detained for six months.

Legal threats

Quesada said it is becoming more difficult to resist the repression because the Sandinista government has passed laws making it easier to persecute opponents and journalists.

“Laws created in the past two years are designed to "criminalize human rights activists and defenders," and one of the targets is the press, he said.

Under the foreign agent law passed in late 2020, Nicaraguans who work for a foreign-owned organization or foundation must register with the Ministry of the Interior. Some exceptions apply, including international news outlets with correspondents in the country.

Under these laws, journalists can be accused of violating the sovereignty of the country if they receive support from an international organization, Quesada said.

"What it basically does is criminalize journalists," Quesada said. "There is no logical reason for these latest arrests, but the ultimate goal is to silence the voices of those who are critical of the government."

The laws appear to be having their intended effect. VOA attempted to reach several journalists for this article, but the requests were declined. Reporters said they feared for their safety.

Valencia of Amnesty International said the harassment that began in April 2018 has reached a crescendo as presidential elections approach.

She believes the recent court cases and summons are meant to intimidate the press.

Journalists are still reporting, despite the repression, she said, adding that “they are the ones who, until today, highlight credible voices so that the world can know what is happening in (Nicaragua).”

This story originated in VOA's Spanish language service.